The return of heritage fruit and veg varieties

- Published

There are signs that near-extinct varieties of fruit and veg, so-called "heritage crops" are making a comeback.

Cast into the sea by an 18th Century shipwreck, the legend goes that the Brighstone bean was washed up on to the shores of the Isle of Wight and saved for posterity.

Now it is one of hundreds of almost-extinct crops that have moved out of the history books and back into vegetable patches, gardens and orchards.

Purple-mottled and relatively small, the Brighstone bean does not immediately live up to the folklore.

But it was carefully nurtured by generations of gardeners on the Isle of Wight because of its history, rarity and distinctive taste.

Traditional types of fruit and vegetable have been forced to the margins in recent decades by EU rules and commercial agriculture.

Now the law and consumer attitudes are changing. Open-pollinated and passed down through the generations, "heritage" or "heirloom" crops such as the Brighstone bean are making a comeback.

"It results from the fact that people want to grow a variety of flavours that are good for the garden," says Chris Smith, co-owner of Pennard Plants, which specialises in heritage vegetable seeds.

"They're remembering what their grandparents grew and they want to do the same."

Historically thousands of different fruit and vegetable varieties were grown on a small scale for people who lived off the land.

"Many varieties up until the 1920s, maybe later, were bred for gardeners rather than for growing 20 acres of it... we're going back to a time when most people grew their own food and that's when most of the varieties were developed," says Chris Smith.

"A variety that is going for 300 years must have something going for it mustn't it?"

With the shift towards large-scale agriculture, intensive farming focused on a small number of crop varieties.

In addition, rules introduced by the EU in the 1970s restricted the trade of seed that had not been through an expensive registration process.

The result was that thousands of heritage varieties became extinct while many others significantly declined.

But the outlook for heritage varieties has changed.

How to garden using heritage techniques

Last year EU laws surrounding non-commercial seed were relaxed to make the registration process more affordable. Many said the reforms did not go far enough and French seed company Kokopelli recently entered a legal battle over the laws.

Earlier this year, the German advocate general of the EU courts, Juliane Kokott, said EU rules governing seed trade breach a range of principles, external surrounding free enterprise.

"There is a likelihood that the regulation will become (even more) relaxed," says Bob Sherman, director of Garden Organic, a vegetable conservation charity.

Champions of heritage varieties have reported renewed interest in old-fashioned seed varieties, driven by the recent trend for sustainability and home-grown vegetables.

But they say it is also because many of the crops just taste better.

Sweetcorn Ashworth was named after Fred Ashworth, a farmer who lived in New York State in the 1920s

Romanesco is an Italian variety cauliflower which tastes like a cross between cauliflower and broccoli

Ornamental squash such as (l-r) Muscade de Provence, table queen, Turk's turban, spaghetti, blue ballet, and pink banana are becoming popular

Smith recommends a tomato variety called the Black Russian.

Whereas mainstream varieties are bred with a thick skin to protect them in transit on their way to the supermarket, this traditional variety has a very thin skin, from an era when crops were eaten straight from the garden.

Claims about long-lost flavours are receiving growing support.

"New varieties are often developments and/or crosses of older varieties, bred for greater reliability and resistance to disease. Flavour is often lost in that process," explains Mark Diacono, food writer and gardener.

But the fascination with heritage crops also extends to their history, says Toby Musgrave, author of Heritage Fruit and Vegetables.

"It takes it beyond being just a fruit or vegetable. It becomes an object with a story."

The trail of tears bean, a small, rich-flavoured variety, got its name from Cherokee Indians, who took the bean with them when they were displaced by American settlers in 1838.

The bean is now an heirloom passed down through the generations and safe-guarded by Garden Organic in the UK.

The crimson-flowered broad bean also has a fascinating survival story, says Bob Sherman.

"It's a bean known for its beautiful deep crimson flowers… and the red colour of the flower is the result of a recessive gene… so in order to preserve it, it has to be kept absolutely pure."

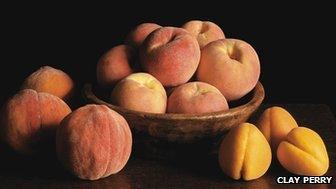

The peregrine peach (in bowl) arrived in the UK in 1906 and was traditionally "trailed" up the wall of a glasshouse

The bean, which dates back to 1778, faced near extinction in the 1970s, when Rhoda Cutbush in Kent donated her last few remaining seeds to Garden Organic for conservation.

But the biggest contribution of these historical varieties may actually lie in the genetic variety they have to offer in the future.

As controlled pollination has increased and farmers have concentrated on producing few select varieties, the gene pool in general circulation has shrunk.

"It is essential that we preserve the varieties and cultivars because we may well need them if one of these big commercial varieties fails," explains Musgrave. "There is the responsibility to maintain the genetic diversity."

- Published10 January 2012

- Published12 March 2012

- Published4 February 2011

- Published19 May 2010