Could France learn to love British beef?

- Published

France is famous for its gastronomy, while poking fun at British food is a Gallic pastime. There was also no love lost between French and British farmers in the wake of the BSE crisis. So why is a top Paris butcher now lauding British beef?

In a converted cellar, a man with unruly hair, seven-day stubble and a bloodied apron is cutting up meat.

The ease with which the knife cuts the thick steaks is impressive. And the white marbling of fat is not what you're used to seeing. Not in France anyway.

The man is Yves-Marie Le Bourdonnec, butcher to the stars.

The place is the meat lab and hanging room he's set up beneath a trendy new 24-hour steakhouse called Le Beef Club.

The meat is Le Bourdonnec's trademark rib-eye steak, matured for a slightly worrying 60 days.

The Beef Club boasts the best beef in the world. And all of it comes from Britain. A daring business proposition in a country which still massively associates British beef with "mad cow disease".

British beef still has something of the air of a forbidden fruit in this country. It was France that banned it unilaterally and totally illegally for six years after the EU ban had come to an end.

In many restaurants, they still put up signs to reassure customers their beef comes from France, Argentina, Germany… anywhere really just so long as it isn't Angleterre.

But Le Bourdonnec says his compatriots have got it wrong.

This is a man whose culinary star is on the rise. He's been feted by the New York Times, which awarded him their best hamburger of the world prize, and has an entry in this year's Who's Who.

He even features in a nude and nearly-nude calendar, aided and abetted by some of his female customers.

Now he is using his celebrity to try and start a meat revolution in France.

In a book called L'Effet Boeuf - Beefed Up in English - he says the French must abandon their way of doing things and copy the British.

On mad cow disease, he points out that it affected cattle farmers in many countries, including France, and that dairy cattle were infected, not beef herds.

comparetouscuts_2_getty.jpg)

Le Bourdonnec, pictured in New York, demonstrates French cuts of meat

The "buy French" response to the crisis was disingenuous, he says. It didn't protect consumers, it protected French cattle breeders' market share.

The reality, he says, is that Britain, which invented cattle breeding in the 1700s, still produces the best beef around.

"Your priority has always been getting the best result on the plate - the best taste, ours has been productivity… breeding the biggest animals in order to make as much money as possible," says Le Bourdonnec.

British breeds - Angus, Longhorn, Shorthorn, Galloway for example - are indeed much smaller than France's Limousin, Charolais or Blonde d'Aquitaine whose prize specimens weigh in at one and a half metric tonnes.

"In England, your breeders selected animals that are docile, small and fast-maturing that produce fatty meat. Because it's easier to make small, docile animals happy. Because when cattle mature fast there are less nerves in the meat and it is more tender."

People think lean beef is good but "more fat means the beef keeps for longer and can be matured longer," he says. "It's the fat that gives the taste."

In reality, the French, he says, hardly raise any cattle for beef at all. Almost half of what is sold as beef comes from cows raised for their milk - the rest from cows raised to have veal calves. The French word "boeuf" means the male of the species but almost none of the beef sold in this country is "boeuf" at all, it's "vache".

This talk earned Le Bourdonnec a rowdy reception from French breeders when he visited Paris's annual agricultural fair in February.

The Federation Nationale Bovine, France's biggest cattle breeders' union, while declining to put anyone forward for interview, agreed to comment on some of Le Bourdonnec's claims.

"France has four million cattle," says an FNB spokesman who wished to remain anonymous, "a third of all cattle in the EU. They produce some four million veal calves a year. But just because they are producing a lot of good veal, it doesn't mean they are not producing good meat."

Determining which breeds were best for beef was a matter of taste, he says. Even dairy cows could produce good beef if fed and looked after properly.

On the question of feed, Le Bourdonnec says one of the reasons British beef is better is that British animals are fed on grass all year round. France's beef cattle are mostly situated in the dry south-west of the country and so they eat a lot more cereal and maize.

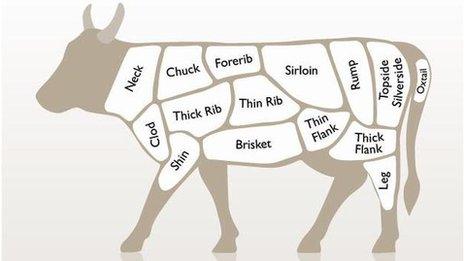

Simply the best? British cuts of beef

But "there is no proof that cattle fed more grain produce inferior meat to those fed on grass," says the FNB.

Perhaps as revealing as the FNB's answers was the tone in which they were delivered: a tone of amused detachment.

The idea that British beef might be better than France's own was simply funny.

The awfulness of British cuisine is an enduring French national joke, however unjustified that image has become.

There are few French families who don't have stories to tell about, for example, the things little Jacques was given to eat while staying with his pen-pal's family in Weymouth - about lamb with mint sauce and puddings that wobble.

The French nickname for the British may be "rosbif" (roast beef), but France's new celebrity butcher still has plenty of convincing to do.