Who, what, why: Why is hazing so common?

- Published

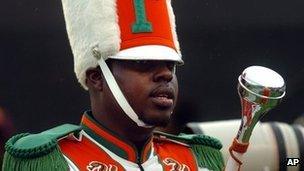

Membership of the Marching 100 is highly coveted at Florida A&M University

In November 2011, 26-year-old Robert Champion died from injuries he sustained in a beating. At least one person dies in the US as a result of hazing each year. But why is it still so common?

The beating of Robert Champion was not done in anger or retaliation. It was not to make him feel excluded or to warn him away.

Instead it was considered a rite of passage, part of the induction rituals doled out to new members of the Florida A&M University marching band, the Marching 100.

Thirteen people involved in the abuse have been recently charged, most with hazing resulting in death, a third-degree felony.

By definition, hazing is the practice of putting someone in physical emotional distress. "There's no such thing as harmless hazing," says Elizabeth Allen, a professor of education at the University of Maine.

Aside from physical violence, it can include sexual coercion, forced alcohol consumption, or dangerous "pranks" like forcing people to eat vile food mixtures or consume large amounts of water.

Hank Nuwer, author of four books on hazing, says that in America from 1970 to 2012 there was at least one hazing death a year, and often more than one, with a total of 104 deaths.

Champion's story has an extreme end, but his experience is not unique: a study conducted by the University of Maine found that 55% of college students experienced some form of hazing.

"That includes fraternities, sororities, marching bands, varsity sports intramural sports and other on-campus clubs and groups," says Allen. It's found in the military, athletic clubs and even in some workplaces.

'Bonding and unity'

The problem is not uniquely American, says Eric Anderson, an American professor at the University of Winchester in the UK. He says he sees just as much hazing in the UK as in the US.

"When people have sacrificed together, when they've gone through something difficult or painful together, it improves their level of cohesion and commitment to the group."

The people doling out punishment and those being punished each view hazing as a grand tradition, and do not see the activities they are being asked to do as hazing.

"Their motivations are most often for good things. They say: 'We wanted to feel like we accomplished something, we wanted to promote group bonding and unity,'" says Allen, who runs a hazing research centre.

Students are told that the activities they are enduring are the same ones previous generations endured, and that surviving them makes the new students part of a storied history.

"You can see how students would want to participate in a tradition. This is what unites them and gives them an identity. It draws them in," she says.

In fact, research indicates that the more arduous and dangerous a group's initiation rituals are, the more members like the group.

But hazing also has as much to do with inertia as initiation. "Do not tell someone who's been hazed that they can't now haze the next generation," says Eric Anderson. "It's that sense of injustice that we didn't have it better so nor should they."

This attitude goes beyond the hallowed halls of academics - doctors, for instance, have complained about safety requirements that forced new residents to work fewer hours.

Fighting hazing is a tricky proposition for US college administrators, many of whom are considering anti-hazing laws.

"You have to have the law to show in good faith that you're taking it seriously, but that doesn't mean the laws are going to help, and in fact sometimes hinder," says Anderson, who notes that some restrictions can make hazing more secretive and those in need less likely to call help.

"The law can help send a message, it can help holding people accountable, it can help to educate people by having a law, but it's not enough," says Allen. "We need to help students learn how to intervene if they are a bystander. A big surprise of our research is that a lot of the hazing is happening in public spaces."

Experts agree that changing the overall culture around hazing is necessary. They say that those involved in the hazing and those who witness it all need to agree that the practice is wrong, and agree to speak up and stop any hazing activities they see. But changing the culture is also harder than it sounds.

"The differences are so nuanced between an African-American fraternity, an athletic team, the military, and workplace hazing. Each is a culture unto its own, and that's part of the problem," says Hank Nuwer, who runs a website that tracks hazing incidents.

The fastest way to end hazing, he says, is for those doing the hazing to suffer serious consequences or witness a horrible outcome. But the ever-changing nature of the university system makes that difficult.

"These kids are 18 or 19 years old in college now, so they don't remember that four years ago some girls died doing that," says Eric Anderson.

"Their institutional memory is really short."