Emerging economies rise to prominence

- Published

Ten years ago, the so-called developed world dominated the global economy but a family holiday in Kenya provides the opportunity to assess how much that balance of power is shifting.

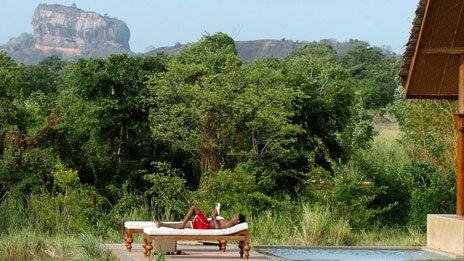

From Our Own Correspondent brings you insights from reporters in extreme locations. What you do not usually hear is a report composed in the comfort of a sun lounger, beside a sparkling pool in a tropical resort.

But I make no apology for admitting that that is precisely where this report was conceived. And yes, at times, I enjoyed a long, cool drink as I wrote.

Because the palm-fringed, white-sand beach of my Kenyan holiday hotel turned out to provide the perfect vantage point from which to observe one of the biggest stories of our time.

I had expected that the other holidaymakers would be - like us - middle-class Europeans enjoying a special treat. And two-thirds of the guests were just that.

What was intriguing was the other third.

At breakfast on the first morning there were two Chinese couples at the table next to ours. They turned out to be from Beijing and were taking a couple of days by the beach as part of an African safari trip.

That did not surprise me unduly because I have reported on the rise of Chinese tourism in Africa for the BBC and I know it is the fastest growing tourist sector on the continent.

But there were not just Chinese families at the hotel.

A couple of days later, there was a big wedding. The bride and groom were British, of Indian descent. At least half of the guests had flown in from the sub continent.

Add to that the parties of other Indian and Chinese guests, the Russians and the scattering of Kenyan families - escaping from Nairobi for some R and R (rest and recreation) on the beach - and it became apparent that a sizeable minority of the people staying at the hotel were from what economists would call "developing" or "emerging" economies.

Now the top elites even in emerging economies have always had enough money to shell out for a top-class hotel. But the people I was sharing my holiday with were not government ministers or tycoons. They were just ordinary middle-class people like me.

It began to dawn on me that my Mombasa hotel illustrated, in microcosm, a much larger process - quite possibly the most significant international economic development of all our lifetimes - the great levelling of the world economy.

The statistics show just how dramatic the progress of that process is. The International Monetary Fund is forecasting that next year the so-called developing world will out-produce the developed world for the first time.

What a turnaround. As recently as 10 years ago, the developed world still dominated the world economy, producing three-fifths of world GDP.

But let's be clear, this is not a product of the financial crisis.

The crisis accelerated the process - bringing many developed economies to a standstill - but it did not cause it.

Because this is not about the West going into decline - most developed economies are not shrinking - what is happening is the rest of the world is just getting richer a whole lot quicker.

The world is witnessing a rebalancing of wealth

And this vast rebalancing of wealth across the globe should not really come as a surprise. One day we made the effort to drag ourselves away from the various attractions on offer in the hotel to venture into town, into Mombasa.

This great East African metropolis was a cosmopolitan trading hub even while London was a regional backwater. Its ancient trading culture predates the rise of Europe and the West.

And you can still see its influence in the mosques and minarets, in the spice markets and in the faces of the so-called Swahili people - the Muslim descendants of marriages between local Africans and Arab traders and settlers.

The gap is closing between East and West

Indeed, standing in the centre of Mombasa, you realise that the rise of the developing world is really just a return to business as usual. After all, until the 18th Century, India and China were the richest countries on the planet.

The historic anomaly has been the incredible concentration of wealth in Europe and America that followed the industrial revolution. Economists call that chasm that opened up between East and West "the great divergence".

Well, looking around the pool of my hotel, I realised that what I was witnessing was nothing less than the growing momentum of a "great convergence" of the world economy.

It will be many, many years before average incomes in developing economies like China and India match those in the West - if they ever do.

But what was clear from that sun lounger in a Kenyan holiday hotel was that, for the middle classes at least, the world is rapidly becoming a much more equal place.

<bold>How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent</bold> <bold>:</bold>

<bold>BBC Radio 4: </bold>A 30-minute programme on Saturdays, 11:30 BST.

Second 30-minute programme on Thursdays, 11:00 BST (some weeks only).

<link> <caption>Listen online</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b006qjlq" platform="highweb"/> </link> or <link> <caption>download the podcast</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/podcasts/series/fooc" platform="highweb"/> </link>

<bold>BBC World Service: </bold>

Hear daily 10-minute editions Monday to Friday, repeated through the day, also available to <link> <caption>listen online</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p002vsng" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

Read more or <link> <caption>explore the archive</caption> <url href="http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/from_our_own_correspondent/archive/default.stm" platform="highweb"/> </link> at the <link> <caption>programme website</caption> <url href="http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/from_our_own_correspondent/default.stm" platform="highweb"/> </link> .