The Cold War rival to Eurovision

- Published

When nestled behind the Iron Curtain, the Soviet Union could not take part in the Eurovision Song Contest, so it set up a rival competition - and called it Intervision.

<italic>"The Soviet singer was so eager to win that she did a cartwheel up on stage. But her skirt fell down and she revealed everything to the judges. I'll never forget the face of the Soviet ambassador in the front row. We laughed like hell." - Jerzy Gruza, Polish director of Intervision Song Contest</italic>

During the Cold War, Europe was divided by a concrete wall and by rival ideologies. East and West competed in everything.

The Western allies had Nato; the Eastern bloc had the Warsaw Pact.

The West had the Common Market; the East had Comecon.

We had the Eurovision Song Contest; they had... the Intervision Song Contest.

The Soviet Union could not take part in Eurovision. It was not a member of the European Broadcasting Union, the club of Western broadcasters that organised the show. But that did not mean that behind the Iron Curtain people did not want to wear sequins and sing their hearts out. Of course they did. So the communist world created its very own songfest.

Berlin Wall: The Cold War made concrete

Intervision was born in August 1961 - just one week after the appearance of that rather more sinister Cold War icon, the Berlin Wall. With the division of Europe now a physical reality, artists in the East shrugged their shoulders and decamped to the shipyards of Gdansk in Poland for a socialist sing-song.

It was not a Communist Party functionary, though, who had come up with the idea - it was a Polish pianist.

Wladyslaw Szpilman was a Jewish musician who had worked for Polish Radio before World War II. On 23 September 1939, as the Nazis pounded Warsaw from the ground and from the air, Szpilman was performing Chopin's Nocturne in C sharp minor live on air. It would be the last live music on Polish radio until the end of the war.

Decades later Szpilman would become famous as the hero of Roman Polanski's film, The Pianist; he had survived Nazi invasion, desperate conditions in the Warsaw Ghetto and arrest. His family had been put on a train and sent to the gas chambers. But Szpilman escaped from the railway station and spent the rest of the war in hiding. After an experience like that, arranging a song contest must have been a walk in the park.

It soon became clear, though, that a shipyard was not the ideal venue for Szpilman's song contest. In 1964 his musical extravaganza relocated up the coast to the Polish seaside resort of Sopot. A spectacular open-air amphitheatre, the Forest Opera, became the annual home of the Sopot Music Festival.

"Szpilman invited singers from all over world, not just from Eastern Europe," recalls Polish music journalist Maria Szablowska. "The original idea was for them all to sing Polish songs. The festival became very popular in the entire Eastern bloc."

Then, in the 1970s, the director of Polish Television decided to transform the Sopot Festival into something much bigger.

"He wanted to challenge Eurovision," Szablowska says. "He knew about Eurovision's popularity in the West. We in Poland never could watch it, but we knew about it because of the winning songs, like Waterloo or Puppet on a String. The Polish TV chief wanted to have an Eastern Eurovision and this contest became a tool of propaganda for Eastern countries."

In 1977, the competition was officially rebranded the Intervision Song Contest. Behind the name change lay an iron determination - to prove to the West that "anything you can sing, we can sing better".

Not that the Eastern bloc blindly copied the successful format of the Eurovision Song Contest; there were key differences. First of all, the country which won the Intervision Grand Prix was not dumped with the responsibility of hosting the following year's competition: the contest was always held in Poland. What a relief for TV chiefs from the other countries taking part: they never had to worry about footing the bill for an expensive outside broadcast.

At Eurovision, timings were normally very precise. Performers had three minutes to get through their song, then it was all change and on to the next entry. Intervision was less strict, but that could make life hard for the Polish TV director, Jerzy Gruza.

"One Czechoslovakian girl went on the stage and stayed on the stage 45 minutes singing. She was singing, singing and singing," Gruza recalls. "My job was to get her off the stage and I almost had a heart attack. In the end she got tired and walked off."

Sometimes Gruza had even bigger problems to deal with. Like the moment Russian singer Alla Pugacheva had something of a religious experience up on stage. The atheist bosses of Polish Television were not impressed.

"At the end of her performance Pugacheva made the sign of the cross. There was big applause. But the head of Polish Television took me aside and said, 'What a scandal - we're going to cut your pay.'"

Set in a sea-side resort, singers performed against the backdrop of a forest

Maryla Rodowicz represented Poland in the very first Intervision Song Contest, but she had taken part in the Sopot Festival before. In 1970, her microphone had broken in mid-song and she had burst into tears.

"At the time, there were rumours that one of my competitors had chewed through the microphone cable," says Rodowicz.

She turned up at Intervision with a big bass drum and cymbals fixed to her back. She sang about feathered cockerels and wooden butterflies, of candy floss and rocking horses. Rather bizarrely, her backing singers stood there sharpening knives (perhaps in case anyone tried cutting through the microphone cable again).

Maryla Rodowicz: A win meant she gained a Porsche but lost her backing singers

Meanwhile a man in a dinner jacket was holding a big stick with a bird cage on top. Towards the end of her song, he opened the cage and released a dozen doves into the night sky. It was a theatrical number, which would not have looked out of place at Eurovision. Sadly Rodowicz did not impress the judges. But she did win the audience appreciation prize.

"I was presented with 40 roses," she recalls with a chuckle. "And that's not all. I also won a small Fiat. That night, though, they only gave me the car key, not the car."

It took Rodowicz weeks before she finally received her little Fiat. But she had no intention of holding on to it.

"My two backing singers told me I had to sell the car and split the cash between the three of us. I did sell the Fiat. But I didn't give them any of the money. My dream was to own a Porsche 911. A famous pianist friend of mine happened to be selling his old Porsche. So I borrowed some extra money and bought it from him. I'd got my dream car, but I lost my backing singers - they walked out on me."

The Soviet singer Roza Rymbaeva also won a prize at the 1977 Intervision. No flowers or car. Just a decanter and six glasses, courtesy of the Baltic Shipping Company.

She was just 19 when the USSR selected her for the competition. Speaking by phone from her native Kazakhstan, she admits to having been extremely nervous.

"That was my first ever trip to Europe. It was a huge responsibility representing such a giant country as the USSR. To return home without a prize would have been very unpleasant."

Participation in Intervision was not limited to the Soviet Union and its satellite states. In a bid to outdo Eurovision and establish itself as the world's premier music festival, the communist competition was open to artists from all over the world. Cuba was a regular.

Curiously, so was Finland.

Perhaps it was the Finns' frustration at always failing in Eurovision which prompted them to look East in search of a song contest they might stand half a chance of winning. Or maybe it was because of their determination to remain strictly neutral in the Cold War that they felt duty bound to participate in both Intervision and Eurovision.

Whatever the reason, at the 1980 Intervision, Finland entered one of its biggest stars. Marion Rung had represented Finland in the 1962 Eurovision Song Contest with the merry little number Tipi-tii (seventh place). She was back again in 1973 with Tom Tom Tom (sixth place).

At Intervision, Rung sang the moving ballad Where is the Love? (a question which may well have been directed at the juries dishing out the points at Eurovision). The international jury in Sopot loved her and she stormed to victory.

"At that time, Intervision was a much bigger festival than the Eurovision Song Contest," Rung tells me by phone from Finland. "I think the artists there were even better in some way. Because today I have the feeling that in the Eurovision it's not very important to know how to sing."

"My winning song, Where is the Love? is one of the biggest hits I've ever had. People still ask for it and I still sing it from my heart. This song means a lot to me because winning the contest gave a big boost to my career."

How many Eurovision winners can claim that?

As well as sharing Finland as a contestant, another thing the two competing song contests had in common was a swirling undercurrent of politics. Eurovision has often accused of being more about playing politics than pop music. And things were not much better the other side of the Iron Curtain.

Take 1971.

That year, the nearest thing the Soviet Union had to Cliff Richard, Lev Leshchenko, had spent months preparing for the Sopot International Song Festival. The Union of Composers of the USSR had chosen him to represent the motherland with the oddly-titled song, Ballad About Colours. But one week before the competition, Leshchenko was summoned to the Soviet Culture Ministry.

"The deputy culture minister told me there'd been a change of plan and that I wasn't going," he remembers. "They said the Polish organisers of the contest had secretly promised to help the USSR win the top prize. And that the last-minute advice of our Polish comrades was to send a female singer, not a male artist."

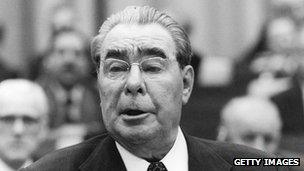

Was Soviet leader Leonid Brehznev behind plans to get singer Maria Kodryanu into the contest?

With just a few days to go before the competition, the Moldavian singer Maria Kodryanu replaced a livid Leshchenko. Only later would the real reason for the switch be revealed.

Before becoming general secretary of the Soviet Communist Party, Leonid Brezhnev had been local party chief in the southern Soviet republic of Moldavia. It's thought that the surprise decision to send a Moldavian singer to Sopot came either from Brezhnev himself or from his closest aides trying to please the boss. It's like David Cameron intervening to make sure the UK's Eurovision entrant comes from his Witney constituency.

Whoever took the decision, it was a disastrous one - both musically and politically. According to the Russian newspaper Kommersant, Kodryanu was totally unprepared for the contest and needed extra rehearsal time in Sopot to learn the song. That meant less rehearsal time for other countries, including Czechoslovakia and Hungary, sparking rumblings of discontent from across the Eastern bloc.

In his post-contest report, the Soviet consular general in Gdansk, Comrade Borisov, wrote: "The Czechoslovakian and Hungarian delegations expressed their anger at the situation. One of the Czechs made a number of anti-Soviet comments, accusing the Soviet delegation of behaving as if this was their country and of breaking all the rules."

Kodryanu tried her best, but it was not to be. In the main competition, the USSR came an embarrassing fourth. Moscow never liked to admit it was wrong about anything. But the Soviets knew they had messed up.

The following year, Leshchenko was rehabilitated and dispatched to Sopot, where he won the top prize (something the British Cliff Richard himself never managed to do in his two Eurovision appearances). Soviet pride had thus been restored.

Judging by the negative reception that the audience in Sopot gave some Soviet artists, Poland clearly did not enjoy being the USSR's puppet on a string.

"Sometimes even good artists from the Soviet Union were not appreciated and got whistled at by the spectators," recalls Eugeniusz Terlecki, general director of the Baltic Artistic Agency, which helped organise the contest. "Russian people as a nation are fine. But the Soviet Union as a country and as a government did a lot of bad things and we remember that."

Even the presenter of the Intervision Song Contest, Jacek Bromski, took every opportunity to poke fun at Moscow.

"Of course, I knew the rules," says Bromski. "I couldn't say, 'I hate Stalin, Lenin and the rest of you communist pigs,' because they would probably put me in jail. But it didn't prevent me from saying something between the lines, because that gave you a lot of applause from the public.

"For example, we were collecting votes like they do at Eurovision. I was calling every capital and asking for their results. One year when I was calling Moscow, there was no answer. So I said, 'Moscow, Moscow - wake up!' Then I had very big applause from the audience. 'Moscow, are you sleeping? Wake up!' Everyone was laughing. In the end I said, 'Better let them sleep.' That bit was cut out afterwards."

For millions of viewers in the Soviet bloc, it was not the song contest itself that had them glued to their TV screens; it was the interval acts. Big names from the West made special guest appearances in Sopot among them, Gloria Gaynor, Petula Clarke and Boney-M. This was a rare chance for music lovers in the East to get a taste of the West.

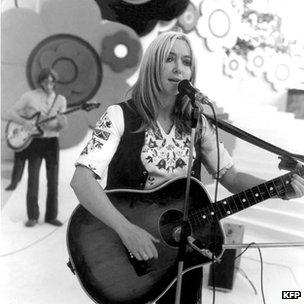

Gloria Gaynor was one of a handful of singers from the west to make an appearance at Sopot

"It was a window to a free world for us," says Szablowska. "It was like fresh air coming to us. Because suddenly, for these two or three evenings, we had Western stars, we had concerts in a very beautiful place and we felt free. It was fantastic."

Which is why Intervision became compulsive viewing across Eastern Europe. As a result, Bromski, the presenter, became a household name from Vladivostok to Varna. But he only realised that when he flew to Moscow to attend a film festival.

"The red carpet was set on Red Square and on this red carpet I saw Robert De Niro," Bromski recalls. "So I came up to him and got talking to him. Suddenly, from behind a rope, a young man came running to us with a notebook and pen, obviously going for an autograph. I stepped aside because I thought he was going to ask Robert De Niro for an autograph. But he said, 'Mr Bromski, Mr Bromski, can I have your autograph?' I didn't realise I was popular in Russia and that all Russia was watching the Intervision Song Contest."

Jerzy Gruza remembers life behind the scenes at Intervision

In the same way that communism liked to be seen as morally superior to capitalism, so Intervision laid claim to being more uplifting, more cultural and less commercial than the Eurovision Song Contest. Behind the scenes, though, morals sometimes took a back seat.

"One evening after rehearsals we had a late dinner in the Grand Hotel," contest director Gruza says. "On a stage in the restaurant there was a late night show for guests. A girl was dancing and making striptease. Then she took a torch with fire, made different movements and tried to put this torch in different parts of her body. At the end she put the torch between her legs. All of us sitting there were making such eyes. We were all paralysed."

But by the summer of 1980, a songfest was the last thing on the minds of the Intervision organisers.

At the Lenin shipyard in Gdansk, thousands of workers had gone on strike. Their industrial action was a direct challenge to the entire communist system, and it was the birthplace of the Solidarity movement. All of this was going on just a stone's throw from Sopot and the Intervision Song Contest.

"I think that the strike in the shipyards started because of Intervision, to get exposure," says Bromski. "They knew there were going to be a lot of international press there, a lot of foreign guests, so they started deliberately."

The song contest went ahead, but nerves were jangling.

"There was big tension," Gruza recalls. "I remember there was a big bang up on stage. A lamp had broken. Two minutes later the entire orchestra was sitting in the bus trying to escape. They were terrified by the sound of the bulb breaking. They thought it was a bomb, or the Resistance, or something.

Political foment was bubbling a mere stone's throw away from the Intervision contest

"That year, one of the Polish singers had a song called Our House is Burning," says Bromski. "I knew that the vice-president of Polish TV responsible for political affairs was at the contest. So I made a joke. I said to him, 'Do you think it's safe to have a song with the title Our House is Burning while we have strikes in the Gdansk shipyards? And later I noticed that they had changed the title of the song."

After 1980 there would be no more Intervision Song Contests. The following year, the Polish authorities declared martial law. There were tanks on the streets and clashes between protesters and riot police. When the competition returned a few years later, it had reverted to its old name: the Sopot Music Festival.

In the Cold War of crooning contests, Eurovision had emerged victorious. It was a sign of things to come. Not long after, the <link> <caption>Berlin Wall</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/places/berlin_wall" platform="highweb"/> </link> came crashing down and communism was consigned to history. Much of the Eastern bloc became part of a united Europe and of Eurovision.

But to those in the East who had at least tried to create an alternative to the Eurovision Song Contest, I say this.

Thank you for the music, the songs I'm still singing. And all the joy they're still bringing...