History of Cardenio: Is Shakespeare's lost work recovered?

- Published

'Lost' Shakespeare play performed for first time

After 20 years of work, an American Shakespeare scholar is bringing his restoration of what he says is a lost play by the Bard to the stage.

In 1613, royal records show payment was made to a Shakespearian actor, who starred in a play performed by Shakespeare's theatre company, written during Shakespeare's tenure as playwright.

In 1653, the play, The History of Cardenio, appeared in a register of soon-to-be published works. But Cardenio, credited in the register to Shakespeare and his collaborator John Fletcher, never appeared in print.

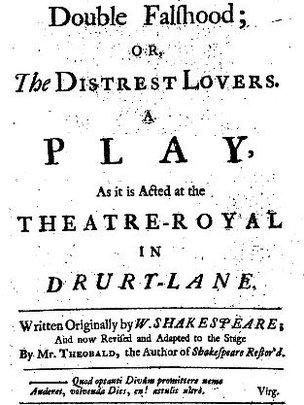

Seventy-four years after that, playwright, editor and Shakespeare imitator Lewis Theobald published a play called Double Falsehood - based, he said, on three original manuscripts of the History of Cardenio.

.jpg)

Gary Taylor (left) with the play's director, Terri Bourus

"Increasingly, with the availability of massive databases and more sophisticated attribution tests, the consensus is now that it's partly by Shakespeare and partly by Fletcher," says Gary Taylor, editor of the New Oxford Shakespeare.

"But the 18th century text we have is seriously messed with and modified."

For the past 20 years, Taylor, a professor of English at Florida State University, has been doing the long and difficult work of extracting Shakespeare's words from a surviving editon of Double Falsehood - using both computer programs and centuries-old documents to chip away anachronistic speech and modern conventions, and to recreate the script as closely as possible to what were Shakespeare's original intentions.

After decades of rewrites, readings and revisions, the Indiana University and Purdue University-Indianapolis (IUPUI) theatre department staged the first professional, full-scale production of the History or Cardenio, as resurrected by Taylor.

It's bold and brash and funny and moving. But is it Shakespeare?

Spanish influence

The play tells the stories of two sets of lovers - the earnest scholar Cardenio and his fiance, Lucinda, and Cardenio's friend Fernando and the mixed-raced shepherd girl Violenta.

The betrayals, forced marriages, missed connections and late-night seductions that appear in the play are familiar Shakespearean themes. But the story itself comes from Miguel de Cervantes, who tells the lovers' tale intermittently throughout his epic novel Don Quixote.

About a decade before Cardenio was first performed, King James I made peace with Spain, which led to an influx of Spanish art and culture into England, says James Shapiro, professor of English at Columbia University. The tale of Don Quixote was frequently mined by English artists and writers.

That there might be not just a missing Shakespeare play but one based on the works of Cervantes has made The History of Cardenio a topic of fascination for years.

"They were two of the greatest imaginative artists of this world, at that point," says Stephen Greenblatt, a professor of English at Harvard University. "They were living in divided world, but its at this moment those wires crossed."

<bold>'A</bold> <bold>rcheological exploration</bold> <bold>'</bold>

To try to recapture how Shakespeare and Fletcher interpreted the works of Cervantes, Taylor had to deconstruct the Double Falsehood manuscript, with some tasks being easier than others.

Sophisticated databases and text recognition software can detect lines that were likely to have been written by Shakespeare. A trained eye can sense those that came later.

"The first thing you have to do is identify what bits come from the 18th century and get rid of those," Taylor says, noting that phrases like "brutal violence" that appear in Double Falsehood were unlikely to have been used in Shakespearian times.

Then came the larger, more complicated task of evaluating entire scenes.

"We're talking about an archaeological exploration on the part of scholars who are trying to find remnants of that Shakespearian text," says Shapiro, author of Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare? "You have to dig down, and then you're relying on your ear. It gets subjective."

A rape scene in Double Falsehood raised red flags. "All of the dialogue that points to the rape is very 18th century, and that suggests that the play has been changed in a significant way," says Taylor.

"You can fit those pieces together, but you still have to fit together some blanks," he says. "To do that, I had to write material that either sounds like Shakespeare or like Fletcher."

Taylor's version of the rape scene depicts "what lawyers today would call coerced consent," he says: a hasty, pre-coital marriage vow that he says is more in keeping with 17th century mores.

Throughout the process, Taylor has done staged readings and smaller performances of the show, each time revising the script to better reflect Shakespeare's influence.

The show at IUPUI was the first entire performance from start to finish, with a professional cast and crew. After the performance, Shakespeare scholars from around the world gave notes and feedback for further improving the script.

"It's a very tricky effort, but he has recovered [some original work]," says Roger Chartier, director of the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales in Paris. "Like in the Sistine Chapel, where people are trying to find the the original painting, he makes us able to listen to some of the Shakespeare lines and some of the Fletcher lines."

Lingering doubts

Taylor's project, however, is predicated on the commonly-accepted belief that Double Falsehood was in some part written by Shakespeare.

Not everyone is convinced.

Tiffany Stern, a professor of early modern drama at Oxford University, argues that Theobald was both a noted Shakespeare imitator and an editor of Shakespeare. His edition of the Bard's Complete Works did not including Double Falsehood.

Double Falsehood as published in 1728

"When he's editing he tends to tell the truth. As a playwright, he's a bit of a liar," she says.

"You find what you look for," she says of the evidence pointing towards Shakespeare's writing in the Theobald play. "If you look for Shakespeare in the work of a famous imitator, you will find Shakespeare whether he's there or not."

Other scholars are more generous. Shakespeare's hand is in Double Falsehood, says James Shapiro, but challenges remain. "You have to take into account that you're dealing with an adaptation of an adaptation," he says of the Theobald script.

There is original work to be recovered - but much to be imagined.

"Gary is someone who knows the drama of the period as well as anyone," he says.

"This is an informed act of speculative recreation, but it's also a bit of creative writing on his part, and it has to be understood that way."

Evolving tradition

Unless an original manuscript is found, the complete recovery of The History of Cardenio is impossible.

The 2016 Oxford edition of Shakespeare's Complete Works, of which Taylor is the general editor, will contain fragments of the play identified as Shakespearian, but not the full drama as produced at IUPUI.

But the play, complete with Taylor's addition, will continue to evolve. Producers from New York have expressed interest, and Taylor's work continues.

That may be the most authentically Shakespearian aspect of the entire project.

"It was true in general of Shakespeare's practice. He's not interested in fidelity to his sources. He's interested in what will work on stage," says Greenblatt.

"That was the nature of Shakespeare's own relationship to Cervantes. It's not about direct lines of transmission.

"It's about mobility and divergences, re-imaginings and transformations."