Driverless cars and how they would change motoring

- Published

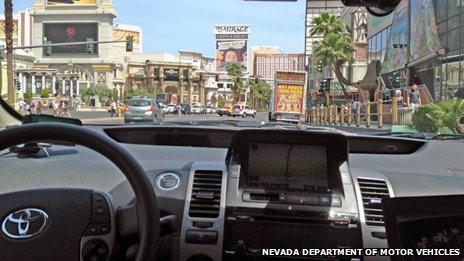

There are plenty of distractions in Las Vegas, but not for this driver

Nevada has licensed Google to test its prototype driverless car on public roads. Assuming the technology eventually becomes commercially viable, how would a car that drives itself change the way we drive - and what might stay the same?

After tests on the famous Las Vegas Strip, driverless cars will soon be a reality on the roads of Nevada.

The state has approved the US's first self-driven vehicle licence, meaning that a Toyota Prius modified by search firm Google will be the first to hit the highway.

So what would a world of driverless cars look like?

Safer roads

More than 1.2 million people across the world die every year in road crashes, and as many as 50 million more are injured, <link> <caption>according to the World Health Organization</caption> <url href="http://www.who.int/entity/roadsafety/decade_of_action/plan/en/index.html" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

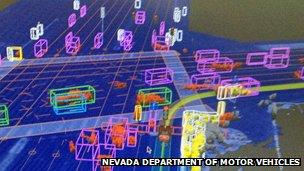

The cars - like that in Google's prototype - will process more information faster than a human driver

In the US, driver error - weaving out of the lane, drink driving and distracted driving, for example - is a factor in at least 60% of fatal crashes, according to <link> <caption>National Highway Traffic Safety Administration</caption> <url href="http://www-fars.nhtsa.dot.gov/People/PeopleDrivers.aspx" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

"Your automated car isn't sitting around getting distracted, making a phone call, looking at something it shouldn't be looking at or simply not keeping track of things," says Danny Sullivan, editor in chief of MarketingLand.com, who took a two-minute ride in Google's car on a closed course at a technology convention last year.

"It's not looking down to change the radio and looking up and noticing all the cars have stopped."

Google's car adheres strictly to the speed limit and follows the rules of the road, says Tom Jacobs, a spokesman for the Nevada Department of Motor Vehicles, who has also ridden in the Google car.

"When the car is on self-driving mode, it doesn't speed, it doesn't cut you off, it doesn't tailgate."

And in the future, autonomous cars will be able to communicate with one another, allowing them to negotiate lane changes and overtaking, analysts predict.

A more productive commute

"If you truly trust the intelligence of the vehicle, then you get in the vehicle and you do our work while you're travelling," says Lynne Irwin, an engineer and director of the Local Roads Program at Cornell University.

"That would stretch my day, it would make me more productive."

Fewer traffic jams...

Special licence tags identify self-driving cars

Traffic usually slows as the volume of cars on a road increases, because drivers slow their speed to accommodate the narrowed distance from the car ahead of them.

But autonomous vehicles, especially if they can communicate with each other, could in theory drive nearly bumper to bumper at high speed, says Irwin.

"You could get a lot more people moved at a higher speed on an existing road way," he says. "Congestion would be something you could tell your grandchildren about, once upon a time."

...but more cars

Americans have been driving less for a number of years, a trend that is <link> <caption>especially significant among young people</caption> <altText>BBC Magazine feature</altText> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-15847682" platform="highweb"/> </link> . But driverless cars could extend car ownership to some groups of people previously unable to own a car.

"You give people mobility who might not have mobility today," says Sven Beiker, executive director of the Center for Automotive Research at Stanford University.

"They can see the personal automobile as a service provider."

This includes elderly drivers who feel uncomfortable getting behind the wheel at night, whose eyesight has weakened or whose reaction time has slowed.

Also, people with epilepsy now unable or forbidden to drive could more easily get around, as could people with broken limbs, paralysis or other disabilities.

No more school run

Older children could take the car alone, potentially freeing suburban parents from chauffeuring drudgery.

A car could take the children to school early in the morning, then return home on its own to pick up the parents for their commute.

After a late-night carouse, a drinker could find and reserve a hire car on their phone, then have it pick them up and drive them home.

Car as personal train carriage

Many Americans already see adventure in long road trips.

They might schedule even lengthier journeys if they can relax and rest while the car keeps its eyes on the road.

Designs will change...

Google's car is a modified Toyota Prius, but expect the designs to take a new directions, says Irwin.

"When you get to a technological change, the first thing we do is we mimic what people are familiar with and comfortable with," he says.

"People like to look out the window so I suspect we'll keep windows in some shape, but maybe they don't need to be quite the way they are now. If cars aren't going to hit each other, maybe we don't need bumpers."

...but roads won't

Four million miles of roads criss-cross the US, and 50% of those are unpaved, says Irwin.

While national road design standards - lane and shoulder width, curvature radius, lines of sight and stopping distance - are constantly updated to account for changing driver habits and automotive innovations, the US simply has too much infrastructure already in place to revamp the system, he says.

And VIPs will still need human drivers

Whatever happens with the technology, President Obama won't give up his Secret Service driver

Driving a high-profile passenger demands a lot more than just keeping the car on the road from beginning to end, says Tony Scotti, a trainer of security drivers.

In addition to piloting the vehicle safely, security drivers must survey the road and the beginning and end points for potential hazards or security threats, be able to summon authorities and back-up, and know where the local hospital is, he says.

"A professional security driver knows the signs that things aren't good and can go to hell in a hand basket," he says. "I don't see that the car, computer or otherwise, could figure that out."

Also, he says, kidnapping insurance policies held by many high-level corporate executives require a trained security driver.

- Published8 May 2012