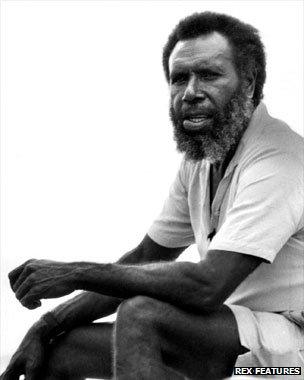

Eddie Mabo, the man who changed Australia

- Published

People gathered this week in Townsville, Queensland, to remember a seminal moment in the nation's history, and the efforts of one man to bring it about.

Aboriginal Australians are celebrating the 20th anniversary of their landmark victory over land rights.

It was on 3 June 1992 that the Australian High Court overturned more than 200 years of white domination of land ownership.

The victory was largely down to one indigenous man called Eddie Mabo.

That's why the legal decision is universally known as "Mabo".

But who was Eddie Mabo, why did he take up what must have seemed like a hopeless cause and what is the legacy of his campaign?

"Quite simply, Eddie Mabo brought an end to a two-centuries-old lie," says Rachel Perkins, director and inspiration behind the new movie, Mabo, released to coincide with the 20th anniversary of the historic High Court case.

"For two centuries, the British and then white Australians operated under a fallacy, that somehow Aboriginal people did not exist or have land rights before the first settlers arrived in 1788."

The "fallacy" that Perkins speaks of is the concept of Terra Nullius, land belonging to no-one. Concocted by the early settlers, it was used, systematically, cynically and effectively to deprive the indigenous people of their own land.

It was also a flagrant disregard of Britain's own existing laws, which stated that the Aboriginal people did have title rights over their own land.

Yet, the first colonialists decided, for commercial reasons, to ignore all that and peddle the view that Aboriginal people were primitive, disorganised, culture-less creatures who deserved no rights over land.

The assumptions were quite erroneous, of course, but Terra Nullius was set in unshakeable motion and stayed rooted in place for two hundred years, even though Aborigines had been in Australia for at least 40,000 years.

When the decision overturning Terra Nullius eventually came, the judges referred to the policy as "the darkest aspect of (our) national history" and one that left "a legacy of unutterable shame".

It would most likely still be in place had it not been for Eddie Koiki Mabo.

Mabo was a Torres Strait islander from Mer (Murray Island), off Australia's north-east coast.

Born in 1936, Mabo started life like so many other indigenous people, deprived of a meaningful education, denied access to whites-only buses, cinemas, even toilets. This was apartheid in Australia, not South Africa.

He married Bonita, his teenage sweetheart and with whom he had 10 children in a loving partnership that lasted 30 years.

Mabo ended up on the mainland working a number of jobs, including labouring on the railways.

It was during a stint as a gardener at the James Cook University at Townsville in Queensland, that his eyes were opened to the greatest injustice his people had ever been subjected to.

In 1974, he became involved in a discussion with two academics.

He told them of his dream of ending his days on Murray Island, on the ancestral land that had been handed down through his family for 15 generations.

The debate about Mabo's legacy still goes on today

According to accounts of the conversation, the two scholarly figures looked at each other and then, delicately, told Mabo that he didn't own the land and that it was Crown land.

Mabo expressed disbelief and shock. He's recorded as saying: "No way, it's not theirs, it's ours." But he was wrong.

He was another victim of Terra Nullius, like so many of his fellow indigenous people had been before him. Unlike them, however, Mabo wasn't going to accept it.

At 31, this affrontery became his epiphany. He immediately saw the injustice of it and from then on dedicated his life to reversing it.

"He became a driven man," says his friend and documentary maker, Trevor Graham. "Koiki was ambitious for himself and for his people."

Mabo gained an education, became an activist for black rights and worked with his community to make sure Aboriginal children had their own schools.

He also co-operated with members of the Communist Party, the only white political party to support Aboriginal campaigns at the time.

Mabo rejected the more militant direct action tactics of the land rights movement, seeing the most important goal as being to destroy the legal justification for what he regarded as land theft.

He petitioned, campaigned, cajoled and questioned Terra Nullius for 18 years.

Then, in June 1992, the years of sacrifice and persuasion came to fruition.

A panel of judges at the High Court ruled that Aboriginal people were the rightful custodians of the land.

The judges satisfied themselves that Aboriginal people had been in Australia first, did have a long, rich culture that denoted civilisation and had voluminous evidence of land demarcation, usage and inheritance, to back up their claims of longevity and history.

But it was a bittersweet moment for the indigenous population.

The man who had engineered the historic change of law, never lived to witness it himself. Mabo died five months earlier from cancer in January 1992, at the age of 55.

Later in 1992, Mabo was posthumously awarded the Australian Human Rights Medal. In 2008, a library at James Cook University was named after him.

Many indigenous Australians still live in poverty

Other forms of recognition have been added. But 20 years after the judgement, there's still a debate among constitutionalists, lawyers and politicians about the legacy of Mabo.

It clearly did not, for instance, lead to vast numbers of white Australians being forced from their homes, businesses, mines or farms.

Nor did the judges intend that it should. They ruled that the Mabo decision in no way challenges the legality of non-Aboriginal land tenure.

In fact, the court went to considerable lengths to establish that the impact of its judgment will be minimal on non-Aboriginal Australians.

Only land such as vacant crown land, national parks and some leased land, can be subject to claims by the Aboriginal owners.

So, in many ways, the victory has been more symbolic than practical.

But that hasn't stopped indigenous people, like Queensland elder Douglas Bon, taking great satisfaction in the ruling.

"It gave us back our pride. Until Mabo, we had been a forgotten people, even though we knew that we were in the right."

Others, mainly white opponents, regarded the judgement as a mistake.

The former president of Western Australia's Liberal Party, Bill Hassel, said the ruling was greeted with "outrage".

"The High Court, which is not elected by anybody, not accountable to anybody, had presumed to move into the legislative area to make a whole new law," he said.

Some went further, fuelling the hysteria with unsubstantiated claims - Jeff Kennett, then the premier of Victoria, said suburban backyards could be at risk of takeover by Aboriginal people.

Ten years later, he conceded his fears were unfounded.

"I think that like many others, I was trying to deal with something that was new, that was undefined," Kennett told The Age newspaper.

The practical effects of Mabo have, indeed, been mixed, judging by figures from the Koori Mail, a national indigenous-owned newspaper.

Up to April 2010, 84 native title cases had been dealt with by the courts, and 854,000 sq km (330,000 sq miles) is now covered by native title determinations.

But that's just 11% of Australia's land mass. In New South Wales, the most populous state, Aboriginal people have title over only 0.1% of the land.

Les Malezer, chairman of the Foundation for Aboriginal and Islander Research Action, is critical of the native title system for its failure to deliver for indigenous people.

"If Koiki Mabo were alive today he would be an angry man," says Malezer. "The rights he won in the High Court have been eroded away by government, courts and socio-economic pressure."

Others, while acknowledging the shortcomings of Mabo's long-term legacy, still regard it as a watershed moment in Australian political, cultural and economic life.

Rachel Perkins, director of the new film, says Mabo's is "an iconic story in the tradition of great Australian tales, how a man, his wife and his mates profoundly changed the nation".

That is the view most widely endorsed by history.

Eddie Mabo had challenged the very ideological establishment of Australia and the first Australians.

He had refused to surrender his interests, or those of his people, to the domination of others.

He was, if you like, an Australian Nelson Mandela, someone who led his people in a struggle against incalculable odds, to what was rightfully theirs.