Turning around lives of the homeless

- Published

A project helping homeless people in a Sydney suburb is claiming impressive results, by challenging the notion that people living on the streets need to find the help themselves.

Are we helpless when it comes to the homeless?

It seems that many countries and societies don't know how to solve this enduring problem.

But now, in Australia, which has 100,000 homeless people, an attempt to confront the issue with direct, quantifiable action appears to be yielding impressive results, for both the individuals and the state.

It all began in 2007, when a philanthropist approached Mission Australia with an idea.

Mission Australia is a 150-year-old Christian community organisation that assists those on the lower rungs of life, such as the poor and homeless and has the staff and expertise to take on big projects.

The philanthropist, who prefers anonymity to publicity, explained that her own parents had been homeless and that, with the considerable personal resources at her disposal, she wanted to give something back.

After discussions, the scheme came to be called the Michael Project, named in memory of her dead husband.

At her request, the aim was to design a brand new service and to change the lives of thousands of homeless men, permanently.

She would put up the money for what would become an expensive experiment in social readjustment.

These were, after all, people who had often given up on themselves and were largely being ignored by society.

Of the thousands of men who passed through the Michael Project, 253 entered the research study and 106 made it to 12 months.

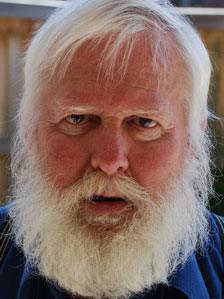

One of those was Gordon. He is 68 and has the kind of friendly, white-bearded, Santa Claus-type face that charms everyone who meets him.

But behind the jocular, engaging demeanour, Gordon's story reads like it's been lifted from the pages of the homeless person's stock-in-trade manual.

Gordon was an accountant with two practices and a beautiful home.

But 12 years ago, he lost everything, including his girlfriend, when mental health problems began to dog him.

Gordon has turned his life around

It left him devastated and homeless.

For the first two years "home" became a shipping container.

The adjacent river was his bathroom. He shared a field with a goat and a cow.

Gordon sank further into depression and was admitted to a series of psychiatric hospitals for a succession of well-meaning, but ultimately futile, therapies.

Then, four years ago, Gordon was introduced to Mission Australia and the Michael Project. It changed everything.

He now has a clean, one-bedroom apartment in Parramatta, west of Sydney, that he calls home.

There's a television, an audio system, a bookshelf that includes Shakespeare and pictures that he painted, including one of a 19th Century Mexican cowboy.

"That picture got me into art college when I was a young man," explains Gordon, with a nostalgic glint in his eye.

The apartment and all that's in it have been paid for by Gordon himself out of the disability allowance that's been organised for him.

"The project changed my life," he says. "It gave me back my confidence."

The Michael Project is about more than putting a roof over someone's head.

It is a wrap-around support service tailored to an individual's needs.

At its heart lies the one-to-one relationship between the homeless person and their mentor, or care worker.

In Gordon's case that's Claudia, a care worker with the kind of patient, understanding disposition usually associated with the most dedicated of hospice nurses.

Each case manager like Claudia has up to 20 clients but together, they systematically worked through each of Gordon's problems.

If he needed a dentist, Claudia would get him an appointment the same afternoon.

If he required a doctor's visit, one would be arranged for the following morning.

Job interviews, CVs, contact numbers, access to phones, advice on pensions, everything needed to help Gordon re-enter normal society was provided and, crucially, it would be provided immediately.

There would be no drift, no inertia, no "I'll do it tomorrow" attitude, which would only rack up the costs of fixing it later.

This would be a full-on, bespoke, intensive approach to break the cycle of aimlessness and hopelessness associated with long term homelessness.

The results of the whole scheme, since verified by outside auditors, have been remarkable.

Before Michael, there was practically nobody in long-term housing. After Michael, 50% were in permanent homes.

Sydney has thousands of homeless

Before, homeless people were four times more likely to need hospital care than the general public. After, that dropped to 1.7 times. Before, 6% were employed. Afterwards, that tripled to 18%.

Overall, the cost to taxpayers went down from $24,399 (£15,567) per homeless person, a year (in costs to the health, justice and other systems) to $20,798 (£13,270). That's a saving to the state of $3,601 (£2,298) for every homeless person.

"It's more expensive to have a person homeless than not to have a person homeless," says James Toomey from Mission Australia.

"It doesn't make sense for the state to ignore homeless people, as that's more expensive to taxpayers."

Mission Australia accepts that the Michael Project was relatively small in size and that more than half of those who entered the scheme dropped out.

But it says that's only to be expected with people who are, by definition, rootless and unsettled.

But Mission Australia still believes the programme could be scaled up nationally and serve as a template for similar operations in other countries.

"Every where has homeless people", says Toomey. "But we've shown that you can do something about it and save money.

"These are forgotten people at the margins of society and it's not right they are ignored, when our project is proof that they can re-engage and become full citizens again, not just burdens."

Gordon no longer feels like a burden. Every Monday you can now catch him at his local theatre rehearsing a play.

"We do a new piece every six weeks," he says. "I really enjoy getting stuck into the text and love performing."

"Would you ever be homeless again?" I ask.

"No, I will never be homeless again. Never. I might even take up painting, once more. Another cowboy, perhaps?"