The Shard: What’s it like to live near a skyscraper?

- Published

London has a spiky new steel and glass steeple - the Shard. This elongated pyramid is currently the tallest building in the European Union at 310m, but how does it feel to live in the shadow of such a giant?

Skyscrapers have been the symbol of the modern city for over a century.

In the past 50 years, buildings have been rising ever higher, majestically reaching for the sky and making the most of land values in crowded city centres.

But while tall buildings can be adored or reviled from afar, it is in their own neighbourhoods and at their own feet that their effects are most acutely felt.

And their height can cause big problems, such as strong winds at their base, casting long shadows and, when grouped together, creating noisy canyons.

And then there's the matter of looks. Not the all-too-obvious matter of the skyline, but the subtler one of how the building touches the ground.

London's Centre Point creates a gusty micro-climate

Wind creates several kinds of problems for tall buildings, says building engineer Max Fordham. In general, the higher you go, the faster the wind speed. And as wind speed doubles, the pressure exerted on a building quadruples.

When fast winds hit a tall building, the building can vibrate and sway from side to side. Engineers have to design buildings to cope with this level of loading.

But there's something else that happens - strong winds that would normally stay well above street-level can be forced groundwards, travelling at 20m a second.

A good example of this is Centre Point in central London. It's set perpendicular to the prevailing westerly wind that blows along the length of Oxford Street until it bangs into the monolithic facade of the 1960s tower.

In Leeds, the effect has even been connected to the death of a man crushed by a lorry in strong winds. He died near the city's tallest building, Bridgewater Place, and coroner Melanie Williamson <link> <caption>heard complaints about a "wind tunnel" effect since its completion</caption> <altText>BBC News</altText> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-leeds-16986600" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

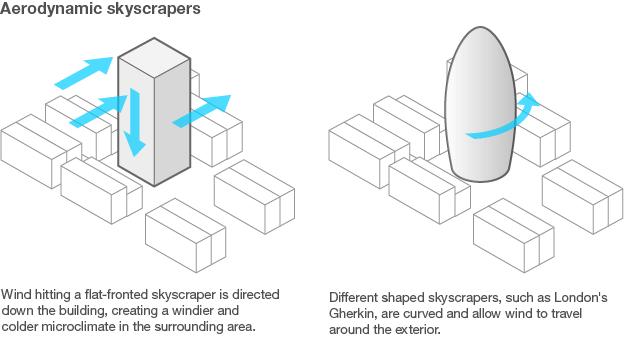

The wind flows down the front of tall building, causing gusty conditions at its base. "I should know," says Adrian Campbell, one of the structural engineers who designed 30 St Mary Axe (aka the Gherkin). "It's always windy when I am cycling past the building."

The Gherkin

It's colder too. The high winds at the foot of many tall buildings produce micro-climates that feel considerably cooler than surrounding areas.

There are, however, ways to cope with the wind. Campbell says that the curved surfaces of the Gherkin help wind to flow around the building without being forced downwards. Although not curved, the Shard's faceted, tapering silhouette aims for a similar effect.

Buildings can also be designed with canopies near the ground to protect pedestrians from wind gusts.

Buildings cast welcome shade in Sanaa

Tall buildings also cast substantial shadows. In hot climates, people exploit this, as in the old city of Sanaa in Yemen - a Unesco World Heritage Site of 10m-high clay walled buildings.

But in the UK, we welcome the sun. To sit outside on a rare sunny day and find you are shaded by a tower block some distance away can be annoying.

The Shard, however, is sited on the south bank of the Thames and so throws its shadow mostly across open water. "It is a very cleverly sited building," says architect <link> <caption>Steve Johnson</caption> <url href="http://www.thearchitectureensemble.com" platform="highweb"/> </link> , who has designed skyscrapers in the US Midwest. "The people most affected by the shadow will be in offices in the City."

According to Fordham, it is when tall buildings are grouped together to form canyons - as happens on Manhattan's Wall Street or 5th Avenue in Midtown - that the problems of shadow and noise become acute. The more gaps there are in the canyon-wall, the easier it is for sound waves to escape and for the street to seem quieter.

Skyscrapers are often thought of in their relation to the sky - the Shard's architect Renzo Piano talks of how his building is "a mirror tilted at the sky" and "flirts continuously with the weather, with the clouds". Yet the point at which a building joins the earth is just as important.

Gillian Horn, a partner of the award-winning architectural practice <link> <caption>Penoyre and Prasad</caption> <url href="http://www.penoyreprasad.com" platform="highweb"/> </link> , stresses the need "to build humanity into a tower". This is especially so at ground level, where passers-by are in a position to judge the material with which a building is draped (glass or stone or brick or concrete) and how that is treated.

"What does the tower give to the city? What is it like to approach it at street level? Those are the interesting challenges," says Horn.

Pedestrians deserve more than a blank facade, or a cluster of air vents and driveways for vehicle access. Careless designers of tall buildings can end up being dismissive of what Horn calls "the human level".

In order to encourage walking and street life, buildings need to interact with what is at ground level. Car parks, for instance, can sever a building's connection to its city. Campbell notes that the Gherkin only has about 20 parking spaces in the basement.

The final appearance of the Shard's ground levels isn't entirely clear yet, as work continues on the perimeter of the building.

But for such a tall building, it seems to come to earth surprisingly lightly. It is approached through small streets, and the white metal pillars of its support structure penetrate London Bridge Station, making the crystalline tower almost hover above the station below.

Piano and the building's developer Irvine Sellar both stress that this will be an accessible monument, with the public able to ascend to viewing platforms from which to gaze all the way across London.

"I will never be an advocate for tall buildings, in the sense that I don't believe that tall buildings are necessarily the only interesting thing, that's for sure," says Piano. "But if the tower gives back to the city more than what it gets from the city, then why not?"

Piano says that we should be building cities this way, not "creating a planet of suburbia". But perhaps the future lies between these extremes, for as Fordham points out, both bungalow and mega-structure ignore the real and pressing demands of the environment.

<italic>Renzo Piano was speaking to the BBC World Service and took part in the first of the </italic> <link> <caption>BBC World Service's Dream Builders series</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00tjz3x" platform="highweb"/> </link> <italic> which was recorded at the Riba.</italic>

<italic>All images in slideshow subject to copyright - click bottom right for details. Some images courtesy Getty Images, PA, Sellar Group and Renzo Piano Building Workshop.</italic>

<italic>Audio from BBC World Service. Music by Carly Rae Jepsen, Nell Bryden and KPM Music.</italic> <italic>Slideshow production by Paul Kerley. Publication date 15 June 2012.</italic>