A Point of View: Why are the Beatles so popular 50 years on?

- Published

The Beatles' first studio recording in 1962, soon after Ringo Starr joined the band

The Fab Four's music endures because it mirrors an era we still long for, says Adam Gopnik.

Over there this summer you are celebrating, as all of us over here know, a decades-old anniversary of uncanny auspiciousness: the Jubilee of an institution that has lasted far longer than many thought possible, transcending its native place in Britain to become a source of constant, almost unbroken reassurance to the entire world.

I'm referring of course to the truth that in a very few weeks we will celebrate the 50th anniversary of the first concert, and first photograph, of the four Beatles.

I'm looking at the picture now. It shows the Beatles, as they would remain, together, John, Paul, George and now at last Ringo in place at the drums, taken in that afternoon before one of their first public appearances on 22 August 1962.

And now I am looking at another photograph that shows the four in the very last photograph that would ever be taken of them - from 22 August 1969, exactly seven years later, to the day and, from the looks of the light, perhaps the hour.

There is something eerie, fated, cosmic about the Beatles - those seven quick years of fame and then decades of after-shock.

They appear in public as a unit on 22 August and disappear as a unit, Mary Poppins like, exactly seven years later. Or take their beautiful song "Eleanor Rigby". Though Paul McCartney can recall in minute detail how he made the name up in 1965, it turns out that in St Peter's Woolton Parish Church cemetery, just a few yards from where Paul first met John on 6 July 1957, there is a gravestone, humble but clearly marked, for one Eleanor Rigby.

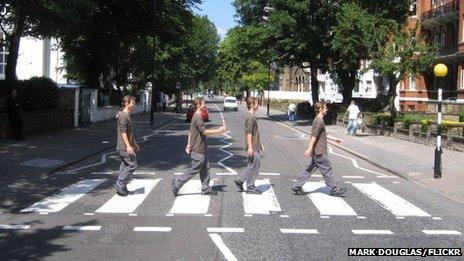

Paul must have made an unconscious mental photograph on that fateful day and kept it with him through the decade. Even things that they did in a pettish rush become emblematic: they took a surly walk across Abbey Road because they were too exhausted to go where they had meant to go for the album cover, and now every American tourist in London walks the same crossing, and invests their bad-tempered stride with charm and purposefulness and point.

Flickr user Mark Douglas gave his own rendition of the Abbey Road cover using a camera-timer and merging images of himself

The Beatles remain. It is no accident that the Queen's Jubilee, that other one, ended with Macca singing four Beatles songs. It wasn't just nice; it was only fitting. (Though it's a shame Ringo wasn't there to do the drumming.)

There's a popular video my kids like called "stuff people never say". Well, they don't say "stuff", and one of the things the video insists that people never say now is "I don't like the Beatles."

Everyone liked them then, and everyone likes them now. My own children fight with me about the Rolling Stones and are baffled by the Spinal Tappishness of Led Zeppelin (why do they scream in American voices?)

But the Beatles are for them as uncontroversial as the moon. Just there, shining on.

This is strange. Had the same thing been true for our generation - that the pop music that superintended our lives dated from before World War I - it would have been more than strange, bizarre. Why have they lasted?

The reason we usually give is that they reflected their time, were a mirror of a decade, the 60s, that we still long for.

But the longer that I have listened to them and the more that their time recedes into history, the more vital they sound.

I wonder, even, if truly historic pop figures don't always have a backwards relation to their time. Charlie Chaplin, one of the few artists to have a comparable allure, was at work after World War I, the era of the automobile and the machine gun, one of the most disruptive moments in human history.

But Chaplin's work, rooted in Victorian theatre and the Dickensian novel, evokes the values of the time before.

The city in City Lights and The Kid is the London of 1890, not the New York of 1920. His art, energetic on the surface, was elegiac beneath.

Charlie Chaplin's films evoked the values of a previous era

I think this is true of the Beatles, too. The Beatles were not provocateurs, though often mystics, and their great subject was childhood gone by, and what to make of the austere, rationed, but in many ways ordered and secure English world that they had grown up in, and that was now passing before their eyes, in part because of the doors they had opened.

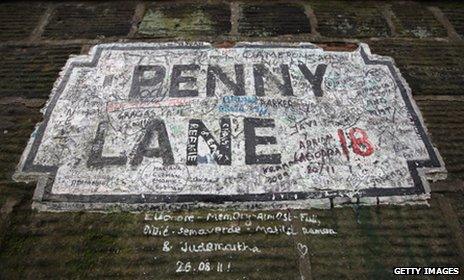

Their most enduring work, the singles Strawberry Fields and Penny Lane, tell on one side of the dream memory of a Liverpool garden where a lonely alienated boy could find solace, and on the other of a Liverpool street where a bright, sociable boy could see the world.

Remembered sounds - of brass bands and 20s rick-a-tick ornament their music and children's books. The Alice books particularly, fill their lyrics.

Sexual intercourse may have begun, as Philip Larkin says, with their first LP, but their subsequent ones rarely had too much intercourse with sex.

Their greatest hit singles, She Loves You, and Hey, Jude are songs of avuncular counsel, wise advice given by one friend to another who has got in over his head in a love affair. Peter Sellers did a hilarious piece as a middle-aged Irishman in a pub, using the words of "She Loves You" as natural dialogue passed over the pub table. "You know it's up to you. Apologise to her." It worked not because it was so incongruous but because it sounded so congruous, so sensible.

Landmarks such as this one found their way into Beatles' songs

The Beatles' music endures above all because we sense in it the power of the collaboration of opposites. John had reach. He instinctively understood that what separates an artist from an entertainer is that an artist seeks to astonish, even shock, his audience. Paul had grasp, above all of the materials of music, and knew intuitively that astonishing art that fails to entertain is mere avant-gardism.

We see the difference when they were wrenched apart: Paul still had a hundred wonderful melodies and only sporadic artistic ambition, while John still had lots of artistic ambition but only a sporadic handful of melodies. But in those seven years when John's reach met Paul's grasp, we all climbed Everest. (Not an arbitrary choice by the way: Everest was to be the title of their last album, and the place they had meant to go before they ended up going outside to Abbey Road instead.)

The fatefulness of their climb haunts many million others. I had moved with the girl who was to become my wife to New York city in the late fall of 1980, and it was with joy that we saw a birthday greeting from Yoko to John and Sean fill the sky just after we got there. That John was back at work in the studio, after five years away, as we soon learned he was, seemed a good omen for us. We were together in our tiny new home late at night when he was killed, just across the park. We might have heard the shots.

I don't think I've ever quite recovered from that night. My essential faith in the benevolence of the universe was shattered. Some compact that, at 20, I thought the world had made with me - that things turned out well, that you ended up in New York with a girl you were in love with and the Beatles across the park - seemed betrayed.

Or rather, I learned in a rush that night the adult truth, which is that the world makes no compacts with you at all, and that the most you can hope is to negotiate a short-term treaty with it - an armistice, which the world, like a half-mad monarch, will then break, just as it likes.

The Beatles were masters at harmonising

The Beatles' gift was for harmony, and their vision was above all of harmony. And harmony, voices blending together in song, is still our strongest symbol of a good place yet to come.

In the world of symbol and myth that music can't help but create, melody lies behind us, and calls us, as John's beautiful song "Julia" does, to our memory of a better past, or what we want to think was one.

Harmony as symbolic form always lies ahead, as the realised-here herald of a better world where all opposites will sing together as one. That's why even Bach and Handel ended their greatest works with a chorale - to cheer us on to a world we might get to by hearing a chorus that sounds like it's already got there.

Art makes us alive and aware and sometimes afraid but it rarely makes us glad. Fifty years on, the Beatles live because they still give us that most amazing of feelings: the apprehension of a happiness that we can hold, like a hand.