Women of Watergate

- Published

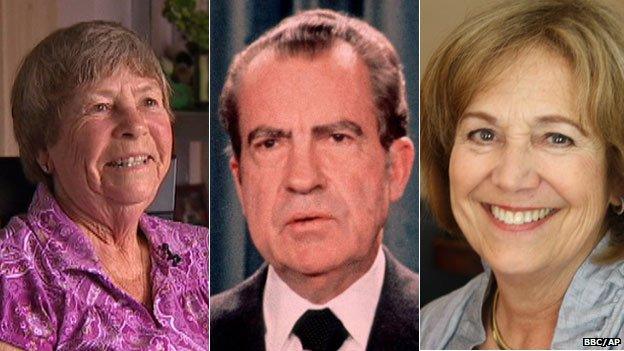

Some of the president's women: Judy Hoback Miller and Debbie Sloan were thorns in the side of Richard Nixon

The year 1972 was a defining year in American history but also a pivotal one for American women - with changes in the nation as a whole reflected in the stories of the female players in All the President's Men.

The essential book about Watergate is called All the President's Men for a reason. It recounts the in-depth investigation into the powerful men working for the White House and the many ways they abused their power, and the men who took them down - most famously, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, who painstakingly put the pieces together as reporters at the Washington Post.

The front pages of the book list a cast of characters crucial to the story, broken into descriptive categories: the president's men, the burglars, the judge, the senator, the prosecution and the Washington Post. Fifty-one of the 52 names listed are men.

The lone exception is the powerhouse publisher of the Washington Post, Katherine Graham. But she is far from the only woman in the Watergate story. Female characters play pivotal roles in the book, but their stories have mostly faded from memory.

'Minor people'

Take "the bookkeeper". While Deep Throat became the most famous anonymous source in journalism, the bookkeeper may have been more vital to exposing corruption inside the White House.

Last week, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein said: "The real turning point in the coverage of Watergate was when Carl found the bookkeeper. The bookkeeper had the details of the money and who controlled it and who got the money. You look at All the President's Men, I really think the bookkeeper is the key source."

The bookkeeper was Judy Hoback (now Judy Miller), at the time a young widow with a two-year-old daughter. She worked for the Committee to Re-elect the President (CRP), a Nixon fundraising group.

She was one of the few committee employees willing to talk to reporters. Her job tracking political payments gave her access to a lot of information, but it was her relative obscurity that gave her the ultimate power to help take down the president.

"So called 'minor people' were very important in unravelling this story," says Stanley Kutler, professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin and author of The Wars of Watergate.

"You start with people like that and you build your case. When you did get to the big boys, they were already well-trapped by the role of minor people. And many of those were women."

Raising consciousness

Both Watergate and the feminist movement had their roots in the 1960s, says Mary Thom, an early editor of the feminist magazine Ms, which was first published only a few weeks after the Watergate break-in.

"The feminist movement came a good deal out of the protest movement, and Watergate was Nixon's crazed reaction to how he felt about the interior threat of protest movements," she says.

But the women who played crucial roles in the story didn't see themselves as feminist crusaders.

"I never thought of myself as a 'woman journalist,' " says Marilyn Berger, who worked at the Washington Post with Bernstein and Woodward. "I was a woman at home, and at work I was a journalist."

Despite her success as a diplomatic reporter, she entered into the Watergate story when a White House staffer tried to woo her with tales of his misdeeds - only to be shocked and angry when she reported those tales in the paper.

"There was a pervasive assumption that to be female was to not be professionally serious or qualified," says Nancy MacLean, professor of history at the University of North Carolina.

Women in 1972 were living through a period of transition. An equal rights amendment to the US Constitution passed Congress but would be rejected by the states. Equal access to education would help the generation that came of age in the 1980s more than those living through the 1970s.

Adult women often straddled convention and progress, caught between the past and the future.

"Just because the law changed didn't mean the world changed, too," says MacLean.

Nixon the chauvinist

The cultural and political tension of 1972 is also apparent in the tales of two Washington marriages.

Debbie Sloan, wife of Committee to Re-elect the President (CRP) treasurer Hugh Sloan, worked at the White House as an assistant to the social secretary.

She met her husband there, who was then performing a similar role for the president. "We were the first White House marriage," she says.

After all, she adds, up to that point there hadn't been many young, single women working in the White House in a professional capacity.

Martha Mitchell was the wife of John Mitchell, the US Attorney General and the president's campaign manager. She also worked for the president, and was an early member of CRP.

When it became clear that CRP was embroiled in illegal and unethical activities, the Sloans worked together to figure out Hugh's next move. Martha Mitchell, however, was left in the dark.

She claimed she was plied with alcohol in an attempt to keep her quiet, and written off as "hysterical" when she demanded answers.

Bob Woodward called her "the Greek chorus of the Watergate story". Richard Nixon put the blame of the scandal at her feet.

"I'm convinced there would be no Watergate without Martha Mitchell, because John wasn't mindin' the store," he told David Frost in 1977. "He was practically out of his mind over Martha in the spring of 1972."

And that, says historian Kutler, is about as much credit Nixon would give to a woman.

"You had a president who had contempt for women being involved," he says.

On tape, Nixon confessed to nominating a weak female candidate to the Supreme Court so that she'd be rejected early in the vetting process.

It was a way to pacify his wife, who suggested a female nominee, without believing such a thing was possible.

"He was laughing behind her back," says Kutler.

But thanks to those who helped expose his involvement in Watergate, he wasn't laughing for long.

- Published17 June 2012