The cult of TED

- Published

- comments

Once a select forum of the great and good, the Technology Entertainment and Design (TED) conference now has millions of avid online fans. How did an elite ideas-sharing gathering go mainstream?

Falling animals, misbehaving toddlers and footage of Justin Bieber may populate the bulk of any YouTube most-viewed list.

But amid the viral clips and pop music promos is a series of videos that seems to go against all received wisdom about what online audiences like to consume.

Their tone is sunnily optimistic, go-getting, Californian, with titles like Information Is Food, Crowdsource Your Health and Inventing Is the Easy Part.

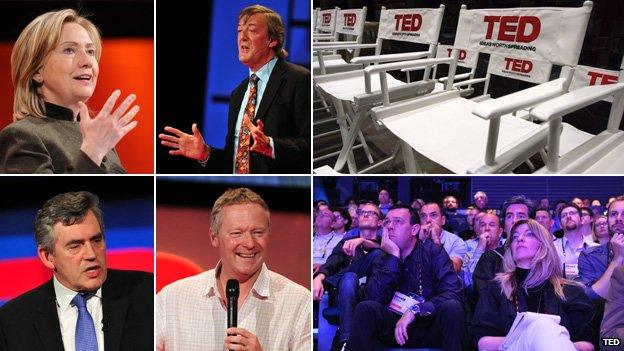

They feature luminaries such as Stephen Hawking, JK Rowling and Bono delivering 18-minute lectures about big ideas - technology, culture, the environment, science, social trends.

Yet although there is nary a Lolcat in sight, the YouTube channel of the Technology Entertainment and Design (TED) conference has attracted nearly 112 million views.

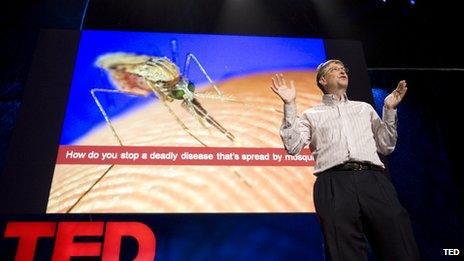

Bill Gates unleashed mosquitoes on a TED audience in 2009

The talks have a habit of catching on. TED attendees were given a preview of Al Gore's <link> <caption>lecture on climate change lecture, later popularised in An Inconvenient Truth</caption> <url href="Http://www.ted.com/talks/al_gore_on_averting_climate_crisis.html" platform="highweb"/> </link> . Biologist Richard Dawkins' 2002 lecture on "militant atheism" laid the groundwork for the arguments set out in his <link> <caption>hugely controversial book The God Delusion</caption> <url href="http://www.ted.com/talks/richard_dawkins_on_militant_atheism.html" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

Others have entered the realms of the downright strange, such as when <link> <caption>Microsoft founder Bill Gates unleashed live mosquitoes</caption> <url href="Http://www.ted.com/talks/bill_gates_unplugged.html" platform="highweb"/> </link> into the auditorium during a talk on malaria because "there's no reason why only poor people should have the experience" (the insects were not infected).

It's an impressive level of public interest in an event sneered at by detractors as an expensive talking-shop-cum-networking-event for latte-wielding, iPad clutching, West Coast blue-sky thinkers.

Indeed, the gathering at which the talks are filmed would appear to run counter to every principle on which the online era of interactivity is supposed to be based.

To attend the next TEDGlobal conference in Edinburgh from 25-29 June, potential attendees must apply for $6,000 (£3,700) annual membership.

Lectures are entirely one-way - delivered by the speaker to the audience with no question-and-answer sessions. But to be accepted, applicants must be judged likely "to be a strong contributor to the TED community, the ideas discussed at TED, and the projects that come out of the conference".

However, internet users accustomed to open-access information seem scarcely put off by these barriers. TED has two million "likes" on Facebook and its own online social network, TED Community, with 120,000 members.

The answer lies in the decision by TED curator Chris Anderson in 2006 to upload videos of the event on its TEDTalks site as well as on YouTube and iTunes - opening up this unashamedly exclusive event to public consumption.

For many, indeed, TED has become more than just an online educational resource - it is a hobby, an identity, a key part of one's social networking profile.

Ray Willmouth, 33, a footwear buyer from Muswell Hill, north London, is typical of the conference's many Facebook fans.

A regular online viewer of the talks for four years, he cannot ever imagine spending thousands to attend an event in person - but he does enjoy being part of a community forged around ideas.

"People like to feel like they're part of a tribe," he says. "It's about how you identify as a person. I don't think that's a bad thing.

"I've heard people say it's a bit like a cult. But the difference between TED and being in church is that all the talks are verifiable by science - it's done within the spirit of critical thinking."

The first TED event took place in 1984. Since then, the non-profit organisation has branched out beyond its annual conferences (admission: $7,500, or £4,700) in Long Beach and Palm Springs, California.

As well as the yearly TEDGlobal fairs in Edinburgh, there are TEDIndia and TEDWomen events as well as a yearly $100,000 (£62,800) TED Prize. Fans are permitted to stage their own events under the TEDx banner.

The admission fee doesn't buy the chance to ask questions

"The paradox of TED is that it's the most elitist organisation for ideas and at the same time one of the most open," says blogger, academic and media consultant Jeff Jarvis.

This apparent paradox has been the focus of many critics. Despite this, TED's European director Bruno Giussani, who curates TEDGlobal, insists there is no contradiction between the ideals of openness and the price tag.

"The conferences are exclusive and expensive," he acknowledges. "But the revenue they generate pays for everything else.

"The web has expanded the amount of silliness out there but also the amount of seriousness. What TED reveals is that there's clearly a big thirst out there for different ways of sharing knowledge. This was under served and we tapped into it."

Not everyone, however, buys into the overarching philosophy of TED. A more cynical view is expressed in the Twitter feed @RandomTEDTalks, which offers "randomly generated" spoof titles (a sample: "Wearable Tech For Sexy Penguins", "My Dataset Channels The Power Of Awesome", "Let's Hide A Happy Secret In Orbit Around Saturn").

Others take issue with the very concept of a VIP event that less well-funded web browsers are invited to gaze into from the outside.

For social media theorist Nathan Jurgenson, the exclusivity undermines any lofty ambitions of idea-sharing.

"The basic idea of smart ideas being presented in a way that's accessible is a great one, but all you get from TED are the ideas of Silicon Valley," he says.

"It has a cultish feel to it. The speakers use a lot of terms like 'magical' and 'inspirational'. It's almost the religion of the knowledge class."

Certainly, there are overtones of the after-dinner motivational speech in many of TED's most popular talks.

But for its enthusiasts, the very fact it has induced such a wide audience to engage with often complicated ideas makes it a force for good.

"It is elitist, but thank goodness the best bits are there online for everyone to see," says philosopher Alain De Botton, who has delivered talks at two TED events.

Alain de Botton has addressed the conference twice

"Unless you are a keen networker from Silicon Valley, the punters at home are getting the best bits."

And indeed, it's not difficult to conclude that the sense of belonging to a privileged elite is, consciously or otherwise, a significant part of the appeal for many ordinary TED fans with little prospect of ever actually attending a conference.

"They fancy themselves as smarter because they know TED," says Jarvis. "It's a status marker.

"You have the people who are inside TED, the people who are around TED - the fans watching at home - and people who are outside TED and mock it.

"Hasn't it always been thus? We always want to look through the keyhole and Chris Anderson knows that. It has increased the value of the brand."

If he is correct, then even TED's fiercest critics are a crucial component of the TED experience. The big idea juggernaut rolls on.