Minitel: The rise and fall of the France-wide web

- Published

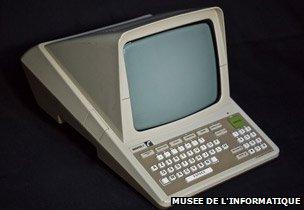

France is switching off its groundbreaking Minitel service which brought online banking, travel reservations, and porn to millions of users in the 1980s. But then came the worldwide web. Minitel has been slowly dying and the plug will be pulled on Saturday.

Many years ago, long before the birth of the web, there was a time when France was the happening-est place in the digital universe.

What the TGV was to train travel, the Pompidou Centre to art, and the Ariane project to rocketry, in the early 1980s the Minitel was to the world of telecommunications.

Thanks to this wondrous beige monitor attached to the telephone, while the rest of us were being put on hold by the bank manager or queueing for tickets at the station, the French were already shopping and travelling "online".

Other countries looked on in awe and admiration, and the French were proud.

As President Jacques Chirac boasted: "Today a baker in Aubervilliers knows perfectly how to check his bank account on the Minitel. Can the same be said of the baker in New York?"

Chirac was speaking in 1997, exactly half way through the life-cycle of France's greatest telecoms innovation.

At the time, he could be forgiven for thinking it would last forever. This was the high point, with nine million Minitel sets installed in households around the country, an estimated 25 million users, and 26,000 services on offer.

But of course, the story was already written. The internet was moving in.

Today bakers from Timbuktu to Tallahassee are not just consulting their bank statements online, but doing just about everything else as well.

And so on Saturday, exactly 30 years after it was launched, the Minitel is bowing out. After that, the little beige box will answer no more.

It was born in the white heat of President Valery Giscard d'Estaing's technological great leap forward of the late 1970s.

An expert report then concluded that with proper investment the nation's telephone network could be complemented by a visual information system, accessed through screen-keyboard terminals.

"As well as being a technological project, it was political," says Karin Lefevre of France Telecom. "The aim was to computerise French society and ensure France's technological independence."

About 600,000 are estimated to remain in use

Rolled out experimentally in Brittany, Minitel went national in 1982, offering the telephone directory and not much else.

Gradually the offer increased to a vast array of services - banking, stock prices, weather reports, travel reservations, exam results, university applications, as well as access points to various bits of the state administration.

All users had to do was dial up a number on the keyboard, then follow instructions that juddered out in black and white across the screen.

It may have been the ultimate in computer clunk, but it worked.

"Of course it looks terribly old-fashioned by today's standards," says Lefevre. "But it was simple to use. You pressed a button and it did something. Just like on a tablet today."

Apart from ease of use, two other factors ensured Minitel's success. First was that it was distributed free of charge by the then state-owned France Telecom (or its predecessor the PTT).

This meant that even the poorest of households contained a set, subsidised by the taxpayer.

The other reason was the variety of content, facilitated by a business model that was not exactly free-market but for a while proved highly effective.

From the start, there were commercial interests that were highly suspicious of Minitel - the newspaper industry, which feared the new creation would drain vital small ads revenue.

So France being France, the government intervened to save the press. It made a rule which said that the only institutions entitled to provide services on Minitel were registered newspapers.

Soon these were creating all kinds of new ideas, leaving to France Telecom the hassle of collecting and then passing on their monthly fees.

The most lucrative service turned out to be something no-one had envisaged - the so-called Minitel Rose.

With names like 3615-Cum (actually it's from the Latin for "with"), these were sexy chat-lines in which men paid to type out their fantasies to anonymous "dates", most of them sitting in the 1980s equivalent of call-centres.

Until very recently, billboards featuring lip-pouting lovelies advertising the delights of 3615-something were ubiquitous across the country.

Some people are said to have spent thousands of francs every month on the Minitel Rose, and a number of entrepreneurs certainly got rich.

It turned out to be quite easy to set up a newspaper. Once you were registered, you quietly let it die and got on with making money from Minitel.

Today, as switch-off approaches, debate rages in France about Minitel's legacy, and whether in retrospect it has proved more of an embarrassment than a mark of pride.

What once was shiny and new now looks like a shoddy bad investment - of interest to the retro market, but not to anyone else.

One thing that is very telling is that Minitel was a uniquely French institution. It never made it abroad (apart from Belgium).

Briefly in the early 1990s, France Telecom did set up a pilot project in Ireland. The idea was to test Minitel in a small Anglophone environment, with an eye on a bigger launch in the UK or the United States.

A few thousand terminals were sold, but it never took off.

"I remember when I joined in 1990, it all felt extremely funky. My friends were all very impressed that I was bringing in this new sexy piece of French kit," says Gary Jermyn, who was the joint operation's finance director.

"But there were so many problems. First of all, unlike in France, we were selling the terminals, not giving them away. That was a huge handicap. And then the internet was arriving, and that was the death knell.

"Minitel wasn't an open platform. It only provided Minitel services, which was quickly going out-of-date as a model. Also by the early 1990s the terminal itself was the clunkiest piece of desk manure you could imagine. It was embarrassing."

A decade later, Jermyn says all that remained in Ireland were a few disused Minitel sets gathering dust in a handful of remote B&Bs (a tourist booking service had been one of the key ideas).

For Benjamin Thierry, a Sorbonne university lecturer and co-author of the recent book on Minitel, France's Digital Childhood, Minitel's failure to penetrate foreign markets is a classic French experience.

Minitel brought online banking to millions of users in the 1980s.

"When the French try to sell overseas, they insist on selling a whole system lock, stock and barrel. They don't know how to adapt, to break it up into parts. That just puts people off," he says.

Indeed the whole Minitel adventure can be seen as a typical French experience.

Only in France could the public resources have been mobilised to give the project its initial boost. So for a few years, the country was the envy of the world.

But then, immobility and inertia - as the market simply passed by.

"The failure of Minitel was not one of technology," says Benjamin Bayart, head of France's oldest internet provider, French Data Network.

The design of the Minitel changed over time

"It was the whole model that was doomed. Basically to set up a service on Minitel, you had to ask permission from France Telecom. You had to go to the old guys who ran the system, and who knew absolutely nothing about innovation.

"It meant that nothing new could ever happen. Basically, Minitel innovated from 1978 to 1982, and then it stopped," he says.

But others are less critical.

Valerie Schafer, Thierry's co-author, says "the way Minitel is now fobbed off as risible and old-fashioned" is unfair.

"People forget that many of the ideas that helped form the internet were first of all tried out on Minitel. Think of the payment system, not so different from the Apple app-store.

"Think of the forums, the user-generated content. Many of today's web entrepreneurs and thinkers cut their teeth on Minitel," she says.

"The world did not begin with the internet."