Kenyans and lions vie for territory

- Published

As Kenya's population has grown over the years, urban areas have been consuming more and more countryside, with humans and wildlife increasingly vying for the same territory.

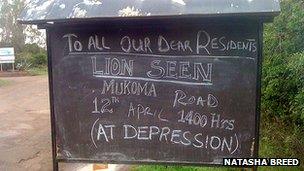

The sign at the entrance to my neighbourhood read: "To all our dear residents - Lion seen Mukoma Road".

The area borders the Nairobi National Park and we are used to hearing lions calling at night (sometimes leopard and hyena too) but the idea that one might encounter a lion while opening the gate was rather thrilling.

It felt a bit like 40 years ago, when a cricket match at the local primary school had to be abandoned while the delighted children - my brother among them - watched from the safety of the classrooms as lions strolled across the pitch.

However I was not destined to have to complete the 100-yards dash to outrun a lion to get to my front door because I had to go away. But when I returned six weeks later, there was a new sign, "Be aware - Lioness along Mukoma Road", along with an emergency number to call.

Evidently somebody called the number, as action was taken. One lioness was shot and another - together with four cubs - was taken to the Nairobi Animal Orphanage until a decision could be reached about their future.

And then, last Thursday's newspaper headlines screamed in unison:

"DEATH OF LIONS A BIG LOSS"

"KING OF JUNGLE DOWN AND OUT"

"FURIOUS VILLAGERS SLAY SIX LIONS"

"HASIRA HASARA'' in one of the Kiswahili papers, meaning The Damage of Wrath.

While each editorial differed slightly, the photographs all told the same story. Grisly images of the limp bodies of lionesses being hefted into a Park vehicle by uniformed rangers while a spear-wielding crowd looked on.

And there were lurid pictures of punctured, blood-stained animals being exhibited, heads lifted by the ears, eyes staring unseeingly, tongues lolling from gaping mouths. Two of the lions were cubs.

In the early hours of the morning - following an attack on a flock of sheep and goats - furious villagers, armed with traditional weapons and using vehicles to herd the marauding lions together, made a distress call to Kenya Wildlife Service and held the lions at bay until rangers arrived.

The rangers tried to placate the angry men, who demanded a veterinary officer be brought to sedate the animals and take them away.

After an hour though, the villagers' patience finally ran out and six lions were attacked and killed - all in the space of 10 minutes, according to the press. Two others escaped.

Historically, after rains, lions leave the park, following herbivores which disperse into outlying areas. Not so many years ago, the migration of zebra and wildebeest between Nairobi and Amboseli national parks was second only to the great Mara-Serengeti migration.

But whereas there used to be a "wildlife corridor" of land where both prey and predators could spread out, now human habitation blocks the animals' way.

Inevitably predators encounter livestock and there are heavy losses on pastoralists and farmers alike.

There is no denying that, to a stockman, the loss of any livestock is drastic and the danger of coming into contact with a predator while trying to protect one's herds, considerable.

Paula Kahumbu, chairperson of the Friends of Nairobi National Park, makes regular visits to the adjoining community.

She tells me the pastoralists have reported frequent attacks on their livestock in the past six months and have demanded compensation for loss of their animals. While there is a government policy in place to pay compensation for loss of life or injury to humans caused by wildlife, none exists to replace lost livestock.

This incident serves to highlight the challenges faced by lions and other wildlife in Africa today. Combined with the burgeoning human population, land-use policies are changing. Space is precious.

There are now thought to be only 20,000 lions in Africa.

Like many wild animals, lions survive by moving. As zebras, wildebeests and antelopes follow the rain for fresh pasture, predators follow the herbivores. But in Kenya, with human habitation spreading out across the country, the animals' habitats are becoming no more than islands in a sea of humanity.

Is there really room for lions in developing Africa?

Naturally the welfare of humans takes precedence over that of wild animals. Yet in Kenya, tourism is one of the main sources of revenue, contributing significantly to the economy, and there is surely no beast more evocative of Africa than the majestic lion.

According to Maasai legend, when a lion roars in the darkness across the savannah, he is saying, "Whose land is this? Mine, mine, mine…"

But it isn't - not any more.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent:

BBC Radio 4: A 30-minute programme on Saturdays, 11:30 BST.

Second 30-minute programme on Thursdays, 11:00 BST (some weeks only).

Listen online or download the podcast

BBC World Service:

Hear daily 10-minute editions Monday to Friday, repeated through the day, also available to listen online.

Read more or explore the archive, external at the programme website, external.

- Published9 April 2019