The eurozone's religious faultline

- Published

Discussion among eurozone leaders about the future of their single currency has become an increasingly divisive affair. On the surface, religion has nothing to do with it - but could Protestant and Catholic leaders have deep-seated instincts that lead them to pull the eurozone in different directions, until it breaks?

Following the last European summit in Brussels there was much talk of defeat for Chancellor Merkel by what was described as a "new Latin Alliance" of Italy and Spain backed by France.

Many Germans protested that too much had been conceded by their government - and it might not be too far-fetched to see this as just the latest Protestant criticism of the Latin approach to matters monetary, which has deep roots in German culture, shaped by religious belief.

Churchgoing has been in decline in Germany as elsewhere as secularisation has spread, but religious ideas still shape the way Germans talk and think about money. The German word for debt - schuld - is the same as the word for "guilt" or "sin".

Talk of thrift and responsible budgeting comes instinctively to Angela Merkel, daughter of a Protestant pastor.

Merkel's frequent assertion that "there is no alternative" to austerity policies (while reminiscent to Britons of Margaret Thatcher) has been likened to the famous stubborn statement by German Reformation leader Martin Luther: "Here I stand. I can do no other".

The new German president, Joachim Gauck, who might play an important role in constitutional arguments about the single currency, is also from the Protestant fold - he is a former Lutheran pastor.

The country's population is fairly evenly divided between Protestants and Catholics - as well as those of other faiths, or none - and Merkel's and Gauck's ascent symbolises changes in Germany since reunification in 1990.

Former West German Chancellor - and Catholic - Konrad Adenauer signed the unifying Treaty of Rome in 1957

Both lived in East Germany, a historically Protestant territory, while West Germany had several influential Catholic political leaders, who, in earlier post-war decades, had joined in broad Catholic enthusiasm for European integration.

Former West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, a Rhineland Catholic highly distrustful of Protestant Prussian traditions to the German east, led West Germany into the signing of the Treaty of Rome in 1957.

This created the European Economic Community, forerunner of today's EU. And there was a clear geographical fit between the six countries which signed and the territory of Charlemagne's Holy Roman Empire.

Charlemagne, claimed by modern European unifiers as a kind of patron saint, had created a new currency for his territories - the livre carolienne.

Helmut Kohl, who took Germany into economic and monetary union in the 1990s, was another Catholic Rhinelander constantly visiting cathedrals and speaking of the ancient spiritual roots of a united Europe.

There was much talk of the Germans sacrificing their beloved Deutsche Mark currency "on the altar of European unity".

But German reunification at that time also meant the capital moving back to Berlin, away from closer Catholic connections felt in the west and south of the country.

And the eurozone crisis has intensified a deep-rooted debate about whether Germans, shaped by Protestantism, are fundamentally different from Catholic "Latin" countries and their allies.

German banking has, from medieval times, been more cautious than that in Italy and Spain. And sceptical Germans looking at the history of previous currency union troubles point to the 19th Century Latin Currency Union.

Germany, unifying under Prussian leadership through its own customs union, did not join. The Latin Union struggled to survive after a number of countries, notably the Papal States, minted and printed more money than they were meant to.

Politicians or states undermining money have diabolical overtones for angst-filled Germans.

An illustration from the 1800s shows Faust in his study with Mephistopheles

In Goethe's Faust, one of the most famous works in German culture, Mephistopheles persuades the Holy Roman Emperor to issue a new paper currency - despite one of his advisers warning that this is the counsel of Satan.

Order duly breaks down as the Emperors' subjects go on a binge bearing no relation to their real wealth.

Weimar Republic hyperinflation in the early 1920s - when "money went mad" and all moral as well as economic order was seen as collapsing - seemed a diabolical vision made real.

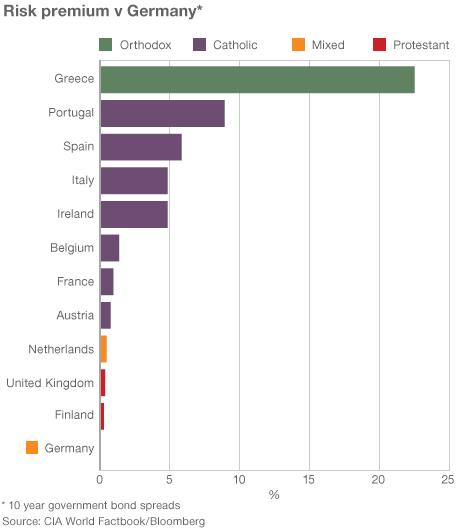

Some in Germany suggest today's eurozone would be better dividing, with some kind of Latin Union on one side, and on the other a German-led group of like-minded countries including perhaps the (Calvinist) Dutch and the (Lutheran) Finns.

The former head of the German industry association, Hans-Olaf Henkel, has said that "the euro is dividing Europe".

He wants the Germans, Dutch and Finns to "seize the initiative and leave the euro", creating a separate northern euro.

A new split along ancient lines? The government in Berlin has begun to plan for what it sees as a hugely significant anniversary in 2017 - 500 years since Luther began The Reformation.

He was protesting against indulgences, a controversial attempt by the Papacy to solve its fiscal problems by persuading Europeans to buy absolution from their sins.

One German commentator, Stephan Richter, has suggested mischievously that the eurozone's problems would have been prevented <link> <caption>if only Luther had been one of the negotiators of the Maastricht treaty</caption> <url href="http://www.theglobalist.com/storyid.aspx?storyid=9623" platform="highweb"/> </link> , deciding which countries could join the euro.

"'Read my lips: No unreformed Catholic countries,' he would have chanted. The euro, as a result, would have been far more cohesive," says Richter.

Richter is himself a Catholic, but an admirer of thrifty economics. "Too much Catholicism" he suggests, "is detrimental to a nation's fiscal health, even today in the 21st Century".

But he believes some historically Catholic countries, such as Austria and Poland, may have come under more Germanic influence due to their geographical proximity. They are "Catholics perhaps, but with a healthy dose of fiscal Protestantism," he reasons.

Commemorations in 2017 will doubtless try to stress that Reformation divisions between Protestants and other reformers and Catholicism were not too great.

But the usually thrifty government under Chancellor Merkel has already promised 35 million euros to mark this birth of Protestantism.

And where will the eurozone be in 2017?

Still intact? Or coming to terms with a new historic divide between the Latins and the preachers of Protestant thrift?