A Point of View: A time when violence is normal

- Published

Chaos and carnage hover over the novels of Cormac McCarthy and the writings of thinker Thomas Hobbes. It's not a love of domination that makes people violent, but the need for safety, says philosopher John Gray.

<bold>(Spoiler alert: Key plot details revealed below)</bold>

"War is god".

This is the sermon preached by "the judge", one of the central characters in Blood Meridian, a visionary novel by the American writer Cormac McCarthy.

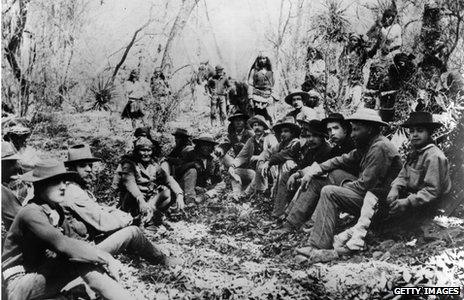

Set in the Texas-Mexico borderlands in the mid-19th Century, the book records the experience of a runaway, a teenage boy described throughout as "the kid", who falls in with a gang of bandits who make a predatory living by killing the region's Apache Indians in order to claim a bounty on the scalps.

Led by a former US army officer and mercenary, the band of scalp-hunters actually operated in the American Southwest at the time the novel is set, preying on Mexicans and Americans as well as the indigenous population until an Indian raid put an end to it, killing and scalping the gang's leader and most of its members.

The novel recounts the kid's life with the marauders, and ends with him - by then a man - apparently being killed by the judge in an outhouse of a Texas saloon.

An unremitting chronicle of gruesome savagery, Blood Meridian has been read as a subversive take-down of the traditional Western novel, an indictment of the idea of Manifest Destiny - the belief that the Anglo-Saxon race was destined to conquer the American continent - and a fictional meditation on the nature of evil.

It is all of these things, but more than anything else, it seems to me, the book recreates a time when violence was normal.

Here in Britain - and to a lesser extent in Europe and America - we tend to think of violence as an interruption of civilised existence.

It is hard to square this with the history of the 20th Century, when Europe was a site of mass killing on an unprecedented scale and vicious colonial wars were fought in Africa and South East Asia.

Today images of carnage most recently in Syria, and also in Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan and other places, are broadcast continuously in the 24-hour media.

The vast, industrial-style wars of the last century may have been left behind. But they have been followed by other forms of human conflict, in their way no less destructive. No longer simply a battle between states, war has become - as it was in the time of Blood Meridian - a deadly struggle among and within peoples.

Human beings use violence in many forms for a multitude of different reasons:

to defend themselves from attack

seize wealth and natural resources

impose their beliefs on others

protest intolerable injustice

and at times simply to find temporary relief from boredom.

Seeking peace in 19th Century America

Yet many people want to believe that human beings are essentially peaceable creatures, who turn on one another only when they have no other alternative. Violence, these people insist, is contrary to our strongest needs and impulses, which lead us to live and work together - in other words, humans are naturally predisposed to be civilised.

A canonical statement of this view was presented by a thinker commonly regarded as having a grimly realistic view of human beings, the 17th Century philosopher Thomas Hobbes.

When you hear the term Hobbesian, you think of people at each other's throats, struggling for power in a situation of chaos. This is what Hobbes called a "war of all against all".

"In the first place," the philosopher famously wrote, "I put for a general inclination of all mankind, a perpetual inclination of all mankind for power after power, that ceaseth only in death... Where there is no common power, there is no law, where no law, no injustice... No arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death: and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short."

These lines from Leviathan - Hobbes' best-known work and a masterpiece of English prose - have been read as meaning that humans are by nature violent animals.

Their true meaning is virtually the opposite. A bold thinker but a timid man: "I was born a twin to fear," he confessed. Hobbes believed that humans are driven to attack and prey on one another mainly by fear of uncertainty. It's not a love of domination that makes people violent, but an overpowering need for safety.

This isn't the only impulse that impels humans to be violent - Hobbes also mentions the desire for gain and the love of glory - but it is fundamental in his account of how they escape from violence.

Moved by a combination of reason and fear, Hobbes believed, human beings will contract with each other to create a sovereign - an absolute ruler who will prevent any slide into anarchy.

Under the shelter of strong government, humankind can enjoy "commodious living" - Hobbes' term for a civilised mode of life in which we can live and work together without fear.

Interpreted as a metaphor rather than a literal account of events, there is a good deal of truth in Hobbes' story. In historical crises, people have often looked to strong leaders to deliver society from anarchy.

Lenin's dictatorship was welcomed, at least to begin with, by Russians who opposed his programme because they hoped he would install some kind of order. In interwar Europe, dictatorship was popular in many countries because it seemed to offer a way out from economic and social chaos.

Many Russians thought Lenin's dictatorship would install order

Yet there have been many cases when human beings have adapted to violence for long periods. During China's era of warring states, and Europe after the fall of Rome, violence was at high levels for centuries.

A chronic state of lawlessness existed in large parts of North America throughout much of the 19th Century.

The same has been true in Lebanon, parts of Africa and some countries in Latin America. While humankind may fear violence, human beings have often learnt to live with it.

Blood Meridian has been interpreted as presenting a Hobbesian view of human nature, but what it shows is something that Hobbes did not envision - violence as a way of life.

As McCarthy presents them, violence does more for the gang than enable them to prey on others. It gave their lives - poor, nasty and short as they were - a kind of sense and significance.

For Hobbes, human beings are solitary creatures, who want nothing more than simply to go on living.

People often learn to live with violence

But we are not isolated individuals. We live in groups, and some of our best and worst qualities come from the need to form bonds with others. People will readily give up their lives to protect their children, while McCarthy's gang embodies a savage kind of solidarity in which its members fight, kill and die together.

Again, for Hobbes the only reason for killing is to pre-empt being killed yourself. But terrorists who go to certain death in order to wreak death on others do not do so for the sake of self-preservation.

What they are preserving is an image of themselves as part of a group or a cause, without which they feel aimless and empty.

In a passage in Leviathan that undermines much of the rest of the book, Hobbes writes of "the privilege of absurdity; to which no living creature is subject, but man only".

Here Hobbes was right. Humans alone among the animals are ready to kill and be killed in order to secure a meaning in their lives.

Where he went wrong was in thinking that violence can be tamed principally by the use of reason, an illusion of the European Enlightenment, of which Hobbes was one of the first great exponents.

We cannot escape the "war of all against all" by any kind of contract. Learnt slowly and painfully, the practices of civilised life are permanently fragile and precarious. Here the visionary novelist is more realistic than the rationalist philosopher.

Violence cannot be eradicated, because its ultimate source is in the warring impulses and fantasies of human beings.

This is the truth conveyed in McCarthy's great novel - civilisation is natural for human beings, but so is barbarism.