The white elephants that dragged Spain into the red

- Published

The terminal building of Ciudad Real International Airport stands dormant after closing in April 2012

Europe has already bailed out Spanish banks, now Spain's regions are clamouring for money from central government - and one of the reasons for this is their lavish spending on white elephant building projects, such as the airport at Ciudad Real, south of Madrid.

It has one of the longest runways in Europe but today there are no planes, only hawks and falcons gliding in the still heat over the arid yellow landscape of Don Quixote's Castilla La Mancha.

Rabbits pop up around the state-of-the-art terminal, built of steel, glass and gleaming white concrete.

The airport of Ciudad Real opened in 2008 but it closed in April 2012. The luggage trolleys are now trussed together in the car park gathering dust and cobwebs.

It is not the only white elephant to stomp across Spain's landscape. It is merely one of the herd, a monument to the country's burst construction bubble which brought down its banks.

When a local construction magnate came up with the idea of an airport in Ciudad Real, money was sloshing around Spain for public works.

It was the 1990s and every town in every region had a grand project to set itself apart and bring in the visitors. Bilbao was getting its own Guggenheim museum, so why shouldn't Ciudad Real have its own airport?

"We had an attack of wealth, we didn't know how but suddenly we were rich," says Miguel Angel Bastenier, senior columnist at the left-of-centre daily El Pais. "There was such a frenzy for investing money and people got inebriated."

The airport in Ciudad Real was to be a private project, for private profit, but the business people behind it had no problem getting political support.

Before their collapse, Spain's local savings banks (the cajas), were different from other banks in one crucial way - local politicians sat on the board. So companies needed political support for large projects to encourage the cajas to invest.

Both the main political parties were in favour says Santiago Moreno, a spokesman for the socialist PSOE party which controlled the regional government at the time.

"Expert studies commissioned by the airport investors said it would create 6,000 jobs and a boom for the economy. There would have been a before and after for Ciudad Real."

The walkway from the airport to the railway station remains incomplete

But the airport opened its runways to a world in the worst recession for nearly 100 years. Caja Castilla La Mancha became the first of Spain's local savings banks to go under in the crisis, with a rumoured 70% stake in direct and indirect investment in the airport.

Many more of Spain's cajas have since had to merge or be taken over, exposed to toxic debts. Should they have been speculating on Spain's construction boom? The Bank of Spain has fined two of the politicians who sat on the board of Caja Castilla La Mancha for what it calls "serious violations".

"You might think the airport failed because of the crisis, but I am convinced that the shareholders never thought it (the airport) would work. The only profit in this airport was the building of it," says local investigative journalist Carlos Otto.

The official bankruptcy report for the airport seems to back this up. It says:

"The loans taken out were enough to cover the construction phase but no thought was given to the investment needed to make the airport function as a business."

Banks approached by the shareholders for further loans said they didn't think the business model for the airport was viable, the report says.

It goes on: "The construction itself of the airport provided the first profit for the investors because they signed contracts with their own construction companies."

"It was never run as a proper business," said a former worker at the airport who wanted to remain anonymous. He hasn't found another job and worries he won't get one in Ciudad Real - where everyone knows everyone - if he speaks out about how the airport was run.

"We had races on anything that had wheels," he told us. "We even had races on the floor-polishing machines - we were all so bored. Some people used to go out to pick asparagus or catch rabbits…"

There was little to do. There were international flights from London Stansted, and within Spain from Barcelona and Palma de Mallorca. But in its last year not even one flight a day landed on the 4.2km runway, designed - ambitiously - to service the new Airbus 380, the world's largest passenger airliner.

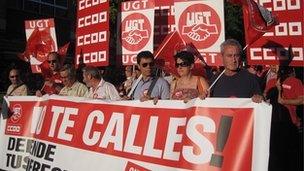

Residents of Ciudad Real demonstrate against the cuts

Carlos Otto believes the private investors who pushed the airport project assumed the regional government would ensure its profitability by subsidising airlines to fly there.

The regional government is now controlled by Spain's Popular Party which accuses its predecessor of wasting millions of euros. It is still not known how much the whole airport venture actually cost. Estimates run from 356 million euros to one billion euros.

This lack of transparency is one of the problems that led to Spain's economic crisis according to David Cabo, representative of Civio, a foundation that lobbies for freedom of information.

"Public servants are not used to being monitored, their accountability isn't common in Spain. It's terrible because you have many opaque layers of government and each of those control public money."

Juan Jose Toribio, an economist with Spain's IESE business school, says that to tackle Spain's problem of white elephant projects you first have to tackle the country's sacred cows - the semi-autonomous regions.

"Regional governments enjoy the possibility of spending and inaugurating public works but they don't run the political risk or cost of raising taxes. Someone should be held responsible for this and perhaps we should return to a much more centralised system."

But even with an absolute majority in parliament, the Popular Party may find centralisation harder to achieve than austerity.

At Cruz Prado school in Ciudad Real, daily drop-off resembles a picket line, with parents letting off fire-crackers and shouting through loud-hailers. They are demonstrating against the local government for failing to finish construction of a new canteen and playground. For the last two years the project has remained a wreck of rubble - stalled because the money has run out for the next generation.

One of the parents, Milagros Coronado, says she feels angry - and guilty.

"I shouldn't because it wasn't my decision to build the airport, but I feel guilty for having liked the idea so much. I would like to have an airport, I would like to have everything, but I definitely, definitely need a proper school for my children."

From the central square of the village of Ballesteros de Calatrava, you can see the airport. During the building of it, the now-deserted streets here were abuzz with expectation - people thought this huge project would bring jobs and a better life. Carmen Delgado, who lives here, says people were pressured to sell their land, and some of her family's fields were expropriated for the airport.

"Land is everything for us. If you have land you can have potatoes, tomatoes, animals, olives to make oil... And now? We've been robbed of our way of life, and for what?"

<bold>Listen to the full report on </bold> <link> <caption>Crossing Continents</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01l1dk9" platform="highweb"/> </link> <bold> on </bold> <link> <caption>BBC Radio 4</caption> <url href="http://bbc.in/qd934Q" platform="highweb"/> </link> <bold> on Monday 30 July at 20:30 BST or listen via the </bold> <link> <caption>Radio 4 website</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01l1dk9" platform="highweb"/> </link> <bold>.</bold>

<bold>Download the Crossing Continents </bold> <link> <caption>podcast</caption> <url href="http://bbc.in/rkM8x9" platform="highweb"/> </link> <bold>. </bold>