Weibo brings change to China

- Published

The breadth and nature of public debate in China has been drastically changed by the use of social media, but is it really just a poor replacement for real social change?

Beijing's recent floods were quickly followed by the resignation of the city's mayor.

The local government's handling of the crisis had faced criticism on social media, and the incident is a reminder of just how the internet has changed China.

The main reason for this transformation is <link> <caption>Weibo</caption> <url href="http://www.weibo.com/" platform="highweb"/> </link> , the Chinese equivalent of Twitter, which remains blocked in China.

The country's biggest microblogging service, Sina Weibo, now has 300,000,000 registered users, and is growing fast.

The Chinese authorities use a variety of means to control Weibo. Many of the posts criticising officials involved in a recent <link> <caption>student-led protest against the construction of a copper factory</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-china-18684895" platform="highweb"/> </link> in Shifang in Sichuan province were deleted, although by no means all - an indication of how social media has created new space for debate in Chinese society.

"Since Weibo, information in Chinese society has changed, it's become more transparent, more direct," says Wen Huajian author of China's first microblog novel, Love in the Age of Weibo, which was published via 500 posts on the micro-blogging site.

Mr Wen says sensitive topics like the frequent clashes between residents and local governments over forced demolitions are now widely debated.

"Web users will probably pay attention - and often the mainstream media will respond immediately, or sometimes the authorities too. In the past this was impossible."

Corruption is another topic, with a number of local officials having been forced to resign after being exposed online.

Weibo's ability to connect people has been used by campaigns to help street children, boycott polluting companies, even to ban the use of sharks' fins in soup.

It has also given ordinary people new opportunities for self-expression; not only can 140 characters in Chinese express more than in a western language, but Weibo has pioneered the inclusion of video and photographic images.

And Sina's innovation with images has helped it forge a symbiotic relationship with other online giants like <link> <caption>Youku</caption> <url href="http://www.youku.com/" platform="highweb"/> </link> - China's equivalent of YouTube - capturing the imagination of a tech-savvy young generation keen to post videos, both as citizen journalists and to show off their talents online.

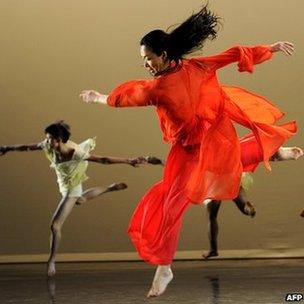

"Young people today express themselves, their emotions - unlike the older generation," says Jin Xing, a famous dancer and choreographer, whose own media career has received a huge boost from Weibo.

Chinese dancer and choreographer Jin Xing has used Weibo to promote her work

China's first publicly acknowledged transsexual, she had sometimes been featured in state media, but it was as a judge on a TV dance contest that she became a star, infamous for the blunt comments she posts on Weibo.

Now she hosts a national TV programme, and has a chat show watched widely online, focusing on social issues and relationship topics, many of them sourced via Weibo.

Jin Xing believes growing confidence in China's place in the world has made people more willing to open up in public.

"If you look at the microblogs you'll see how outspoken people are," she says. "About the government, society, legal issues, sexuality, stars, everything."

The Chinese authorities' attitude to this blossoming of self-expression is ambivalent. Official departments, from local governments to the police force, have opened Weibo accounts to communicate information to the public, and in some cases to seek feedback.

"We welcome people to take part in the debate," says Chen Cheng, who runs an official microblog for the city of Chengdu, capital of Sichuan province.

"As long as what they say is in accordance with the law, anything is allowed. If citizens discover something uncivilised in the city - rubbish, too much noise - they can tell us."

Yet the authorities have clearly been alarmed by the potential power of Weibo.

Last year, when a crash on one of China's new high speed rail lines killed more than 40 people the news was broken by eyewitnesses on Weibo and there was a <link> <caption>furious online reaction</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-pacific-14321787" platform="highweb"/> </link> to the handling of the crisis.

Senior railway ministry officials resigned, and prime minister Wen Jiabao made a public apology.

Mei Ke Li has won talent competitions for what she claims is the world's deepest female voice.

Similarly, when the police chief of the western city of Chongqing sought refuge in the US consulate in Chengdu this February, after falling out with his boss, politburo member Bo Xilai, the news leaked via Weibo posts about heavy security outside the consulate and the internet went wild with speculation.

But after Mr Bo was suspended from the ruling politburo, and his wife detained in connection with the killing of British businessman Neil Heywood, the government finally took action.

Weibo banned users from commenting on other people's posts for several days, and several users who posted speculation about a possible coup in Beijing were arrested.

Weibo has since introduced a new code of conduct for all users, and over recent months a number of people, including prominent journalists and intellectuals, have had their accounts shut down, prompting several leading academics to quit the service in protest.

Hu Xijin, editor of the Communist party-owned Global Times newspaper, argues that some control of Weibo is necessary.

"Weibo has some problems," he says. "Its descriptions are quite exaggerated, and many people intentionally say very extreme, very crass things in order to increase their number of fans or re-tweets."

Veteran Chinese blogger Michael Anti - who had his own blog shut down in 2005 - says it can bring social change, but does not pose a wider threat to China's political system.

"Social media has had a big impact on local corruption and made it hard for local governments to shut people's mouths," he acknowledges.

Yet he believes it also provides a convenient safety valve for the authorities, allowing people to express grievances without taking to the streets, or to go to Beijing to petition the central government.

Indeed, some experts say the authorities regard allowing online criticism as an alternative to serious political reform.

Michael Anti argues the censorship system is powerful enough to prevent Weibo from being used for overtly anti-government ends.

"If you want to write anything about opposition movement, about democracy, about protests, the keyword system will quickly find you and alert the local police.

"They will delete any sensitive account. They have made it impossible for nationwide dissidents to connect to each other," he says.

Internet expert Duncan Clark, of consultancy BDA, says the Chinese government's understanding of social media is more sophisticated than thought.

"They have devised things such as limiting the number of re-tweets and posts for a particular post or person."

He also believes social media provide the authorities with a simple way of monitoring the concerns of disgruntled groups in society.

But Michael Anti says social media have taught people that "freedom of speech is their birthright".

For veteran blogger Isaac Mao public frustration at internet controls, along with the sheer volume of information online, mean the current censorship system cannot last long.

State media editor Hu Xijin agrees things are certainly different: "The internet has changed the way lots of people think and work, and it's changed the attitudes of leaders and officials to public opinion.

"Weibo will continue to make space for itself," he says. "It definitely won't obey the government's management 100%."

And perhaps, most importantly, he concedes that Weibo is here to stay.

<bold>Duncan Hewitt is a writer for Newsweek magazine and lives in Shanghai. </bold>

<bold>He presents </bold> <link> <caption>It Started with a Tweet</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00v13g5" platform="highweb"/> </link> <bold> for the </bold> <link> <caption>BBC World Service</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/" platform="highweb"/> </link> <bold>. Listen via the World Service </bold> <link> <caption>website</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00v13g5" platform="highweb"/> </link> <bold> or download the </bold> <link> <caption>podcast</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/podcasts/series/docarchive" platform="highweb"/> </link> <bold>. </bold>

- Published16 July 2012

- Published9 March 2012