Warsaw Ghetto: A survivor's tale

- Published

Janina spent her early childhood in Kalisz, near the German border

Janina Dawidowicz was a nine-year-old girl when World War II engulfed Poland. As Jews, she and her family were soon driven into the Warsaw Ghetto, but she later escaped and remains one of its few survivors.

The extermination of the Jews of Poland began 70 years ago.

On the morning of 22 July 1942, Nazi soldiers marched the first group of 6,000 Jews held in the Warsaw Ghetto to the railway sidings, the Umschlagplatz, and put them on trains to the Treblinka gas facility.

Janina Dawidowicz, born in 1930, is one of the few people who lived in the ghetto and survived. She recalls the posters going up, ordering residents to report to the Umschlagplatz at 11 o'clock. Any one disobeying would be shot.

Many people, she says, lined up willingly. The Germans told residents that they were being sent to labour camps in eastern Poland where they could escape the misery. What is more, there would be handouts of free food.

"People were offered, I think, two loaves of bread, some margarine or some sugar if they reported to Umschlagplatz. Nobody could imagine that you were going straight into a gas chamber."

The first to go were those with the least power to resist - the old, the ill and the under-12s.

They included, from Janina's apartment, a fragile young woman called Rachel. She had once shown 11-year-old Janina her carefully-stored wedding outfit - a satin skirt and white blouse. When Rachel did not come home and Janina found her trousseau missing, she understood where Rachel had gone.

"Our landlord and landlady went next. They took all their kitchen stuff - pots and pans, large bundles tied up in a sheet, back and front, they could hardly walk. But they went. They waved goodbye and promised to write when they arrived in the East.''

The ghetto had been created as a holding pen for Jews in November 1940. The large Jewish population of Warsaw - a third of the city - was confined to a tiny area, where they were walled in.

They were joined by tens of thousands of Jews from other parts of Poland, Hungary and other German-occupied countries.

"You heard every language in the street," remembers Janina. "Yiddish, Polish, Hungarian, German."

Janina and her well-to-do family came from the city of Kalisz.

"I was an only child watched over very carefully by a nanny - frightfully well brought up - white gloves to play in the park! My mother had been to finishing school in Zurich... she could not boil an egg when the war started."

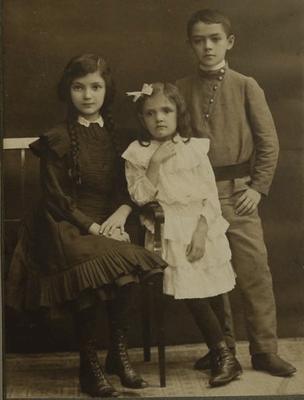

Janina's father Marek, here with his sisters, probably died at Majdanek

Janina and her parents squeezed into a tiny room, so damp that "I could write sums on the wall", and the sheets had to be dried before bedtime. They cooked on sawdust between two bricks, and fetched water from a communal tap. Food was bread mixed with sawdust and potatoes, rationed to 108 calories per day.

Janina's cousin Rosa had a lively toddler, who slowly starved to death. Like thousands of ghetto children, Cousin Rosa's little boy stopped walking, shriveled and died.

Desperate for a wage, Janina's father Marek got a job in the Jewish Law and Order service - the Jewish police.

The service was often reviled as a tool of Nazi policy, along with the Jewish administration. But at the time, the job seemed to hold out the best chance of keeping the family alive until the end of the war. Marek escorted cartloads of rubble out of the ghetto, and smuggled in small amounts of food.

Families tried fiercely to maintain a semblance of ordinary life between 1940 and 1942.

There were tremendous efforts to run community soup kitchens and look after orphans whose parents had starved to death, or died of the diseases that raged in the ghetto.

Many children like Janina attended illegal schools, risking instant execution for teachers and pupils if discovered.

There were choirs, physics lectures and cabaret shows to raise money for social services. Classes were held in every conceivable skill from cookery to paper-flower making.

The last family summer holiday was in 1939 (Janina is far left)

A symphony orchestra played at the theatre, complete with the stars of the music that all Warsaw had danced to before the war.

The Polish record company, Electro-Syrena, had been Jewish-owned and had produced hundreds of hits before 1939. Now, musicians and technicians alike lived in the ghetto - jazz men like the Gold brothers, Henryk and Artur, who'd run the famous Adria night club.

Janina and her mother, Celia, killed in 1942

All they had to do was outlast the war, people told themselves, and life would continue - perhaps not as before, but at least in some form.

"My mother, my grandmother would say: 'Oh, we need new curtains in the living room,'" Janina remembers.

"The carpets! We'll get Sophie and Stephanie in to give us a hand. No-one believed it would go on. France had fallen, but there was England and the USSR and America - there was a whole world. Of course it was going to end."

At the time, it was a reasonable wager. It was not until the autumn of 1941 and the German failure to march victoriously through the Soviet Union, that Nazi policy moved from the mass shooting of European Jews to comprehensive extermination.

Through July and August 1942, another 6,000 were sent from the ghetto to Treblinka each day.

By the end of the summer, more than a quarter of a million were gone, dead within hours of arrival at Treblinka.

Janina, as a policeman's daughter, was one of the few children alive.

"Our whole block of flats was empty. The father of the twins living above us threw himself out of the window when he came home and didn't find the children."

Janina now writes and lives in London

Janina's aunt was taken, then her grandparents. Then the police began being rounded up.

In the last weeks of the ghetto, in the winter of 1942, Janina's parents managed to smuggle her out to Christian Warsaw. As her father had police papers, he was allowed to escort lorries through the gates, so she slipped out with him.

In Warsaw, she was kept hidden by Catholic nuns, changing her name and concealing her identity.

Her parents stayed behind. She never saw them again. Janina thinks her father died in the Majdanek extermination camp. She does not know how or where her mother was killed.

After the war, Janina found one uncle. She returned to Kalisz, hoping someone else might reappear. She waited for over a year before giving up.

After two years in a children's home, Janina sailed in a ship full of emigrants to start a new life in Melbourne, Australia, where she got a job in a factory. It was in Australia that she managed, finally, to resume her education, and qualified as a social worker.

Homesick for Europe, she moved to London in 1958, where she began to write down her experiences in order to make sense of her life. She became a writer and translator, and has lived in London ever since.

<italic>Janina's autobiography, A Square of Sky, is written under her pen name of Janina David</italic>