Bamiyan Buddhas: Should they be rebuilt?

- Published

The destruction of Afghanistan's Bamiyan Buddhas in 2001 led to global condemnation of the Taliban regime. But the decision by Unesco not to rebuild them has not put an end to the debate about their future.

When the Taliban were at the height of their power in Afghanistan, leader Mullah Omar waged a war against idolatry.

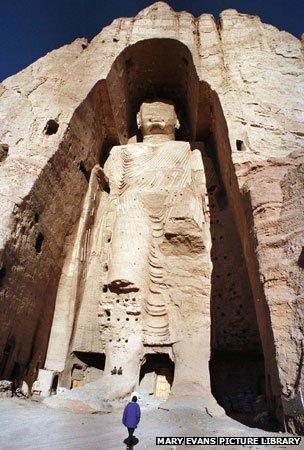

His biggest victims, in size as well as symbolism, were two standing stone Buddhist statues. Once the largest in the world - one measured 55 metres in height - they were carved into the sandstone cliff face of the Bamiyan valley in central Afghanistan during the 6th Century.

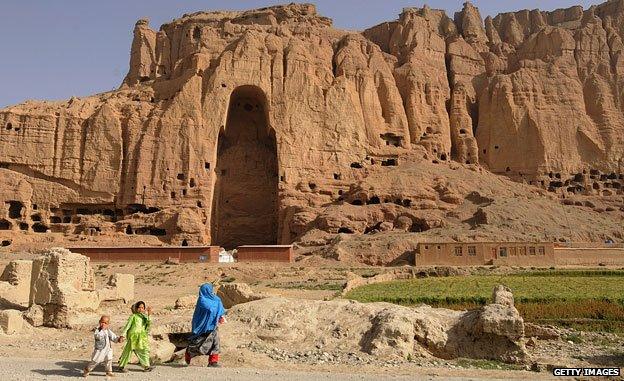

When the Taliban were overthrown in 2003, Unesco declared the valley a world heritage site and archaeologists flocked to it. What they found were two enormous empty caverns and a pile of debris littered with unexploded mines.

One of the Buddhas was 55 metres high

Since then, they have been surveying the rubble of the two stone structures to determine whether the Buddhas should be rebuilt.

The Bamiyan valley marked the most westerly point of Buddhist expansion and was a crucial hub of trade for much of the last millennium. It was a place where East met West and its archaeology reveals a blend of Greek, Turkish, Persian, Chinese and Indian influence that is found nowhere else in the world.

But last year, Unesco announced that it was no longer considering reconstruction. In the case of the bigger Buddha, it was decided there wasn't enough left to rebuild and though rebuilding the smaller one is possible, they said it is unlikely to happen.

Instead they are working with teams from Japan and Italy to secure the cracking cliff face and keep the cliffs and any of the remaining wall paintings that once covered the caves and niches intact.

But a German group of archaeological conservationists, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (Icomos), are still pushing for the Buddha to be rebuilt.

Bert Praxenthaler works alongside Icomos and since 2004 he has been working on the site to salvage any remaining fragments of the sculpture, some weighing up to 40 tonnes and putting them under a protective covering to preserve them as best he can.

He is interested in a process called anastylois which involves putting these fragments back together using a minimal amount of new materials.

"It's a jigsaw puzzle with missing links but with geological methods we can discover where those fragments have been before," says Praxenthaler.

The method has been used on the Parthenon and the Acropolis in Athens but it would be the first time it had been used to reconstruct a monument that was intentionally destroyed and arguments against reconstruction abound.

Not least is money. Rebuilding just the small Buddha would cost millions of dollars in a region that lacks basic infrastructure such as roads and electricity. It would require the manufacture or import of a huge amounts of metal which would have to travel along the dangerous road from Kabul.

"Of course the counter argument to that is that jaw-dropping sums of money are spent in Afghanistan every day," says Dr Llewelyn Morgan, author of The Buddhas of Bamiyan, a history of the sculptures. "This would be a drop in the ocean."

Still, Morgan says, there are more pressing issues that archaeologists need to look at in Afghanistan. "Bamiyan has a tendency to draw all archaeological resources to it," he says. "But in Afghanistan you are looking at an astonishing archaeological treasure trove."

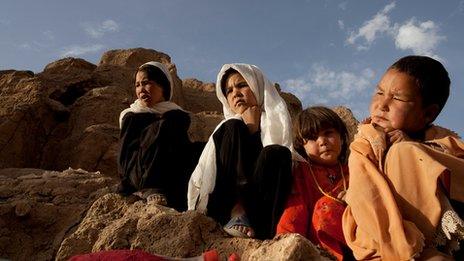

Families living in the valley remain impoverished

Looting is a very big problem and artefacts from around the country often end up in art markets in Pakistan. Morgan believes that resources would be better spent on creating an infrastructure to protect the breadth of Afghanistan's ancient treasures.

In a recent Huffington Post article, external he publicised the case of Chehel Burj, a medieval fortress in the mountains to the west of Bamiyan that is suffering from degradation.

"Give it time and illicit treasure hunting, earthquakes and old-fashioned freeze-thaw action will destroy more than the most single-minded iconoclast could ever dream of," he said.

Unesco are raising similar concerns and is funding the construction of a Museum for Peace at Bamiyan to promote awareness of Afghanistan's cultural heritage.

But whatever the reason, the Bamiyan Buddhas have captured the international imagination and ideas for what to do with the site still pour in from archaeologists, architects, artists and historians.

One that has gained quite a lot of attention is a proposal from Italian architect Andrea Bruno to construct a small underground sanctuary at the foot of the Great Buddha which would allow visitors to look up at and appreciate the immensity of the empty niche.

Bruno believes the niches should be preserved as a monument to the crime of their destruction. "It is a kind of victory for the monument and a defeat for those who tried to obliterate its memory with dynamite," he says.

He argues that reconstruction would be culturally insensitive. "Here the Muslims strictly oppose images - to recreate the Buddhas would be an insult even to non-Taliban Afghans. We must show good manners," he says.

But Praxenthaler believes that reconstruction is a matter of local pride for the Hazara people, Shia Muslims who were targeted and persecuted by the Taliban.

"It wasn't just a religious fatwa, to destroy all the idols, it was also an attempt to destroy the culture and the background and the pride of the people," he says. "The Hazara people appreciated that we were going to help them do something with their destroyed Buddhas."

He also says that reconstruction would enrich the local economy. His project has already employed over 50 people for salvaging and has also helped to train students from Bamiyan University in ancient stone-cutting techniques.

Access to where the statues once stood has revealed much about the region

"People are building homes and they are employed by us, they are working and they get a decent salary."

Llewelyn Morgan, who last visited the site a year ago, also found reconstruction to be popular among locals for whom the Buddhas were once a great source of income from tourists.

"The impression you get in Bamiyan is that they are almost too naively positive about the reconstruction of the Buddha," says Morgan. "I've spoken to people who would like to see it go up in concrete, which of course Unesco would never countenance."

But the reception to rebuilding in the rest of the country is unpredictable.

"Afghanistan is a great melting pot of cultures but the one thing many of them share is they are very pious," says Morgan.

"Though many clerics and religious leaders may not have agreed with the destruction of religious idols, building them again is an entirely different matter."

Bert Praxenthaler spoke to Outlook on the BBC World Service. Browse the Outlook archive or download a podcast.