What is it that really offends people about adverts?

- Published

A surprising number of people find charity advertising upsetting. What is it that really offends people about adverts?

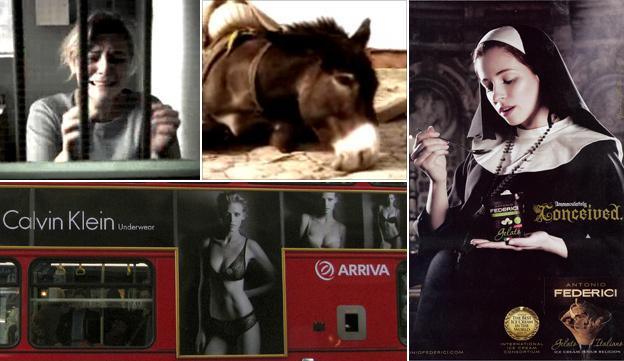

A donkey is trudging along a dusty road. "I work till I can't take another step," a voice over says. "So hot, so tired. I need water, shade, rest." The donkey's sad eyes confirm the message: "When the load is too heavy I fall. But I keep trying."

The emotive scene comes from a television advert for Brooke, an animal charity. Perhaps surprisingly, adverts for charities have been deemed some of the most offensive by the public in a new survey carried out by the Advertising Standards Authority.

The ASA report is revealing because it attempts to show what the average person - as opposed to someone who takes the time to complain - actually thinks.

Sixteen per cent of people said they had been offended in the past year by advertising. For children, the figure was 30% with sex, violence and frightening material the main reasons. The ASA defines offensive ads as those that anger people for being insulting, unfair or morally wrong.

A Kentucky Fried Chicken TV advert, which aired in 2005 and featured call centre workers singing with their mouths full of food, is the most complained about of all time. But it seems unrepresentative of the types of adverts that get members of the public hot under the collar.

Body image is an area that prompted a lot of spontaneous criticism, particularly for teenagers. Fifty-six per cent of 14-to-16 year old girls said advertising made them feel insecure about their appearance.

The donkey ad was joined in the charity section by a graphic advert for Barnardos in which a teenage girl is the victim of physical abuse. A slapping sound and moving camera are used repeatedly to dramatise her ordeal.

"Many participants felt that some charity adverts contained offensive content that went too far in seeking to make people feel uncomfortable or guilty, or used imagery that was considered too distressing despite being for a worthwhile cause," the ASA report states.

Most children spontaneously brought up charity adverts as having upset them or a younger sibling. Some stated their frustration at wanting to help the cause but feeling powerless to do so.

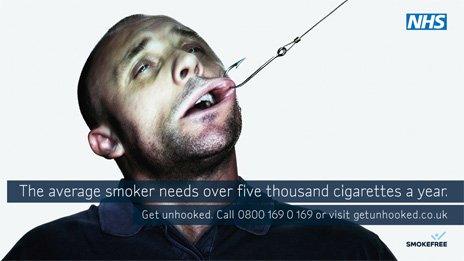

The charity areas most commonly cited as generally causing distress were international aid, animal welfare and child protection, while public information campaigns for drink driving, rape and smoking were also seen as upsetting.

Jasvir Kaur, director of Fundraising at the Brooke, says showing emotive scenes are necessary.

"We are aware of how difficult it is to see animals in distress or pain. However it is very important to highlight the desperate need for our work, in order to raise funds to help more working horses and donkeys overseas."

A series of NHS adverts showed smokers attached to fishing hooks

Lindsay Gormley, assistant director of marketing at Barnardos, defended the tone of the charity's advertising. "Barnardo's has a history of hard-hitting advertising. For the vast majority of viewers the messages are clear and as a result we see a substantial increase in people wanting to support Barnardo's work."

It's a difficult balance for charities, says Claire Beale, editor of advertising magazine Campaign.

"They have to make a small amount of money go a long way in a cluttered media environment. They have to make sure that in the one or two times that people see the ad, it registers. Hence you need to create a shocking or stand-out image.

As a result they have got more hard-hitting in recent years. There are risks attached, with such a provocative approach. As the ASA research appears to show, if it's too painful for people to watch they are likely to switch off.

Some were more annoyed by the model's pose than the nudity

When it comes to animals, the risks are even more acute due to Britain's sensitivity to animal cruelty, she says.

But Richard Alford, managing director of M&C Saatchi, disagrees.

"What people are complaining about is the issue not the advert itself," he says. So in the Barnardos ad it is the presence of child abuse that shocks people, in the Brooke advert it is the issue of animal cruelty. These charities are there to raise money to stop this kind of thing happening.

"How else can they advertise?" he asks.

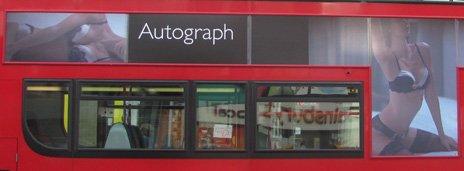

Sex and nudity is a traditional flashpoint. But the ASA survey suggests that attitudes are changing. Billboard posters of underwear or swim wear models used by Calvin Klein, M&S and H&M were deemed acceptable by most people. One M&S campaign did annoy some people, not for the nudity but for the suggestive poses of its model.

Most of those surveyed said nudity was acceptable if it was relevant - such as for lingerie - while sex could be excused if it was used cleverly. So a billboard advert for Durex Play that used the punch lines: "Do you like it loud? Are you ready to scream? Make some noise for the boys," was felt to be socially acceptable when it was revealed the advert had been displayed on the way to a Take That concert.

However those surveyed said the advert would not be appropriate for young teenagers.

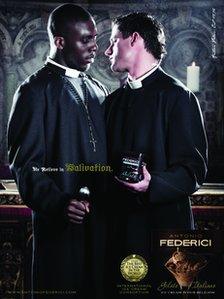

In contrast, using sex and religious imagery to sell ice cream offended many people. The adverts for Antonio Federici used a series of highly charged scenes involving priests and nuns. In one, a priest and nun appeared to be hell-bent on gaining carnal knowledge of one another. Many complained that the imagery was irrelevant to the product, and that using sex and religion to sell ice cream was gratuitous.

Federici ice cream ads caused offence

Matt O'Connor, creative director at Antonio Federici, argues that there is a long-established tradition of satirising religion in Britain.

"Poking fun at a Church which itself is in crisis shouldn't be something which is banned - and I say that as a Catholic myself. You'll see far worse watching Father Ted than in one of our ads.

"Our ads attracted a tiny number of complaints - one was banned on the basis of six complaints."

Public attitudes to sex and nudity have changed dramatically in recent years, Beale believes. No longer are people shocked by massive pictures of models in a bra and knickers on the side of a bus.

"It's becoming much more familiar because of access to sexual material on the internet. Tolerance levels appear to have risen," she says.

Today the issue appears not to be nudity but the sexualisation of children or the portrayal of unrealistic body shapes.

On the issue of body image, the report states: "The key concern was the portrayal of idealised body images, as these were thought to influence the self-image of children negatively, particularly young girls. For some, the fact that these images are often altered further exacerbated the problem, creating an impossible standard for children to live up to."

But Beale feels the question of body image is not just confined to advertising.

"It relates to the media in general," she says.

The ASA has highlighted offences thematically, such as body image or sex. But Alford believes the offence is often not so much thematic as something more banal. Loudness is a regular source of complaints as is bad dubbing or repetition.

In any case, there is a close link between offence and effectiveness.

"In a way success can often look the same as offence," Alford says. "It's intrusive, disruptive and memorable. In other words the offensive advert has elicited a response."