A Point of View: The enduring appeal of Sherlock Holmes

- Published

The fictional detective retains his grip on our imaginations, even in an age when we have lost faith in the power of reason to solve problems, says philosopher John Gray.

When the future seems more than usually uncertain and there's something troubling in the present, it's natural to look to the past. Could that be why the figure of Sherlock Holmes is once again in our minds?

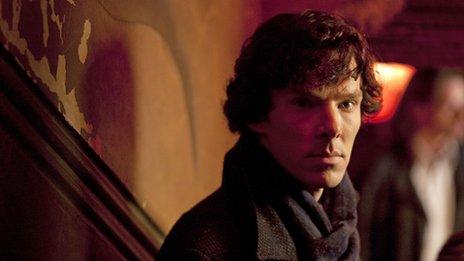

Brilliantly re-imagined in the new BBC series, Holmes uses the power of his luminous intellect to solve seemingly insoluble riddles. He is described as relying on reason, employing a science of deduction that enables him to explain events that have so far proved baffling.

Yet it's not the methods used by the fictional detective that fascinate us. It's the contradictory figure of Holmes himself.

Nearly 100 years on from the setting of the last of the Sherlock Holmes stories, in August 1914, we've witnessed a succession of failed experiments in using reason.

It's not just the collapse of communism followed by upheaval in free market capitalism - both of them systems based on theories that were supposed to be rigorously rational.

In everyday life, systems that were designed to be infallible - from the security software we install on our home computers to the mathematical formulae used by hedge funds to trade vast sums of money - have proved to be dangerously unreliable.

From the health service to care homes and prisons, institutions and services have been remodelled to obey principles of rational efficiency, with the result often turning out to be lacking in human sensitivity and at worst a mere shambles.

As a result of these failures, faith in reason has been dented. The idea that the intellect alone can be our guide in life is weaker than it has been for many years.

At the same time, Sherlock Holmes - a symbol of the power of intellect if ever there was one - is as powerful a presence in our imagination as he's ever been. It's a contradiction worth exploring.

It's not the science of deduction that gives Holmes his power over us, since he doesn't in fact use it. In The Sign of Four, Holmes declares: "I never guess. It is a shocking habit - destructive to the logical faculty." Yet the type of reasoning which Holmes uses in most of Conan Doyle's stories includes a good deal of guesswork.

We tend to think there are two types of reasoning:

deduction, where we move with logical certainty from general principles to a particular conclusion, as in "all swans are white, this is a swan, so this must be white"

and induction, where we move from particular observations to general principles, as in "all the swans that have ever been seen are white, so all swans are white"

Deduction is infallible as long as the premises are true, while induction yields probabilities that can always be falsified by events - the black swans that turn up when no one is expecting them.

The type of reasoning Holmes uses is of another, more conjectural kind - sometimes called abductive reasoning - that can't offer certainty or any precise assessment of probability, only the best available account of events. Importantly, this kind of reasoning can't be practised simply by following rules.

"When you have excluded the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth." Here Holmes is describing what he calls reasoning backwards - moving from the facts to an explanation of what has produced them by a process of elimination.

He does this in many of his cases, but it's not applying this rule that accounts for his astonishing feats.

If Holmes can identify an unlikely pattern in events, it's by using what Watson describes as his "extraordinary genius for minutiae". As Holmes tells Inspector Lestrade, the plodding Scotland Yard officer: "You know my method. It is founded on the observation of trifles."

Holmes notices things other people don't, and then - using a mental agility that involves creative imagination rather than the mechanical application of any method of reasoning - comes up with hypotheses he tests one by one.

It's not cold logic but a clairvoyant eye for detail that enables him to solve his cases. "I can never bring you to realise the importance of sleeves," he tells Watson, "the suggestiveness of thumb nails, or the great issues that may hang from a bootlace."

Holmes has the knack of knowing where to look, asking the right questions and crafting theories to account for what he has found.

What's striking is that Holmes relies on guesswork and imagination, supplemented and corrected by observation, as much as much on reasoning. A physician himself before he became a writer, Doyle tells us that he based the character of the detective on a medical professor he had known.

Holmes has an eye for detail

Like a good doctor, Holmes bases his inferences on evidence, but he reaches his conclusions by using his judgement. And he doesn't rely on his judgement only in the work of detection. He's ready to disregard legal rules when they seem to him unfair or out of place in the circumstances at hand.

As he puts it to Watson, "Once or twice in my career I have done more real harm by my discovery of the criminal than ever he had done by his crime. I have learned caution now, and I had rather play tricks with the law of England than with my own conscience."

With some of the qualities of a late 19th Century decadent, Holmes turns to detection as he does to his cocaine habit - to stave off boredom.

But he's not just playing at being a detective. He wants justice to prevail, and where necessary he's willing to flout the law in order to ensure that it does. The servant of reason, Holmes is also a romantic hero ready to defy authority in order to stand by his sense of morality.

At this point we're getting close to the contradictory sources of Holmes' power over the imagination. On the one hand he seems devoid of human feeling - "a high-functioning sociopath," as he describes himself in the new series.

At times he treats Watson - a stand-in for human beings in general - with something not far from contempt. But he also has genuine affection for his friend, and a deep sense of the random cruelty of the human scene.

In The Adventure of the Cardboard Box, published in 1892, he asks, "What is the object of this circle of misery and violence and fear? It must have a purpose, or else our universe has no meaning and that is unthinkable. But what purpose? That is humanity's great problem, to which reason, so far, has no answer."

Here Holmes is voicing an anxiety felt by many at the end of the 19th Century. With the advance of science, religion seemed to have been discredited. But the human needs to which religion answered - above all, the need for meaning in life - hadn't gone away. If anything, the need for meaning was felt more acutely than before.

Along with others at the time, Doyle found consolation in spiritualism - a movement with many of the functions of religion, but which claimed to be based on scientific evidence. That particular rationalist creed was followed by others, more militant and political in nature. All of them claimed to have solved "humanity's great problem" and to have done so by the use of reason.

Aside from a few relics of Victorian rationalism who find a curious comfort in Darwinism, most of us now accept that reason can't give meaning or purpose to life. If we're not content with the process of living itself, we need myths and myths very often contain contradictions.

Holmes is one such myth. Seeming to find order in the chaos of events by using purely rational methods, he actually demonstrates the enduring power of magic.

An exemplar of logic who lives by guesswork, a man who stands apart from other human beings but who is moved by a sense of human decency, Holmes embodies the modern romance of reason - a myth we no longer believe in, but find it hard to live without.

Can we learn to be reasonable without expecting too much of reason? Or will we blunder on, trying to remodel the world on rational principles that in practice produce chaos?