Ayn Rand: Why is she so popular?

- Published

A Russian-American writer who died 30 years ago is still selling hundreds of thousands of books a year, and this week one of her former devotees, Paul Ryan, became Mitt Romney's running mate in the US presidential election. So why is Ayn Rand and her most famous work, Atlas Shrugged, so popular?

It's 1,200 pages long and was panned by critics when it was published 55 years ago.

Yet few novels have had an impact as enduring as Atlas Shrugged, a dystopian allegory in which captains of industry struggle against stifling regulations and an over-reaching government and one by one close down production, bringing the world economy to its knees.

Rand's philosophy, which she called objectivism, tapped directly into the American ideals of freedom, hard work and individualism. In novels like Atlas Shrugged, and her non-fiction like The Virtues of Selfishness, Rand argued for the removal of any religious or political controls that hindered the pursuit of self-interest.

As she explained in a 1959 television interview, external: "I am primarily the creator of a new code of morality which has so far been believed impossible - namely, a morality not based on faith, not on emotion, not on arbitrary edicts, mystical or social, but on reason."

She believed, she added, that man's "highest moral purpose is the achievement of his own happiness, and that he must not force other people, nor accept their right to force him, that each man must live as an end in himself and follow his own rational self-interest."

Atlas Shrugged is her magnum opus, set in an undated American future, although it is reminiscent of the 1950s. The strike by millionaire tycoons is orchestrated by the Christ-like figure of John Galt, who towards the end of the novel makes a 60-page speech that took Rand two years to write.

Her voice and ideas are clearly present in the noble characters of Galt, railway heiress Dagny Taggart, copper magnate Francisco d'Anconia and steel tycoon Hank Rearden.

This quartet are idealised figures, capitalist high-fliers who must defeat Rand's "looter" enemies - unions, lobbyists, government officials and any supporters of altruism and welfare.

Rand herself saw this struggle play out in the most traumatic way.

Born into a Jewish family called Rosenbaum in St Petersburg, she was just 12 when she witnessed her father's pharmacy being seized by the Bolsheviks.

"Many scenes from Atlas Shrugged are transmuted and re-enacted scenes from Rand's childhood," says biographer Anne Heller. "When the government comes to take Hank Rearden's patent from him and he refuses, that is what she wished would have happened to her father."

She never forgot that injustice and humiliation, says Heller, author of Ayn Rand and the World She Made, even when she arrived in the US eight years later.

"They [her family] were told it was for the good of the people, but she saw that people who worked hard like her father had to sacrifice years of hard work for people she thought had not educated themselves. She saw the same forces at work in the US when FDR's New Deal got a foothold."

Her novel, The Fountainhead, about an architect, was a word-of-mouth success and made into a film starring Gary Cooper.

It drew a committed group of supporters to Rand, some of whom gathered every Saturday at her New York apartment to read extracts from her next book. Among them was an economic forecaster called Alan Greenspan, who became her close friend and eventually chairman of the US Federal Reserve.

Despite this dedicated following, reviews of Atlas Shrugged in 1957 were not favourable, and its message united both left and right in condemnation. Gore Vidal described it as "almost perfect in its immorality".

But this didn't stop it from becoming an international bestseller, as millions were drawn to her central message of individualism and unfettered capitalism, even if they didn't buy into her whole philosophy. In the 1990s, a survey by the Library of Congress named Atlas Shrugged as the most influential book in the US, after the Bible.

And more than 50 years after publication, sales are booming. According to Nielsen BookScan, more than 300,000 copies were sold in the US in 2009, pushing sales for all her works past the half-million mark that year.

The extent of her influence was demonstrated this week when Paul Ryan joined the Mitt Romney ticket, although he has now distanced himself from her work.

In 2005, Ryan told the Atlas Society, external how Rand "taught me quite a bit about who I am and what my value systems are". But earlier this year, he told the National Review, external that as a Catholic he rejected her atheism.

Beyond politics, the novel also had an impact in Silicon Valley, where entrepreneurs identified with its emphasis on heroic individuals and their work ethic. Some have named their companies or their newborn children after the author or her characters.

Rand has a following in India

Rand's popularity is not confined to the US, however, with healthy book sales in the UK, India, Australia, Italy and South Africa.

But she speaks most directly to American conservatives, says Timothy Stanley, a British historian at the University of Oxford who writes about US politics for the Daily Telegraph.

"American Conservatism is fundamentally about the relationship between the individual and the community, about jealously protecting the individual's liberty.

"British Conservativism is about the Queen, the Anglican Church and rituals like tea. It's less about the economy or your relationship with government, so there is very little in Ayn Rand that they could identify with."

Paul Ryan genuinely fell out of love with Randian ideas, says Stanley, and that comes with age.

"Atlas Shrugged was a very exciting book to read when you're young but then you grow up and get a family and develop a relationship with God.

"Rand teaches you that the individual is in complete control of their life and adolescents are terrified of being told what to do.

"She tells students that when they leave college they will work for liberals who will take their taxes and don't know anything. She massages the egos of juveniles."

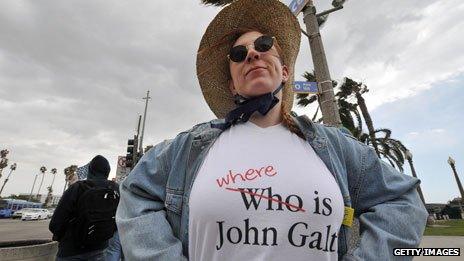

The emergence of the Tea Party - a wing of the Republican Party which favours a shrinking of the state - appears to be driving her recent resurgence. John Galt is often referred to on placards and T-shirts.

"She's become a more dominant influence than she's ever been and that's bad because she's made it cool to be selfish. It's bad for the people outside her favoured elite, the 99%. And it's bad for the morality of the US," says Gary Weiss, author of Ayn Rand Nation: The Hidden Struggle for America's Soul.

In Rand's later life, her followers turned away from her - some were appalled to learn she had been conducting a 14-year affair with her associate Nathaniel Branden, apparently with the consent of her own husband and Branden's wife, Rand's close friend Barbara.

Others were put off for other reasons. One former acolyte, Jerome Tuccille, recalls supporters being "robotic" in their admiration and after two or three years, he turned his attention to less "flawed" libertarian causes.

"She could give a great speech but she was very harsh and very vindictive to anyone who challenged her. She wasn't open to debate but trounced them as irrational, altruistic and hopeless.

"Rand's world was black and white. You are either all good or all bad. Her world is a good fictional representation but it doesn't work in reality in terms of human beings."

This difficulty was most clearly illuminated in Rand's final, lonely years when she claimed social security - an act her critics saw as inherently hypocritical but others said was her due.