Paralympics 2012: Is it OK to call the athletes brave?

- Published

Before the Paralympic Games started, the media earnestly discussed the words that should and shouldn't be used. It can be a curious area.

One thing that tends to draw disabled people together is the subject of what people do and don't want to be called.

At the Paralympics stadiums and arenas, the commentators you hear on the public address system refer only to the technical terms, sounding a bit like playing a game of battleships: T54, C3, S6.

The first letter of this refers to the event - like T for track, C for cycling or S for swimming. The number refers to the level of impairment where usually the lower numbers are most disabled, and higher numbers least. I've yet to hear an official shouting something like "she's got spina bifida".

Earlier this year, the British Paralympic Association (BPA) put out a Paralympics language guide, external and media organisations covering the Games have had meetings and have drafted documents about it to make sure they get it right when reporting.

Mostly this is about Paralympic etiquette - apparently we shouldn't refer to someone as a "former Paralympian" for instance. If they've been a Paralympian they're always a Paralympian. But much of it is about respect for people and their achievements.

In the park on Saturday, I wandered around asking people what words they would use to describe the athletes. Jacqui and John Voyce, from Winchester, had brought their nine-year-old twins along.

Between them they agreed that the athletes were both brave and inspirational. John hesitated though.

"I don't want to say inspiring," he says. "I'm in the forces and a lot of the paralympic athletes are also ex-forces. They say they don't want to be referred to as inspiring because they are what they are and they're just doing it."

The sensitivity around these words is particularly interesting around Paralympics time.

This week we're seeing elite disabled athletes running, swimming, shooting arrows, playing tennis and more. They are certainly inspiring - as are all athletes, but decades of low expectations about disabled people means that they have often been classed as heroic just for going down the shop to buy a pint of milk.

In some circles, words that patronisingly elevate disabled people to a superhuman level they don't really deserve are seen as more damaging and life-limiting than good old-fashioned playground taunts.

Actor Jamie Beddard, who was lead artist in Breathe, a mixed ability performance on Weymouth beach which opened the Olympic venue in July, says: "Most epithets such as inspirational, brave, etc, are used as a means of separating us [the disabled] from them [the non-disabled] and have all kind of 'there but for the grace of God go I' notions."

Perhaps overly aware of the issues of language, while listening to BBC Radio 5 live, I heard a sports presenter refer to a swimmer as having had a "brave" performance.

Did he mean braver than average, brave to have got in the pool, or was there something about the swimmer's performance that really was wrenchingly physical and tough to achieve? I was left believing he meant the latter and wasn't being at all condescending.

Quentin Hull is a sports commentator for ABC, Australia's official Paralympic broadcaster, doing his second Games.

"Those phrases that we're probably told to hold back on like inspirational, all those words just drip off your tongue during a paralympic Games because of the human achievement mixed in with the athletic achievement," he says.

"There's a bit more of a purity to the fact that the human race battles to succeed no matter what the cost because it's a bit more visible and easy for someone to fathom the effort put in when they see Oscar Pistorius with two prosthetic legs.

"If you see eight guys running in a race at the Olympics, all with two arms and two legs running fast, it's very hard to work out their achievement story because the timepiece only shows you the athletic achievement, it doesn't show the human achievement."

But interestingly the athletes don't necessarily know the language rules. After a match, one GB athlete said: "The crowd went mental."

With over 6,000 people cheering her on, you can perhaps appreciate why she reached for the word "mental", especially as it's so often used in a casual manner away from the arena of mania and schizophrenia.

But it's one of the disability words that I choose to avoid using in that way, like its linguistic friend "psycho". Life experiences tend to dictate your own personal dictionary.

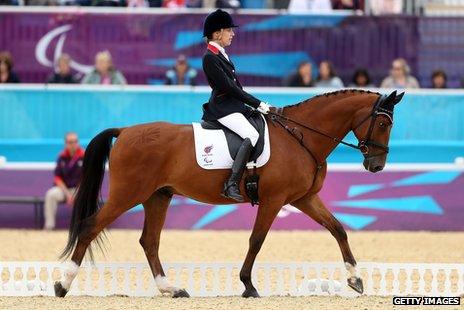

On Sunday night, Channel 4's dressage commentary referred to Sophie Christiansen's "involuntary movements".

A commentator referred to Sophie Christiansen's "involuntary movements"

How do we feel about commentary on cerebral palsy spasming? The British Paralympic Association would rather you didn't dwell on people's disability but, if it's visible on your TV screen and could be seen by the audience as potentially destroying those nice clean body lines or whatever it is that dressage experts might talk about, is it OK as a bit of analysis?

I'm not sure that debate has ever properly happened without a room full of fearful television executives nodding as they scribble notes and try hard to get their heads around it.

The fear factor is high and, in my long experience of these things, can sometimes stop programmes going out or disabled contributors being used on air because some people just really badly don't want to get it wrong.

Paralympic cyclist Jon-Allan Butterworth is a former RAF serviceman

People needlessly go red and start apologising if they say the word "walk" in front of a wheelchair user on your average day in Britain. And this all occurred shortly before GB's man David Weir won the 5000m in such an impressive style that his name started trending round the world on Twitter and he was "mentioned" by Olympic runner Usain Bolt.

If disabled people previously only found common ground on negative things - like hating being called special - perhaps these widely covered, jaw-dropping Games will present some collective positives to latch on to.