Beijing revisited after half a century

- Published

Bicycles dominate a Beijing street in 1965

Returning to Beijing after nearly 50 years sparks recollections of a China long gone, and the memory of one very special meeting.

The circumstances of my first visit to China were curious, to say the least.

A delegation of 25 journalists including a handful of Western reporters like myself had been chosen by the Communist authorities to report on the return home to China of a former warlord called Li Zongren.

General Li - although I personally had never heard of him - was famous for military campaigns during upheavals inside China during the 1920s, and again during the war against the Japanese in the 30s and 40s.

The general had, in fact, been acting president of China for a very brief moment during the period of political turbulence just before Mao Zedong emerged as leader in 1948.

He had escaped to the US and lived in exile there like many members of the former regime. Sick and old, he now wanted to return home to die, like any good Chinese, and a secret handover was arranged in Geneva.

So, on a cold, sunny Sunday afternoon in late September 1965, I found myself at a news conference followed by a reception in Beijing in the Great Hall of the People, rubbing shoulders with the entire top Chinese nomenklatura who had gathered to welcome the famous former warlord.

Zhou Enlai welcomes Li Zongren

I remember recognising Chairman Mao's brilliant number two, Zhou Enlai, an unforgettable face, and the burly Chen Yi, the powerful general who was acting foreign minister.

Pu Yi, emperor and, later, gardener

Also Peng Zhen, the Mayor of Beijing, shortly to be purged as the Cultural Revolution surged ahead and the infamous Red Guards caused mayhem all over the country.

I was even introduced briefly to a sad-faced, bespectacled old man who was pointed out to me, standing there drably dressed in dark blue fatigues in a corner of the vast reception room.

He was Pu Yi, the last Emperor of China. Pu Yi, last in line of the Qing dynasty, had succeeded briefly to the Dragon throne while still a toddler, and was forced to abdicate at the age of six.

After an eventful life, which had included a period of captivity in Russia, they told me, he was now employed as part-time literary editor and part-time gardener by the new Communist masters of China.

Beijing today bears little resemblance

To refresh my mind about what turned out to be perhaps three of the most exciting weeks of my entire life, I have been looking at my diary notes for 1965 and viewing for the first time in decades an hour of 8mm colour film I shot - despite the worried glances of our official minders - as we moved around Beijing and, later, around some of China's other major cities.

I dutifully filmed a spectacular stadium performance by tens of thousands of schoolchildren performing synchronised gymnastics and holding up coloured cards glorifying the People's army and vilifying the American "aggressors" in Vietnam.

I saw more than a million people march past the "Great Helmsman" Mao Zedong himself, wearing his signature grey padded uniform, high above us on the saluting platform at the Southern gate of the Forbidden City. A huge, sleek but menacing missile - a Western military expert later told us it was only a mock-up - featured among the apparently endless floats and marchers that paraded for hours past the VIPs and the regimented crowds of students and workers in a skilfully choreographed spectacle.

David Willey on life in China in 1965

What impressed me most was the lack of motorised traffic. We Hong Kong journalists had our dedicated bus and official minders, and there were plenty of official Russian-built limousines for the VIPs, but most Chinese went around on foot, or on bicycles, or crammed into the back of trucks, or in trishaws - that ingenious man-powered combination of rickshaw and tricycle which has in the 21st Century spread even to the streets of Manhattan and London.

A few ageing American Buicks and Chevrolets imported before the Communist takeover 17 years before, had survived with the help of cannibalised spare parts. But when the well-drilled National Day Anniversary crowds had dispersed, the wide expanses of Tiananmen Square were mostly empty. I frequently saw Chinese labourers often carrying what seemed to me impossibly heavy loads on yokes on their shoulders, coolie style.

Later, during an excursion along the Yangtze river, we saw what was planned to be one of the world's longest railway bridges under construction. The river delta was a hive of human activity. I saw little mechanisation. It all reminded me of scenes painted by Renaissance artists during the construction of the great architectural landmarks by the Popes of 16th and 17th Century Rome.

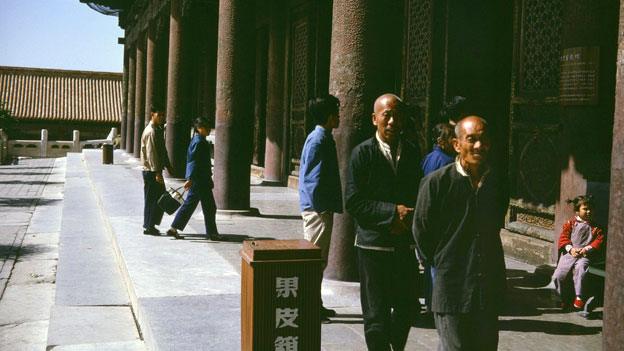

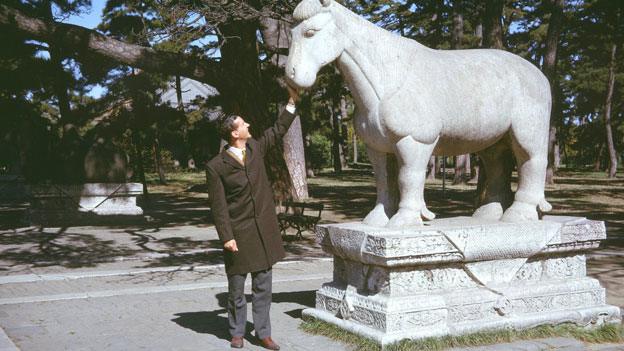

A quiet museum-like atmosphere reigned in the empty courtyards of the Forbidden City in 1965 - 47 years later it throngs with tourists - mostly Chinese - and gesticulating tour guides

Plain mass-produced clothes, such as the blue jacket named in the West after Chairman Mao, were ubiquitous half a century ago, almost like a uniform for civilians

Men in military uniforms were commonplace on the streets of Chinese cities seven months before the start of the Cultural Revolution, and still are...

... though the styles observed by David Willey are now the stuff of fashionable kitsch memorabilia stores

The red scarves of pioneers - politically correct cub scouts or girl guides - are also still a common sight

The Cold War was in full swing in 1965 - this display on the streets of Beijing is supposed to be the remains of a US U2 spy plane, which China claimed to have shot down

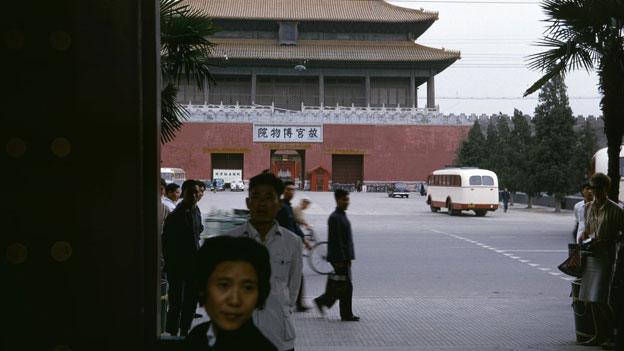

Arriving from Hong Kong, David Willey was impressed by Beijing's largely traffic-free streets - a few vehicles here had delivered a modest number of tourists to the Forbidden City, but bicycles were more common

No cars, buses or lorries are visible on the road that runs round three sides of the Forbidden City's perimeter

Some of Beijing's historic buildings were the worse for wear in 1965

Now the ancient palaces boast shiny coats of coloured paint

The country that greeted David Willey in 1965 is unrecognisable to him today

Now dozens of bullet trains pass over that bridge every day reducing the journey time from Beijing to Shanghai to only four hours, from the 24 hours it took back in 1965.

In Manchuria, in China's industrial north, we visited heavy industry, a steel factory and a transformer plant. The scene inside the steel rolling mills reminded me of pictures of Britain's 19th Century industrial revolution. In the South we saw heavy barges toiling along the Pearl river, all of them human-propelled. Impressive but back-breaking for the oarsmen.

Returning to Beijing after nearly 50 years, the city I remember is almost unrecognisable. The road traffic is unceasing despite an efficient underground system. So many cars compete for space on the road that the licensing authorities have recently had to restrict the purchase of new vehicles by private individuals.

Ordinary Chinese have abandoned their drab fatigues in favour of modern Western styles. Their ever expanding capital city boasts not only some of the most iconic examples of modern building technology created by internationally famous foreign architects, but also a forest of indifferent high rises.

At a private dinner party in the bustling business district on the 56th floor of a brand new skyscraper, I gaze in wonder at the glittering spectacle of Beijing by night. The new China Central TV headquarters rises in front of us. Imagine two huge intersecting glassed-in arches with part of their supporting structure daringly removed so that they appear partly to float in space.

I mention to my Hong Kong-born hostess that is my first visit since the curious episode of the return home of Gen Li Zongren.

"Oh, I remember him well," she replies. "You know he did die shortly after his return.

"It was all part of a propaganda stunt by the Chinese government to encourage other former Kuomintang Nationalists to return from exile. In fact I have a book all about it."

She pulls out a slim volume from her library. And there is a familiar picture of the general amid his friends taken on that long ago September afternoon in the Great Hall of the People, when I rubbed shoulders for the first and only time in my life with the top leaders of the China's Communist revolution - and shook hands with the Last Emperor.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent:

BBC Radio 4: A 30-minute programme on Saturdays, 11:30 BST.

Listen online or download the podcast

BBC World Service:

Hear daily 10-minute editions Monday to Friday, repeated through the day, also available to listen online.

Read more or explore the archive, external at the programme website, external.