Nikola Tesla: The patron saint of geeks?

- Published

Fans have rallied to buy the lab of inventor and electricity pioneer Nikola Tesla to turn it into a museum. But why do so few people appreciate the importance of Tesla's work?

Lots of people don't know who Nikola Tesla was.

He's less famous than Einstein. He's less famous than Leonardo. He's arguably less famous than Stephen Hawking.

Most gallingly for his fans, he's considerably less famous than his arch-rival Thomas Edison.

But his work helped deliver the power for the device on which you are reading this. His invention of the induction motor that would work with alternating current (AC) was a milestone in modern electrical systems.

Mark Twain, whom he later befriended, described his invention as "the most valuable patent since the telephone".

Nikola Tesla was increasingly eccentric in his later years

Tesla was on the winning side in the War of the Currents - the battle between George Westinghouse and Thomas Edison to establish whether AC or direct current (DC) would be used for electricity transmission. But as far as posterity goes, time has not been kind to Tesla.

Born in what is now Croatia to Serbian parents, he moved to New York in 1884 and developed radio controlled vehicles, wireless energy and the first hydro-electric plant at Niagara Falls. But he was an eccentric. He believed celibacy spurred on the brain, thought he had communicated with extraterrestrials, and fell in love with a pigeon.

Over recent decades he has drifted into relative obscurity, while Edison is lauded as one of the world's greatest inventors.

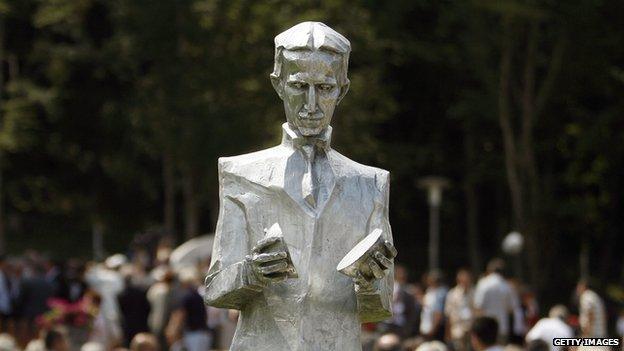

But his memory is kept alive by legions of "geeks" and science historians. A Tesla museum on the site of his former laboratory is being planned after a crowdfunding project orchestrated by The Oatmeal cartoon site. It raised more than its target of $850,000 - which will be matched by the New York state authorities - in the first week. The total is now well over $1m.

Quirky fan tributes, external to Tesla have sprung up online.

David Bowie played Nikola Tesla in 2006 film The Prestige

A possible biopic starring Christian Bale and directed by Mike Newell is doing the rounds of the Hollywood rumour mill.

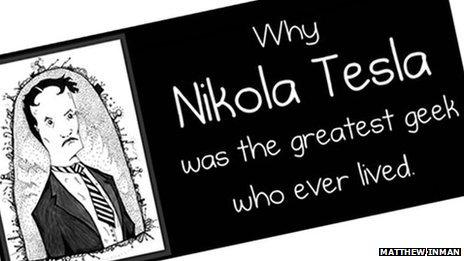

The crowdfunding idea was the brainchild of Matthew Inman, the cartoonist behind The Oatmeal, external. Inman heard of the museum appeal and decided to help. Tesla is a hero, he argues who "drop-kicked humanity into a second industrial revolution".

His triumph was his work on systems for AC.

Edison's DC worked well for lighting but could not be used to transmit electricity for long distances.

AC was backed by the Westinghouse Corporation. Its voltage could be stepped up and down easily so it could be transported over long distances at high voltage, using a lower current and therefore losing less energy in transit.

The stumbling block for AC had been motors. But Tesla's design for an induction motor and transformer cleared the way.

It's enough to justify a fair measure of adulation, says Inman.

"It's his absolute commitment to being a geek. He's more like Steve Wozniak than Steve Jobs. He's this insane mega genius."

Despite Tesla's lack of popular culture presence, the War of the Currents reads like the stuff of Hollywood film.

Edison tried to discredit the rival technology as dangerous. He organised public electrocutions of animals - including an elephant - and secretly funded the development of the first electric chair, which he believed showed the dangers of AC.

The publicity campaign was not enough to overcome the clear advantages of AC.

Long-distance powerline systems like the UK's National Grid, transmitting electricity at 400,000 volts, are a testament to Tesla and his fellow AC advocates.

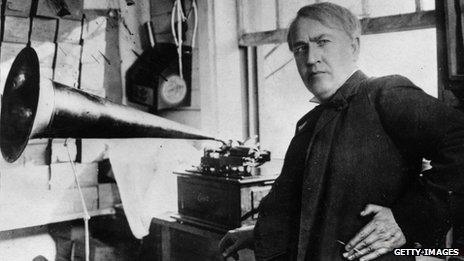

Tesla and Edison were very different types of genius, says Marc Grenther, chief curator of the Henry Ford Museum in Michigan.

Tesla liked to conceptualise and work things out in his head. He cared more about the idea than its practical exploitation.

Edison started with the commercial potential and would repetitively test things out with physical investigation.

Thomas Edison tried to discredit Tesla's rival technology

"Tesla was more cerebral. It was like he inhabited the world of philosophy," Grenther says. "Edison was more hands on, it was seat of the pants stuff."

If they were both greats, why is it that Edison's reputation has grown while Tesla's has fallen away?

How we remember scientists isn't always fair, suggests Sir John Pendry, professor of physics at Imperial College London.

Sir Joseph Swann invented a lightbulb in Newcastle at the same time that Edison made his key invention in New York. But it is Edison who gets the credit.

It is not enough to have ideas, says Will Stewart, fellow of the Institution of Engineering and Technology. "As an engineer you have to understand what is practical. The hard thing is whether it can be done with the technology you can get your hands on."

Tesla was "brilliant" but would relentlessly pursue an idea like wireless energy transfer, even when it appeared unachievable to others. Edison on the other hand was a forceful character who could win people over and turn ideas into a product.

"It's the nature of history that a few people get credited or debited with everything," Stewart adds.

The Oatmeal website's cartoons champion Tesla and his achievements

Today it's Albert Einstein not Hendrik Lorentz who is best known, even though some science historians see Einstein as having essentially tied up a series of threads Lorentz had first worked on.

There's also the intangibility of what Tesla did, says Grenther.

Edison's lightbulb, the mass market car developed by Ford, or the computing products of Bill Gates and Steve Jobs were things people could touch or see.

Tesla has a unit of measurement for magnetic field named after him. He is celebrated in Croatia and Serbia, where a power plant is named after him. Science "geeks" worship him. He has a rock band and a crater on the moon named after him. Then there's the range of electric cars. His is the classic cult following.

He died a penniless recluse in Suite 3327 of the New Yorker Hotel. The mainstream cultural fame of an Einstein or an Edison still eludes him.