NFL safety: Is American football too violent?

- Published

- comments

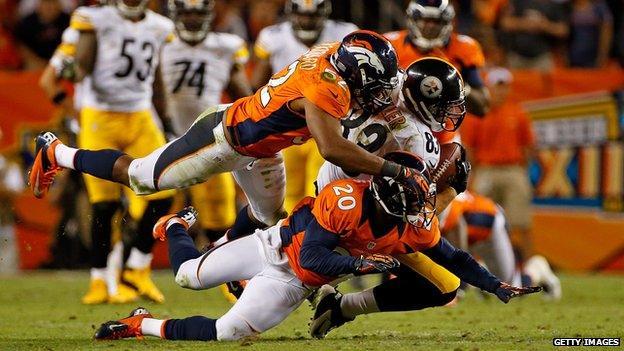

Fans are attracted to football's big hits, but some are troubled by the long-term consequences

Some American football fans are worried that the National Football League is too brutal to be enjoyed. Can the sport change course?

Charlie Camosy is a big fan of American football.

"It's a great combination of raw caveman strength and gladiatorial combat and the most complicated chess match you can ever imagine," he says, noting that this time of year - when football returns - is one of his favourites.

But Camosy is also a professor of Christian ethics at Fordham University in New York. And this year, he's feeling more and more conflicted about watching the sport he loves when he knows it can be so dangerous.

"Even though I'm excited for the start of the year, we need to be honest about the fact that football is a violent sport, and many things that people like about it, including me, is the violence. It's not just violence in the abstract, it's people's lives who are tremendously impacted by this." says Camosy.

Football has always been a brutal sport: in the early days of the game, President Theodore Roosevelt threatened to shut the college programme down unless the young men from Harvard, Princeton and Yale stopped dying on the field.

One of the National Football League' s most memorable games was the 1985 match between the Washington Redskins and the New York Giants, when Giants defensive player Lawrence Taylor tackled quarterback Joe Theisman with such force that Theisman's leg snapped in two, bone and blood visible on the field.

"Football and violence is nothing new whatsoever," says Frank Deford, sports commentator for National Public Radio and author of Over Time: My Life As a Sports Writer. In the past, that violence has ebbed and flowed as rule changes sought to limit the damage. "It's gone back to a peak again, and the question is whether you can correct the game," he says.

The current state of professional football means that the violence is more impressive to watch - and has more long-lasting consequences.

"We have a better idea of how the story ends now," says Will Leitch, a contributing editor at New York Magazine. The life-long football fan wrote an article earlier this month called "Is Football Wrong?, external"

His article echoes recent blog posts made by writers like Ta Nehesi Coates, external and Andrew Sullivan, external. In each case, the arguments are similar: the hits are getting bigger and harder, and the evidence we have about the long-term effect on player's brains are getting harder to ignore.

"We're creating, essentially, missiles of people's bodies banging into each other in the most dramatic ways. We haven't seen the people with 300lb (136kg) bodies who can run the 40-yard dash in 4.6 seconds," says Camosy. "That kind of force has never existed in the human body before."

Mounting evidence shows that the damage caused by repeated concussions can have lasting health consequences for American football players. These men are more likely to die from diseases caused by damaged brain cells, like Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or Alzheimer's disease, according to a new study in the journal Neurology., external

Medical experts suspect repeated head trauma can lead to mental illness and suicide, and there have been a rash of former NFL player suicides in the past.

Shortly before committing suicide last year, Dave Duerson, a former player for the Chicago Bears, sent a text message to his family requesting that his brain be donated to a facility that researches football injuries.

Junior Seau committed suicide in 2012. His death has not been linked to brain damage, but triggered safety questions

"He was one of my favourite players," says Leitch. "The idea that he was mush at the end, the way he committed suicide to make sure his brain could be preserved...It's hard to then be like 'Yeah, jack em up! Huge hits!'"

But the huge hits are still drawing lots of fans.

The first Sunday Night Football game of the 2012-2013 season brought in record ratings this week, with almost 25 million Americans tuning in to watch the Denver Broncos defeat the Pittsburgh Steelers. According to TVLine.com, external, that number represents a 7% increase over last year and the best rating for a regular season football game in 14 years.

For its part, the National Football League is doing what it can to stem the damage done by the sport. Recently, the league donated $30m (£18.7m) to the National Institutes of Health to study brain injuries.

"Our commitment is to keep pushing the envelope and be one of the leaders in health and safety research," says Clare Graff, the senior manager of corporate communications at the NFL. She points out that head injuries are an issue of concern for other sports, not just football.

At the same time, the NFL is constantly revising rules to try to limit the long-term damage done to players, and does so knowing that its rules and safety regulations are often adopted by youth and college programs.

"We want to set the standard and we take that responsibility seriously," she says.

Whether or not they can make the game safe for kids, not just for professionals, may be what eventually determines American football's fate.

"What you are hearing for the first time is 'I don't want to see my child playing football'," says NPR's Frank Deford.

"I don't think we've come to the point where I've heard anyone say I'm not going to a professional game."

That's something both Leitch and Camosy understand all too well. Both men will be tuning into the football season this year despite their reservations.

"I'm going to watch football but it's almost with a sense of sadness this year - a growing sense of sadness," Camosy asks.

"How long can I watch football and still keep my soul?"

- Published4 May 2012

- Published7 June 2012

- Published29 November 2011