How often do plane stowaways fall from the sky?

- Published

Police are investigating whether a man found dead on a west London street was a stowaway who fell from a plane. Just how often does this happen?

No-one saw the body fall from the sky on to Portman Avenue.

A few neighbours thought they heard something, a thud or a loud bang. But not a soul was around to witness a man hit the pavement of this quiet residential street in Mortlake, south-west London, early on a bright September Sunday.

Police say the death is being treated as unexplained. But early media reports all shared the same assumption - that he had stowed away in the landing gear of a plane flying to Heathrow, less than 10 miles away.

"He must have come down pretty much vertically to miss the parked cars," says John Taylor, 79, who heard a thump from his home across the street in this placid, affluent suburb. "I expect he was dead already. Poor chap must have been desperate."

Flowers mark the spot where a body was found in Mortlake

It is not the first incident of this kind on the Heathrow flightpath.

In 2001, the body of Mohammed Ayaz, a 21-year-old Pakistani, was found in the car park of a branch of Homebase in nearby Richmond. Four years prior to that, another hidden passenger fell from the undercarriage of a plane on to a gasworks close to the store.

Others turned up at Heathrow itself. On 24 August, just 16 days before the discovery on Portman Ave, the remains of another man were found in the landing gear bay of a Boeing 747 after it touched down from a 6,000-mile flight from Cape Town. The bodies of two boys, thought to be as young as 12, were discovered in the undercarriage of a Ghana Airways flight from Accra in 2002.

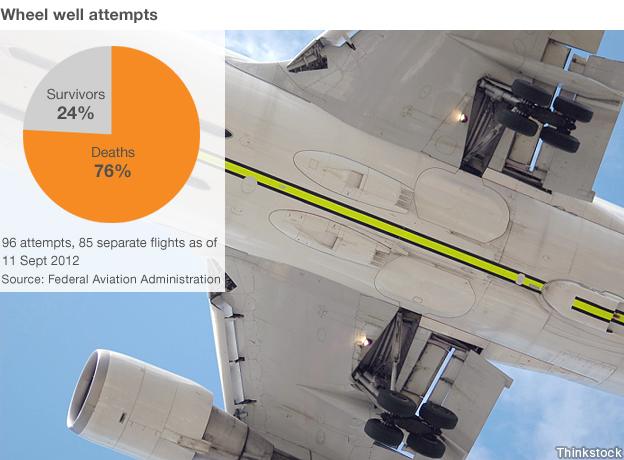

Dr Stephen Veronneau, of the US Federal Aviation Administration, has identified 96 individuals around the world who have tried to travel in plane wheel wells since 1947. The incidents happened on 85 flights. Veronneau is working on the assumption that the Mortlake fatality was a stowaway.

Of these, more than three-quarters have proved fatal.

It isn't difficult to see why. The undercarriage compartment of a plane is equipped with neither heating, oxygen nor pressure, all of which are crucial for survival as the altitude rises.

At 18,000ft (5,490m), experts say, hypoxia will set in, causing weakness, tremors, light-headedness and visual impairment. By 22,000ft (6,710m) the stowaway will struggle to maintain consciousness as their blood oxygen level drops. Above 33,000ft (10,065m) the lungs require artificial pressure to function normally.

At the same time, hypothermia is likely to be brought on, with temperatures dropping as low as -63C (-81F).

Those stowaways whose bodies are not mangled by the retracting landing gear or killed by these extreme conditions will almost certainly be unconscious by the time the compartment doors re-open a few thousand feet above ground, causing them to plunge to their deaths.

"They either get crushed or frozen to death," says aviation expert David Learmount, of Flight International magazine.

"There's a huge degree of ignorance. If anyone knew what they were letting themselves in for they wouldn't do it."

Some stowaways have survived. They tend to have travelled fairly short distances, but all rely more on luck than judgement.

In 2010 a 20-year-old Romanian survived a flight from Vienna to Heathrow stowed in the undercarriage, but only because the private jet flew below 25,000ft due to bad weather.

In 2000 Fidel Maruhi Tahiti survived the 4,000-mile journey from Tahiti to Los Angeles and, two years later, Victor Alvarez Molina made it from Cuba to Canada alive. But all suffered severe hypothermia.

With such a low survival rate, the obvious question is why anyone would embark on such a high-risk journey.

A handful of stowaways appear to have done so as a prank or out of a misguided sense of adventure. In 2010, the body of 16-year-old American Delvonte Tisdale was found on the flight path to Boston's Logan airport after he apparently hid in the wheel well of a US Airways Boeing 737 from Charlotte, North Carolina.

But such cases are exceptional. The overwhelming majority of cases involve individuals from developing countries attempting to make their way to Europe or North America.

They are also almost exclusively male - despite International Labour Organisation figures suggesting women made up 49.6% of all migrants worldwide in 2005.

Whether motivated by a desire to escape persecution or seek economic prosperity in the West, this method of transit represents the ultimate desperation.

"We don't know the circumstances of these particular people, but we know from our work with refugees that people are often forced to take extreme measures in order to flee their countries," says Deborah Harris, chief operating officer at the Refugee Council.

"In conflict situations, people often have to leave their homes at very short notice, and may have no access to money or belongings so are forced to take desperate measures to escape."

And yet it's hard to imagine even the most afflicted migrant would undertake a journey that was almost certain to lead to their death. It's easy to assume that ignorance of the sheer level of risk is what leads the stowaways to press ahead.

In the West, a public information campaign would be an obvious response to the stowaway deaths. But as the cases tend to originate from developing countries, it's hard to imagine where a concerned organisation might start.

As a result, these individuals represent a huge challenge for the authorities.

According to Norman Shanks, former head of group security at BAA, the threat to anyone other than the stowaway themselves - passengers, flight crews, people on the ground - is minimal.

But actually preventing someone slipping into the undercarriage depends on checks and procedures that are not always present, Shanks warns.

"In a lot of places around the world, the control of movement and airside control areas is not the same as what we have here."

"It's much easier in some locations to access the airside areas than it is in the UK. The only way it could be prevented is if the rest of the world tightened their procedures."

As for the man who fell to earth on Portman Avenue, police are still awaiting the results of his post-mortem.

Scotland Yard has so far been unable to identify him. But Angolan currency found with his remains offers a clue as to his origins.

A makeshift floral tribute has been left at the spot where he was found. Every few minutes, another incoming flight passes overhead.