Richard III: The people who want everyone to like the infamous king

- Published

An artistic interpretation of Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth where he was killed in 1485

King Richard III was painted by Shakespeare as an evil, hunchbacked and brutish man who plotted and murdered his way to the crown, but a society named after him is trying to restore his reputation. Why are they so upset about his portrayal?

Richard III only ruled England for two years, but it is his alleged role in the disappearance of his young nephews - the "princes in the tower" - that made him infamous.

Many historians say he remains a likely candidate for their murder, but the Richard III Society believes that Tudor propaganda is to blame for his negative image.

"We want to strip away the spin, the unfair innuendo, Tudor artistic shaping and the lazy acquiescence of later ages, and get at the truth," writes the society.

"Deformed, unfinished, sent before my time / Into this breathing world, scarce half made up / And that so lamely and unfashionable / That dogs bark at me as I halt by them"

So Shakespeare introduces his anti-hero to the stage, and the image of the king with a withered arm and crooked back has stuck.

The Richard III Society hopes the skeleton recently discovered in Leicester, possibly that of the king, will "encourage an upsurge of interest" in him.

Some people become members because they like the tale of mystery and intrigue, but the common thread, says Wendy Moorhen from the society, is a sense that Richard III has been unjustly tarnished through the ages.

"The betrayal of Richard III has gone on for 400 years. He was a man who worked hard all his life, yet he has always been portrayed as evil.

"We do not know who killed the princes but it would be out of character for Richard to murder two children in cold blood. We want to show he was a balanced, loyal man."

It is the question of whether he plotted his way to the throne, and murdered those who got in his way, that lies at the heart of the society's frustration with how he has been painted.

Despite vigorous campaigning from the society, many historians still maintain that history has not been completely rewritten.

"The Richard III Society consists of some who contain an extreme and romantic view. They publish scholarly work in the belief that it will eventually exculpate Richard III, but it hasn't actually done so," says Michael Hicks, professor of medieval history at Winchester University.

"No responsible historian would say the whole of Shakespeare's picture is wrong. His work was not just Tudor propaganda but based on the sources available at the time, some of which are still sources now."

Most agree, Hicks adds, that the king illicitly seized the throne and was ultimately responsible for the murder of his nephews.

Richard III's supporters believe anything written after his death was an attempt by the new Tudor king to butcher his reputation.

But Hicks argues that any account of him would naturally be written after the events unfolded, and that he was not important enough during his short reign for his every movement to be extensively penned.

Two influential chroniclers - Dominic Mancini and the Croyland Chronicle - written much earlier than the main Tudor sources which inspired Shakespeare's play, also paint a negative picture of him, says Hicks. Similar stories were later echoed by renowned Tudor scholar Sir Thomas More.

A number of manuscripts belonging to Richard III, which include a prayer book, a guide on how to be a good king, and literary texts in three languages have survived. These books show him as a learned, devotional and cultured medieval monarch, says historian Michael Wood.

He believes these texts are the only way of "getting behind the Tudor myth… When you look at the manuscripts you forget Shakespeare's legend of the hunchback which dominates everyone's imagination".

"He was a legitimately crowned king so the Tudors had to portray themselves as successors delivering the country from a wicked tyrant. The image of him as wicked is entirely spawned by Tudor propaganda.

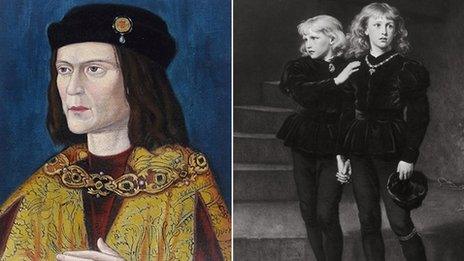

Portrait of Richard III (left) and the two missing princes (right)

"Sure he may have polished off the princes, he certainly executed some of his enemies but so did every king in the [earlier] Dark Ages."

As for his rumoured hunchback - which at the time was widely believed to be a characteristic of the devil - archaeologists say the remains found beneath the Leicester car park show signs of a curvature of the spine.

Hicks thinks this is an indication that some aspects of Tudor literature can be believed, albeit exaggerated. But Moorhen considers this as proof of Tudor slander, as such an impairment would only have given him uneven shoulders, and not a hunchback.

Though the Richard III Society hopes the discovery of what might be his remains will take them one step closer to clearing his name, Hicks suspects it will "not make a great deal of difference about what we think about Richard III".

Whatever the identity of the skeleton, the intrigue around the discovery has prompted a flurry of interest from those wishing to join the society.

Richard III: Elsewhere on the web

"Would Richard really have done away with the sons of a brother to whom he was demonstrably loyal, inviting scandal so early in his reign?" asks Ben Macintyre in The Times, external.

"Others, including Henry Tudor, had ample reason to want the princes out of the way… If the murders cannot be pinned on Richard with any certainty, then the last English monarch to die in battle has surely been maligned by gossip, political manipulation, Victorian sentimentality and literary licence."

In the Daily Mail, Simon Heffer suggests, external "there was much more to Richard than Shakespeare the pro-Tudor propagandist revealed. In fact, he had been a popular governor of his brother's northern provinces during the reign of Edward IV… Given the case against Richard III is far from proven, but there is much that we know of the good he did in a turbulent age, he deserves, with due ceremony, a decent burial."

And Allan Massie of the Daily Telegraph says, external it is incontestable that Shakespeare's Richard is the product of Tudor propaganda.

"Yet the historical Richard is a dim figure about whom even the most learned historians know very little for certain. He can't compete with the compelling vitality of Shakespeare's deformed villain.

"We don't know whether Shakespeare swallowed [Thomas] More's version of Richard uncritically, or whether he merely thought it offered irresistible dramatic material, and was unconcerned about historical accuracy. What is undeniable is that it is Shakespeare's Richard who has imprinted himself on our imagination."

- Published14 September 2012

- Published12 September 2012

- Published12 September 2012

- Published1 March 2011