History of the world: Who to leave out?

- Published

Attempting to tell the history of the whole world in one go is a leviathan of a task. Knowing what to leave out is a struggle, says Andrew Marr, presenter of History of the World.

Once, many of us got our sense of history from illustrated books or partwork series.

David Attenborough, who as controller of BBC Two commissioned Kenneth Clark's groundbreaking Civilisation, had himself been inspired by HG Wells's An Outline of History.

For me, it was other books, from Ladybirds to a massive 1920s historical encyclopaedia.

But television is brilliantly placed for join-the-dots history - it has the vividness and enthusiasm for the concrete that illustrated books share. Dramatisation can act like the coloured pictures I pored over as a boy.

But to tell each story takes between five and eight minutes so, very roughly, we knew we had up to 60 stories to choose. Where to start?

We decided to tell the story of man the social animal, and our rise from hunter-gatherers in Africa to today's clever apes and our technologically adept, seven-billion-plus domination of the planet.

Deep space and deep time, the origins of life and evolution, I left to the scientists. The same went for the hundreds of thousands of years of the emergence of Homo sapiens from earlier apes and hominids.

Quick wipe of brow. We would start a mere 70,000 years ago with the migration from Africa which spread mankind around the world. Easy.

Then, however, we decided to make it harder.

We're no longer living in the Europe-first culture where Kenneth Clark so confidently stood. This had to properly reflect a world in which China, South America and India are the rising powers.

Also, I was determined that although the vast majority of history-making figures - the names we know, the rulers, the scientists - are men, this would also pay tribute to women's contribution to history.

Clearly, human history has accelerated. The vast sweeps of time when Stone Age cultures barely changed, then the thousands of years of the farming revolution, then the towns, empires and then a frantic tumble and cascade of change.

So the early programmes cover much longer ranges of time, and as the stories move forward, the focus gets closer. But in each show, there was an agonising and mostly highly argumentative, selection going on.

It was a principle that we couldn't afford to tell the same big story twice. So, for instance, I needed to explain about absolutist rulers in the 18th Century - their ambition, their scale but also the weakness of personal rule as a way of driving a large society.

I went for the story of the Mughals in India and Aurangzeb - the 17th Century emperor who fought endless wars of expansion. It's less familiar and in some ways more important than that of Louis XIV, France's Sun King, or Frederick the Great of Prussia. They both appear in the book, but neither made the cut in the film.

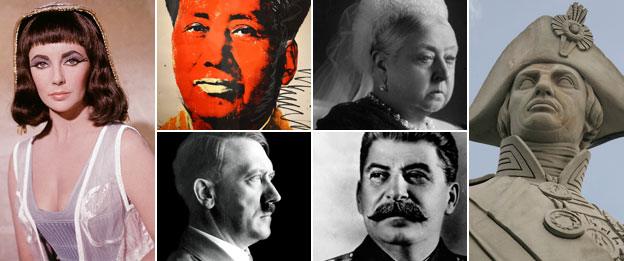

Later on, I needed to discuss the vast death toll produced by Communist dictatorship and chose Mao and Deng Xiaoping, rather than Stalin.

Then there were the practical problems. I'd wanted to show the early Mesopotamian empires but Iran and the relevant parts of Iraq were either forbidden or too difficult to film in. The same soon went for Syria, which had been an "essential" setting.

So we found ways round. The heart of the Mesopotamian story is about how the need to control rivers - for irrigation and against flooding - forced the people living around them to come together, eventually under some political authority.

That's why so many civilisations began on the banks of rivers. In Mesopotamia it produced empires, terrifying gods, the first writing and excellent maths. But something very similar happened to the Chinese clans living along the banks of the Yellow River. So we filmed there instead.

The death of Socrates - a story about open societies and dissent which reverberates loudly today - and the too little-known tale of the remarkable Asoka of India are among my high spots.

Also the super-rich empire of Mali, and the man who perhaps deserves to be the world's all-time favourite Englishman - not William Shakespeare but Edward Jenner.

Cleopatra appears as a brilliant manipulator and gutsy politician, not just a beautiful woman. Then there's Tolstoy, and the women behind the Pill, and the Viking founders of Russia.

But - rats! - I really wanted to tell so many other stories that there simply wasn't the space, time or money for. I decided people knew more British history than any other, so there is no Nelson or Wellington, no Queen Victoria, no Battle of Britain.

You know that stuff already. And as for Henry VIII, fascinating ruler though he was, in world terms he's just a fat sprat.

On this scale you can't tell the story of World War I or II, so I've taken the extraordinary tale of a Berlin civil servant, the rise of young Hitler, the massacre of Jews at Babi Yar in Ukraine and the making of the atom bomb as my representative moments.

To get in stories from Peru, Brazil, Japan, Mongolia and the Caribbean, some of the better known periods in European history slipped away. Charlemagne was galloping boldly but fell at an early fence. Charles Darwin is my all-time hero, but we've had plenty of him in recent years.

This was three years in the researching and 18 months in the filming, including the drama reconstructions made in South Africa. Writing a book, I can include far more - but there's something provocative and cheeky about the brutal selections required by television.