The rise of the Maori tribal tattoo

- Published

Moko - the art of tattoo - has always been part of the Maori world in New Zealand. It is about beauty, and belonging. And it is much more than skin deep.

When the first European explorers came into the Pacific, they were stunned by the patterning they saw on the faces and bodies of the island peoples, from Rapanui in the east, to Hawaii in the north, the westward islands of Samoa and Tonga and in the temperate south of Aotearoa - the Maori word for New Zealand.

Their languages, myths, values were similar. Tatu, or tatau, was the word used for the adornment of the skin by pricking or cutting and then applying colour. The 18th Century mariners carried the word and the tattoo itself to the northern hemisphere.

In ancient times, male facial moko was considered a mark of adulthood and achievement, as much as an active and flattering adornment. Usually the faces of men were marked from forehead to throat, creating a mask-like effect which enhanced the bone structure, softened or strengthened the features, and confirmed the virility of the warrior or the wisdom of the shaman/orator.

Ngahuia Te Awekotuku on the onomatopoeic origins of the word "tattoo"

Each line attests to the man's courage - taking moko is a painful and exacting process, and the Maori technique particularly so.

Unlike the other Pacific peoples who used comb-like instruments that tapped the ink into the skin, the Maori used scalpel-sharp chisels, which cut and scarred, gouging a raised pattern on the cheeks, forehead, eyelids, and chin.

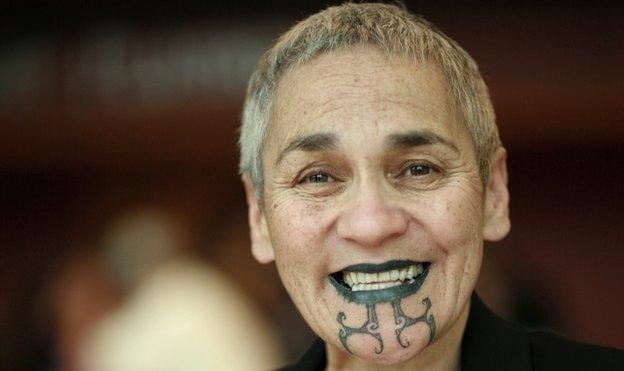

No two facial moko are ever alike. It is usually gendered - a woman's facial adornment is restricted to a panel from the central forehead (rarely done today), nostrils and below to the rich darkening of the upper and lower lips, and a design on the chin continuing into the throat.

The most common choice is the chin pattern, or kauae, which persisted throughout the colonial period, and which I saw and admired as a child growing up in the 1950s. Maori women have always had facial tattoos. Despite missionary disgust, settler vilification, rude stares and comments from strangers, they have sustained the tradition.

Why? Because it is a particular aesthetic. It defines and flatters the face, it draws attention to the eyes and lips, and a particularly skilled artist can correct flawed features and offer an illusion of beauty. And the illusion is beneath the skin, in the ink, forever.

My own skin was first marked more than 50 years ago, in a self-inflicted ritual that most Maori children observe, often with each other and usually at school with a compass point and pen, or needles bound on to a pencil and punched in.

My mark was a small arrow and, in homage to a favoured comic strip, a tiny skull that turned into a blob and was later scratched out.

Many pre-teen imprints were shallow and delible. We laugh about how it seemed to be a genetic compulsion.

Most of us moved on into parenthood and responsibility with the diminishing dots on the wrist or the cheek, the small stars or crosses on the ankle - nothing too outrageous, but the marking with ink was a shift from childhood into early adolescence, and we all did it. Parents - those who did not have actual moko - smiled indulgently and considered their own faded drawings.

Today it is more likely that young people will acquire a machine-applied design, often as a mark of excellence after gaining educational credits and degrees, or reaching a major sporting goal such as the 1st XV rugby team or a national title.

Cultural dance competitions and outrigger canoe racing are also opportunities to acquire - and to see - the best of contemporary moko. The enhanced glory of youth is on display at events such as these.

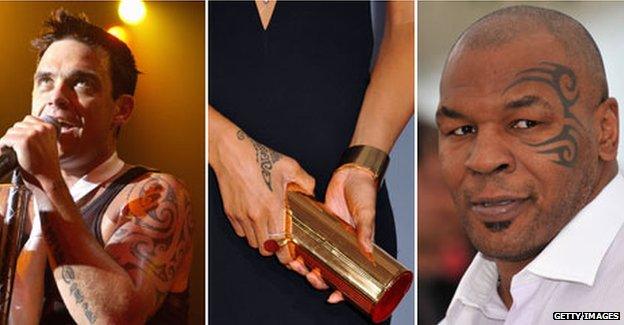

Robbie Williams, Rihanna and Mike Tyson all have tribal tattoos inspired by Maori designs

Much of this occurs on the bodies of both sexes.

Body adornment - swirling curves of black on shoulders, thighs, lower back, arms, upper feet, rear calves - has become an opportunity for storytelling as well. Some symbols represent children born, targets reached, places visited, and increasingly, memories of special people who have passed away.

In August 2006, Te Arikinui Dame te Atairangikaahu, affectionately known as the Maori Queen, died after a long illness.

Her people were devastated. Many wanted to commemorate her in a special way, and 16 women chose to memorialise her by taking a traditional facial tattoo. I was humbled to be one of them. There are now more than 50 of us, mostly older and involved in the ceremonial life of our people. It is a fitting memento mori.

But moko, most of all, is about life. It is about beauty and glamour, and its appearance on the bodies of musicians such as Robbie Williams and Ben Harper is not unusual. Although it is often contentious, raising issues of cultural appropriation, and ignorant use of traditional art as fashion.

However we must also acknowledge that Maori artists are sharing this art - they are marking the foreign bodies.

The important reality remains - it is ours. It is about beauty, and desire, about identity and belonging. It is about us, the Maori people.

As one venerable elder stated, more than a century ago, "Taia o moko, hei hoa matenga mou" (Inscribe yourself, so you have a friend in death).

Because it is forever.

The Why Factor is broadcast on BBC World Service on Fridays at 18:30 GMT. Listen to the tattoos episode via iPlayer or The Why Factor download.