Why British police don’t have guns

- Published

The deaths of two female police constables have brought into focus the unarmed status of most British police. Why does Britain hold firm against issuing guns to officers on the beat?

It's the single most obvious feature that sets the British bobby apart from their counterparts overseas.

Tourists and visitors regularly express surprise at the absence of firearms from the waists of officers patrolling the streets.

But to most inhabitants of the UK - with the notable exception of Northern Ireland - it is a normal, unremarkable state of affairs that most front-line officers do not carry guns.

Unremarkable, that is, until unarmed officers like Nicola Hughes and Fiona Bone are killed in the line of duty. There are always those who question why Britain is out of step with most of the rest of the world, with the exceptions of the Republic of Ireland, New Zealand, Norway and a handful of other nations.

For a heavily urbanised country of its population size, the situation in Great Britain is arguably unique.

Film director Michael Winner, founder of the Police Memorial Trust, and Tony Rayner, the former chairman of Essex Police Federation, have both called for officers to be routinely armed.

But despite the loss of two of his officers, Greater Manchester Chief Constable Sir Peter Fahy was quick to speak in support of the status quo.

"We are passionate that the British style of policing is routinely unarmed policing. Sadly we know from the experience in America and other countries that having armed officers certainly does not mean, sadly, that police officers do not end up getting shot."

But one thing is clear. When asked, police officers say overwhelmingly that they wish to remain unarmed.

A 2006 survey of 47,328 Police Federation members found 82% did not want officers to be routinely armed on duty, despite almost half saying their lives had been "in serious jeopardy" during the previous three years.

It is a position shared by the Police Superintendents' Association and the Association of Chief Police Officers.

The British public are not nearly so unanimous.

An ICM poll in April 2004 found 47% supported arming all police, compared with 48% against.

In 2007, the centre-right think-tank Policy Exchange found 72% of 2,156 adults wanted to see more armed police patrols.

For decades there have been incidents that have led to calls for issuing all officers with firearms. Cases like those of Sharon Beshenivsky, shot dead during a robbery in 2005, or of the three plain-clothes officers murdered by Harry Roberts in west London in 1966, or the killing of PC Sidney Miles in the Derek Bentley case of 1952.

Few expect the system to change even after widespread public horror at the deaths of PCs Bone and Hughes.

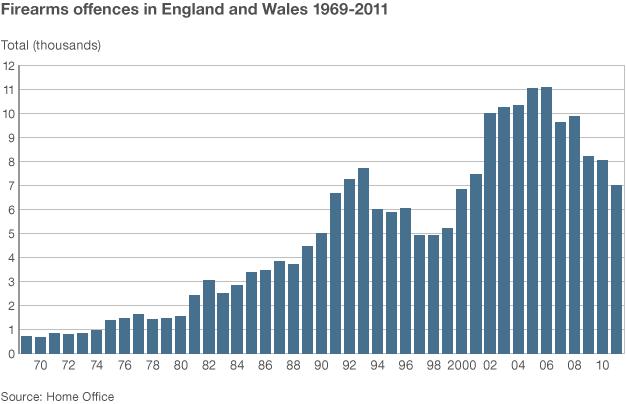

For one thing, incidents such as that in Greater Manchester are extremely rare. Overall gun crime, too, remains low.

In 2010-11, England and Wales witnessed 388 firearm offences in which there was a fatal or serious injury, 13% lower than the previous 12 months. In Scotland during the same period, there were two fatal and 109 non-fatal injuries during the same period, a decade-long low.

Additionally, officers, chief constables and politicians alike are wary of upsetting an equilibrium that has been maintained throughout Britain's 183-year policing history.

"There's a general recognition that if the police are walking around with guns it changes things," says Richard Garside, director of the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies.

Arming the force would, say opponents, undermine the principle of policing by consent - the notion that the force owes its primary duty to the public, rather than to the state, as in other countries.

This owes much to the historical foundations of British criminal justice, says Peter Waddington, professor of social policy at the University of Wolverhampton.

"A great deal of what we take as normal about policing was set out in the early 19th Century," he says.

"When Robert Peel formed the Metropolitan Police there was a very strong fear of the military - the masses feared the new force would be oppressive."

A force that did not routinely carry firearms - and wore blue rather than red, which was associated with the infantry - was part of this effort to distinguish the early "Peelers" from the Army, Waddington says.

Over time, this notion of guns being inimical to community policing - and, indeed, to the popular conception of the Dixon of Dock Green-style bobby - was reinforced.

While some in London were issued with revolvers prior to 1936, from that date only trained officers at the rank of sergeant or above were issued with guns, and even then only if they could demonstrate a good reason for requiring one.

Today only a small proportion of officers are authorised to use firearms. Latest Home Office figures show there were just 6,653 officers authorised to use firearms in England and Wales - about 5% of the total number.

None of which implies, of course, that the British police are somehow gun-free. Each police force has its own firearms unit. Police armed response vehicles have been deployed since 1991.

In addition, trained officers have had access to Tasers since 2004 despite controversy about their use. Met Commissioner Bernard Hogan-Howe called for police response officers to be routinely armed with the weapons in November 2011.

Particularly in London, the sight of armed officers at airports, embassies and other security-sensitive locations has become a familiar one, especially since the 11 September attacks.

However much firearms become an accepted part of British life, former Met deputy assistant commissioner Brian Paddick doubts police themselves will ever support a universal rollout.

For one thing, the sheer cost of equipping all personnel with weapons as well as providing regular training would be prohibitive at a time of public spending cuts, he says.

In addition, Paddick adds, front-line officers would not be keen to face the agonising, split-second decisions faced by their counterparts in specialist firearms units.

"In terms of the police being approachable, in terms of the public being the eyes and ears of the police, officers don't want to lose that," he says.

"Every case in which a police officer has shot someone brings it home to unarmed officers the sheer weight of responsibility that their colleagues face."

Cases like that of Jean Charles de Menezes, shot dead by a Met firearms officer after he was wrongly identified as a terrorist, illustrate Paddick's point.

For now, at least, that starkest of all distinctions between British officers and those abroad looks secure.

Additional reporting by Kathryn Westcott, Tom Heyden and Daniel Nasaw