Belgrade rediscovers its confidence

- Published

The word "Belgrade" conjures up images of war and "ethnic cleansing". But a new Belgrade is emerging - of music festivals and nightclubs, pedestrianised streets and designer boutiques - as Serbia prepares to rejoin the European mainstream.

The Trans-European "Express" had already broken down and had its locomotive replaced. A heatwave gripped the Balkans, but there was no water on the slow moving train and no air conditioning.

What was chilly, however, was the behaviour of the border guards, who demanded and stamped our passports - with no glimmer of a smile.

As far as Croatia, the train was packed. But after entering Serbia it slowly emptied. When we finally reached Belgrade, at nearly 3am, barely 20 passengers climbed down.

Outside, the magnificent neoclassical 19th Century station, heat-dazed stray dogs wandered dozily around. Close by stood tower blocks shattered by cruise missiles - reminders of Nato's 1999 assault on the Milosevic regime.

Belgrade has long been one of the most cosmopolitan cities in Eastern Europe, but it has a slightly faded charm. Its history has been fundamentally edgy, a gateway to the world beyond Europe.

It is a city of cafes, of chain smokers, of immigrants, many of them displaced from across the former Yugoslavia as a result of the recent wars. It still feels on the edge.

But Belgrade is also an intriguing city and one eager to rediscover the confidence of its heyday. Built around a commanding crag at the confluence of the Danube and Sava rivers, it was an important Roman settlement.

Marina Sibalic, an architect, took me up to the immense Kalimegdan Fortress, a bastion that has seen plenty of conflict - largely religious.

Indeed, the Siege of Belgrade in 1456 is remembered as a fight for the very survival of Christianity. The Christians won - then for four centuries, Belgrade swung between Muslim and Christian domination, repeatedly captured, sacked and rebuilt.

In the 19th Century it finally became the sophisticated capital of the independent Kingdom of Serbia. But today it is inevitably linked with the break-up of Yugoslavia and "ethnic cleansing".

The bitter aftertaste has not disappeared. Serbia lingers in the waiting room of EU membership. In fact, Serbian public support for joining Europe has fallen to just 50%.

I met a former official of the old regime - I will call him Dr X. Improbably dressed like a CIA man in an American-tailored pale blue summer suit, he spoke angrily of the West's "betrayal" of the Serbs.

He insisted that Serbia might never join the EU, and, his eyes glittering with malice, he predicted the collapse of the entire European enterprise.

Naturally, younger Serbians want to shrug off the legacy of that generation.

We had walked in baking heat along the elegant Prince Mihailo street, now pedestrianised and packed like the centre of any modern capital with designer boutiques.

We were heading to the famous Hotel Moskva for afternoon tea. Serbian cakes are orgiastic creamy concoctions, emblematic of the city's past - with names like Alexander Cake, Moscow Cake, and Reform Tart.

As we tucked in, Marina's daughter Iva, who has studied in England, told me younger Serbians see themselves as citizens of the world.

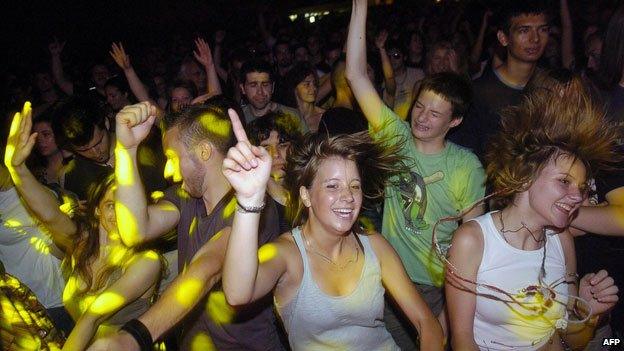

She was planning a night on the town and that is one way the Serbian young are reclaiming their city, for Belgrade has, improbably, become one of Europe's clubbing capitals.

Serbia is now home to two internationally renowned music festivals and Belgrade has a vast number of nightclubs, many of them located on scores of barges that line the riverbanks.

Those converging rivers really are at the heart of Belgrade. And I will not easily forget a lazy day we spent on the river Sava.

We had driven through Belgrade's steadily expanding suburbs, to our friends' little shoreside weekend house.

We motored to an uninhabited, forested island where small boats were moored on a sandy beach. Butterflies fluttered about and crates of beer lay all around, as Serbian families splashed in the warm, chocolate-coloured water.

Later, we ate fried sturgeon on a restaurant barge, with a bottle of wine from a vineyard called Radovanovitch.

Propped beside the bar was the neck of an enormous amphora, perfectly preserved and almost certainly Roman. It had been recently pulled from the muddy riverbank, the waiter told me. A manifest symbol of Belgrade's very ancient history.

A proud history that is worth preserving - especially, perhaps, if it helps eclipse uneasy memories of the more recent past.

And a few miles east in central Belgrade the Sava is spanned by a magnificent new bridge, the kind of landmark statement modern cities like to make, a declaration of Belgrade's determination to re-enter the European mainstream.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent:

BBC Radio 4: A 30-minute programme on Saturdays, 11:30 BST.

Second 30-minute programme on Thursdays, 11:00 BST (some weeks only).

Listen online or download the podcast

BBC World Service:

Hear daily 10-minute editions Monday to Friday, repeated through the day, also available to listen online.

Read more or explore the archive, external at the programme website, external.