Sao Paulo: A city with 180km traffic jams

- Published

Next time you complain about being stuck in traffic, spare a thought for the drivers in Brazil's biggest city, which has some of the worst congestion problems in the world.

Friday evenings are a commuter's worst nightmare in Sao Paulo.

That's when all the tailbacks in and out of the city extend for a total of 180km (112 miles), on average, according to local traffic engineers, and as long as 295km (183 miles) on a really bad day.

Red brake lights stretch as far back as the eye can see, blinking repeatedly as drivers endure an exasperating stop-and-go journey, which can continue for hours.

"It's like a sea. A sea of cars," says Fabiana Crespo, as she slowly navigates the congested streets with her 10-month-old baby Rodrigo.

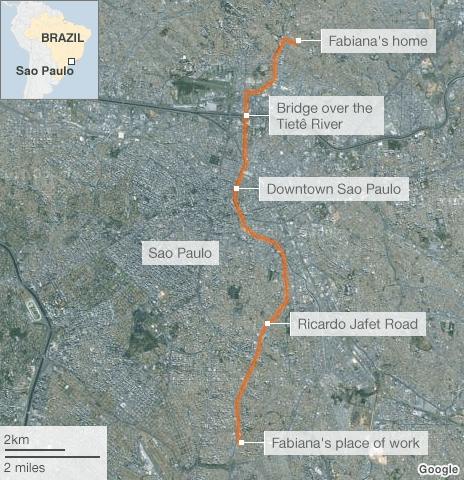

"For a long time I lived with my family in the south of Sao Paulo and worked on the other side of town.

"So when I got married, I decided to move to the north of the city to be close to the office, because commuting can make your life hell," she says.

"But after my first son was born I decided to go back to running the family business which is in my old neighbourhood. So I am back to the ordeal crossing the whole city to go to work."

Commuter Fabiana Crespo shows Paulo Cabral what her daily commute is like

For Crespo it's a journey that can take more than two hours of her day - each way.

Traffic jams cause problems all over the world, and not just for drivers, but in Sao Paulo they have become more than a nuisance.

Heavy traffic is an integral part of life and culture in this vast city of more than 11 million people.

"We have become slaves of traffic and we have to plan our lives around it," says Crespo.

By the time she gets back home after another stressful two-hour commute it is already evening, and her husband is waiting with their older child, three-year-old Pedro.

However she also knows that it is a certain irony that it was in one of those terrible congestions nine years ago that she met the man she would eventually marry.

"I was with a friend in my car and he was in his car also with a friend. In the stop and go of the traffic jam we started driving side by side and then he started looking at me," says Crespo.

After some flirting through the car windows, Mauricio managed to convince Fabiana to give him her phone number. He called, and an enduring love story began.

"I think this is the only thing we can't complain about in Sao Paulo's traffic," she says.

However for most motorists, the story is one of frustration and local news radios dedicate considerable energy and airtime to ensure motorists are fully up to date.

There is even one station dedicated exclusively to reporting traffic conditions and alternative routes, 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Since it was set up seven years ago, Sul America Traffic Radio has gathered a large following of listeners who also act as reporters, calling in to update other motorists or to vent their frustrations.

During rush hour, the station has the support of a helicopter while a team of reporters is out on the road, often stuck in traffic themselves.

Among them is Victoria Ribeiro, whose job is to drive around town finding traffic jams - not in itself much of a challenge - and to find ways to escape the mess.

"I have been working with the radio since its beginnings and we can see the traffic is only getting worse, as more cars are coming onto the streets," she says.

Sao Paulo radio station to help gridlocked commuters

The Brazilian car industry has been breaking successive production records over the last decade, as the income of millions of Brazilians has improved thanks to economic growth.

Owning a car is a widely held aspiration, offering an alternative to the city's deficient public transport system, and the ultimate proof of belonging to the middle class.

However while the explosion in car sales was essential to sustain Brazilian economic growth, it has also pushed Sao Paulo's "sea of cars" to a whole new level.

"It's like a war, because everybody seems to become very selfish once they are behind the wheel of a car," says Ribeiro.

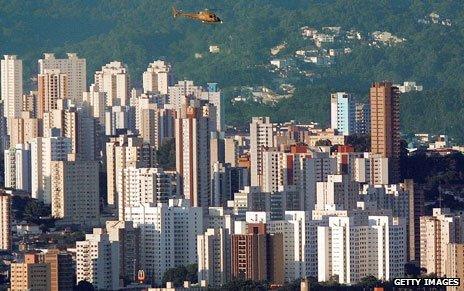

For those who have enough money there is another option - they can literally hover above the problem.

The combination of bad traffic and fear of crime - two major concerns in Sao Paulo - a growing helicopter industry is able to ferry around the super rich or business executives.

"If I hire a helicopter for a few hours I can hop between helipads and have three or four meetings in one day, which would be impossible if I had to move back and forth by car," says legal consultant Sergio Alcibiades, who uses an air taxi service a few times a month. "For me this is a tool to make money."

The owner of Helimart Air Taxi, Jorge Bittar, says his company is enjoying an average growth of 10% a year and has 16 helicopters that rarely stay on the ground for long.

"When it comes to traffic, the worse it gets, the better it is for us."

There may be opportunities for some but traffic jams also have a negative impact on the economy.

The Marginal Pinheiros is a key Sao Paulo highway

The heavy traffic has a huge impact on the cost of living and doing business, says Claudio Barbieri, a professor in engineering and transport expert from the University of Sao Paulo.

"If you have a truck and this truck cannot make more than six to eight deliveries instead of 15 or 20, you need two trucks, so everything becomes more expensive."

Prof Barbieri says Sao Paulo has skilled and experienced traffic engineers that somehow manage to get the city to flow, albeit slowly.

"But the big problem is that we Brazilians are terrible with planning and traffic will only become more manageable if we start looking into real long-term solutions."

But he is also clear that a "more manageable traffic" environment is the best possible scenario that can be achieved.

"No city in the world will ever manage to end congestion because when traffic flows, people are drawn to their cars. The key is to find a balance, the point at which it is worthwhile for commuters to use public transport because it's faster then driving," he says.

"That way Sao Paulo needs urgently to invest more in public transport instead of building new roads and expressways that will only be filled up with more cars."