How China became the US election bogeyman

- Published

American fears about China's economic strength have fed into the US presidential election campaign - shaping public fears in some surprising ways, according to new research.

Foreign rivals have long been used as foils in US elections.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, Japan played the role of bogeyman. Tokyo's rising trade surplus with Washington came to symbolise fears of declining American competitiveness. And US presidential candidates vied with each other over who could be tougher on the Japanese.

In the 2012 American election, China has become the test of presidential resolve. Both President Barack Obama and his Republican challenger Mitt Romney have pledged to ratchet up the pressure on Beijing.

Romney has promised that on his first day in office he will issue an executive order branding China a currency manipulator, possibly triggering a trade war. And on 17 September, the Obama administration filed an unfair trade case at the World Trade Organization against alleged Chinese subsidies of auto parts exports.

There are substantive reasons for this. China accounts for 40% of the record US merchandise trade deficit. But the political rationale for such actions and promises is also clear.

Trade action allows a candidate to stand up to foreigners (who don't vote), while demonstrating concern about the economy and its victims, a political triple play. Most important, recent public opinion surveys show that such rhetoric and initiatives have broad support, especially among Republicans.

Most Americans describe relations between the US and China as good and most consider China a competitor rather than an enemy or partner, according to a new survey by the Pew Research Center, external.

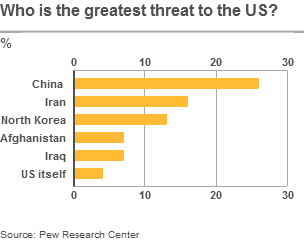

At the same time, when asked which country represents the greatest danger to the US, more Americans volunteer China (26%) than name any other country, including Iran and North Korea. And about half (52%) view China's emergence as a world power as a major threat to the US.

Republicans are more concerned than Democrats about the impact of China's rise. Six in 10 Republicans believe Beijing's rise as a world power poses a major threat to the US, compared with 48% of Democrats. And Republicans (74%) are more likely than Democrats (61%) to say China cannot be trusted.

Moreover, contrary to the popular narrative that Democrats are protectionists and Republicans are free traders, far more Republicans than Democrats see the US trade deficit with China as a very serious problem for the United States.

Similarly, GOP members are more likely than Democrats to worry about the loss of US jobs to China. And Republicans are more concerned than Democrats about the large amount of American debt held by the Asian nation.

With such concerns, it is hardly surprising that Republicans are also far more likely to favour toughness with China on economic and trade issues. Democrats are more likely to say building a strong relationship with China is a top priority.

About two-thirds of Republicans say it is very important for Washington to be tough with Beijing, compared with 53% of Democrats. At the same time, 59% of Democrats believe building a strong bilateral relationship with China should be a top priority, while only 48% of Republicans agree.

And GOP voters also think they can do a better job than the Obama administration in dealing with China. Republicans are nearly twice as likely as Democrats to say the president should be tougher on Beijing.

Security issues involving China are less of a public concern or a partisan issue. Only about half the public is worried about cyber attacks from China or Beijing's growing military power and just 27% are concerned about tensions between China and Taiwan.

And there is no real difference between the party faithful on Beijing's military ambitions nor its relations with Taipei.

The 6 November US presidential election will not be determined by the candidates' stance on China.

But given the public's fairly hawkish views on China, both Obama and Romney will not shy away from continuing to sound tough on Beijing. Whether the victor will carry through on his promises will not be known until next year.