Who What Why: How durable is a fingerprint?

- Published

The three main fingerprint types - the loop, the whorl and the arch

American Hans Galassi lost several fingers in a wakeboarding accident several months ago. Now one of them has been found in a trout - and identified as Galassi's from its fingerprints. So how long do fingerprints last?

The vast majority of people are born with a unique set of fingerprints which remain the same for life.

These patterns, known as friction ridges by experts, are found not only on our finger-tips but also on the flanges of our fingers, on our palms, our toes and on the soles of our feet.

The patterns are permanent, but can wear down. Builders who lay bricks and people who frequently wash dishes by hand lose some of the detail. Once they stop these activities, the ridges will grow back.

As fans of crime movies will know, from time to time people have tried to change their fingerprints patterns artificially.

A deep cut through the outer layer of the skin, the epidermis, and down to the dermis leaves a scar that will change a fingerprint, but not make it any less unique.

People have also sought to erase their fingerprints by burning the finger-tips with fire and acid, as the notorious 1930s American gangster John Dillinger did. It works for a while but the skin grows back.

Another criminal, Robert Phillips, famously grafted skin from his chest on to his fingers to erase his fingerprints - but he was identified from the prints of his palms. Others have tried smoothing their finger-tips with glue and nail varnish. Again they were caught from palm prints.

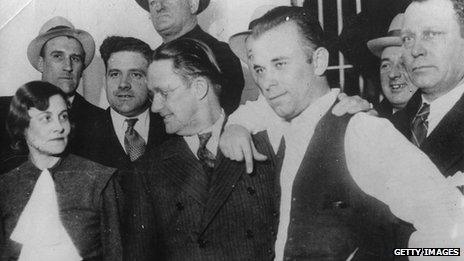

John Dillinger (in waistcoat) tried to burn off his fingerprints

Friction ridges are remarkably long lasting even after death, says fingerprint expert Allen Bayle, author of the UK's standard police manual on dead hands.

"If a hand is found in water you will see that the epidermis starts to come away from the dermis like a glove. This sounds gruesome but if a hand has been badly damaged, I cut the epidermis off and put my own hand inside that glove and try to fingerprint it like that," says Bayle.

"Some boys we get out of the water, the fish have been at them already and the fish will have pecked at the epidermis. But you can still get ridge detail from the underside of the epidermis. And if that has gone, then you can do the dermis. For every ridge you have on the epidermis, you have two on the dermis - we call it a tramline effect."

The speed at which a hand disintegrates in water depends on many things, not least the temperature of the water itself.

"If the water is very cold, it could stay for a long time," says Bayle. And the body of a trout, the fish that swallowed Galassi's finger, is just as cold as the water it swims in.

Galassi's finger was found in the trout's digestive tract - why hadn't it been digested? We shall never know how long after the accident the fish ate the finger, but Bayle thinks even if the thick layer of epidermis had been digested, Galassi's finger could still have been identified from its dermis.

"We can cast [the finger], for example in latex, and then we can ink the cast. Or we can ink the dermis and roll it on a fingerprint form. When we have got some ridge detail then we can put it on the computer."

In the case of Galassi, Idaho police took a day searching case files and reports to narrow down where the finger could have come from. They then fingerprinted the stray digit and sent it to the state police forensic lab where technicians were able to identify its owner.

"One of the last things to disappear when you die are your fingerprints," says Bayle. "They're very durable."

Hans Galassi spoke to Newshour on the BBC World Service

- Published27 September 2012