Crimea's Tatars: A fragile revival

- Published

After persecution during Soviet times, Crimean Tatars have returned to their homeland in Ukraine where they are trying to rebuild their lives.

Rustem Eminov, now in his mid-40s, was sent into exile when he was just three-months-old.

His family was forced to leave the Crimea and was resettled in far-away Central Asia.

It was not until the breakup of the Soviet Union, when he was in his 20s, that Eminov was finally able to live in the land of his birth.

Over cups of green tea in a room shaded against the fierce sun, he tells me his story.

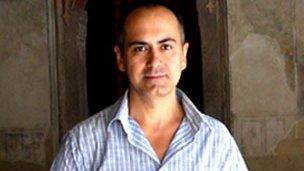

Like many Crimean Tatars, Eminov grew up in exile

Now a specialist in the history of the Crimean Tatars, Eminov is the director of ethnography at the Historical and Culture Reserve in the old Crimean town of Bakhchisaray.

A handsome clean-shaven man, with a smile on his face and an open manner, my wife and I meet him in his little office across the moat from the palace of the old Khan - the Crimea's last Muslim ruler. It's one of the few remaining monuments to the history of Crimean Tatar people.

Despite his exile, Eminov acknowledges that he is one of the lucky ones. Many Tatars suffered much worse treatment.

In 1944, Stalin decided to send the entire Tatar population of the Crimea into exile.

The excuse for the collective punishment of old men, women, and children was that they had collaborated with the occupying German forces during the Second World War. Around 200,000 people were pushed on to trains and sent - for the most part - to Uzbekistan.

It was disastrous - almost half the population died within a year. They were forced to live in what Eminov ironically calls "reservations".

It was not till the 1960s, that the Soviet government softened its stance towards them - the charge of collaboration was dropped, and in 1967 the Crimean Tatars were pardoned.

But they still were not allowed to go home. It wasn't until 1987, when Russian President Mikhail Gorbachev introduced his reforms, that the Tatars were finally allowed to return to Crimea.

But in the previous 40 years their homeland had changed. Their houses were now lived in by others, mainly Russians and Ukrainians, who had no wish to give them up.

To make things worse, few Tatars had been able to bring back much in the way of wealth from Uzbekistan.

"Just imagine what 200,000 people trying to move at the same time does to the price of flats," says Eminov. Families had to start from scratch.

I heard one such story from a man called Ruslan, who did not want to use his surname. Born in Uzbekistan, he was 10 when his family managed to move back to Crimea.

Ruslan worked as a shepherd in a kolkhoz, a collective farm, on the north Crimean steppe. When the Soviet Union split up the collective farm simply collapsed.

Without much education or many marketable skills - there isn't much call for sheep-shearing these days in Ukraine - Ruslan moved down to the coast and now works as a driver.

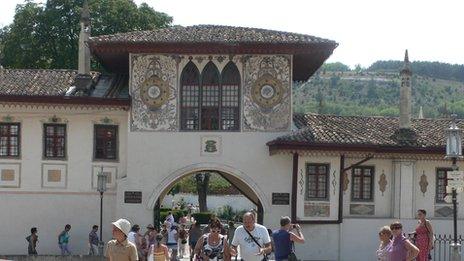

The Khan's palace in Bakhchisaray is the only major building complex to survive from the Crimean Khanate

Crimean Tatars are starting small businesses but reviving their culture is a much harder task. One of the great difficulties is just how little of it has survived.

The Crimea has always been a contested land. The peninsula has been fought over for centuries.

Russian armies twice devastated Bakhchisaray. All that now survives are a few private houses and mosques - crumbling away in the town's backstreets - and the magnificent palace of the Khans.

In the 1820s, some 40 years after the end of the Crimean Khanate, the Russian writer Alexander Pushkin visited the palace and wrote a poem about the unhappy love of a Crimean Khan for his Polish concubine.

The white marble fountain he described in The Fountain of Bakhchisaray is still there, dropping a single tear-like droplet of water, again and again.

The association with Russia's national poet seems to have helped preserve this sad little fountain - rather ugly black bust of Pushkin now stands next to it - and indeed helped to save the entire exquisite complex of halls, courtyards and gardens.

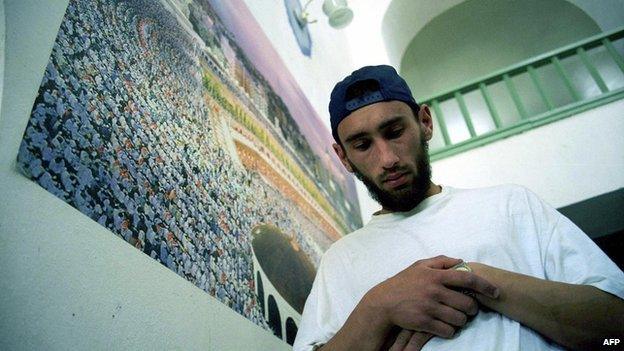

Old mosques in the town's back streets have been reopened to worshippers

The Crimean Tatar revival is real but it is still fragile. Eminov talks of the religious pressures and is concerned that, despite Ukraine's secular constitution, in practice the state favours Christianity, and even builds churches.

An Islamic revival is under way, but will it be the Islam of old Crimea or of modern Arabia?

Many Crimean Tatars fled to the Ottoman Empire in the 19th Century and the Turkish government is currently paying for a new madrassa - or Koranic school - and what is described as an "archaeological reconstruction" - which sounds rather like a contradiction in terms.

There is a great risk of an artificial version of the Crimean past.

However, as I sit on the terrace of a Bakhchisaray restaurant enjoying its hearty Central Asian dishes of lagmam and shorpa - noodles and stew - my worries about an ersatz future drift away.

The Tartars are home. They are clearly survivors.