Readers' own adventurous expeditions

- Published

The Magazine's recent article about the world's remaining adventures prompted readers to respond with examples of their own feats.

It questioned whether any ground-breaking explorations remained undone. Here, eight readers describe their own expeditions.

Visiting every country in the world without flying

Graham Hughes, of Liverpool, has nearly visited every UN-recognised country in the world - including some unrecognised territories - travelling only on land and by sea.

I've already been to 198 countries (190 members of the UN) and have just three more to go before I complete my journey. It's taken me three years and nine months to get this far, with no professional support and living off a shoestring budget and relying on the kindness of strangers.

It's cost me everything I own - and my 10-year relationship - and there have been plenty of trials and tribulations along the way. I got arrested twice in Guinea, God-knows how many times in Cameroon and spent a week behind bars in both Cape Verde (on a charge of people smuggling) and Congo (on a charge of being a spy). But, to be fair, that was a small and inconvenient part of what has been a wonderful, hilarious, incredible adventure.

Iran was the country that least lived up to preconceptions, becoming the highlight of my trip. I was warmly welcomed into people's homes, invited for dinner, helped along the way - it was incredible.

I'm now in Sri Lanka, trying to arrange passage on a cargo ship to the Maldives and the Seychelles (islands + piracy = immense difficulty in getting there without flying).

I hope to hit my final country, South Sudan (the newest country on Earth) in November and then overland it back to Blighty for tea and biscuits by December.

This adventure has reaffirmed my faith in humanity. OK, I've run into some trouble with authorities, but most people - in every town of every country - are just trying to get on with their lives and will fall over themselves to help a stranger in need.

Seven seas, seven summits

Graham Hoyland, of Derbyshire, aims to be the first person to climb the highest mountain on every continent and sail the "seven seas" - the five oceans, with the Pacific and Atlantic in separate north and south trips.

Through my work as a film-maker I'd already climbed Mt Everest and Mt McKinley in Alaska, as well as sailed the Southern Ocean to Antarctica, when it struck me as an opportunity to do something no one else has ever done.

When I was made redundant in 2009 I decided to make the attempt full-time. So I bought a cheap sunken sailing boat, rusting from the inside out, and have since sailed the North Atlantic. In a way it's a race against rust.

I've just skied up (and down) Mt Elbrus in Russia and am sailing to South America this week to climb Mt Aconcagua.

I've been scraping together enough money in any way that I can, but the flight to climb Mt Vinson in Antarctica is too expensive - about £30,000 - so I'm going to sail the Southern Ocean, the Everest of oceans, for a second time.

The sea scares me more than mountains. It can really feel like it's out to get you and sometimes you feel very vulnerable.

I'm hoping to complete everything within three or four years.

Flying around the world in a gyrocopter

Norman Surplus, of Larne in Northern Ireland, is attempting to be the first person to circumnavigate the globe on a gyrocopter, or autogyro - an early forerunner to the helicopter.

The gyrocopter is the last remaining method of flight yet to be flown around the world, despite its near 90-year history. I only began flying in 2005 after battling bowel cancer, which I am now fundraising for during this attempt.

I left Northern Ireland in March 2010 and have flown through 18 consecutive countries so far. One adventurous moment was an emergency landing next to a remote Saudi Arabian petrol station during a desert sandstorm - luckily the gyro's preferred fuel of choice happens to be regular unleaded.

I'm now in Japan, where I've been effectively grounded since July 2011 due to Russian red tape. The most frustrating aspect is that the Russians simply do not provide any feedback on my application to cross their airspace. Unfortunately Russia acts as the "gatekeeper" for crossing the Bering Sea to Alaska and this remains the only viable route for small aircraft crossing the Pacific Ocean.

I remain optimistic that the flight will be allowed to continue in spring 2013. I'm then aiming to set a new coast-to-coast record across the US before taking on the challenges of Greenland and the North Atlantic to return home.

Caving in northern Spain

Ben Hudson, of Oxford, this year led a caving expedition to Pozu del Xitu, northern Spain, where two divers completed the world's deepest cave diving traverse - entering one cave and exiting another - at a vertical distance of 1265m and 9km horizontally.

What I find so exciting about caving is that it is an entirely unexplored wilderness with enormous potential for discovery. But it's also easily accessible for anyone who is trained and fit. I only started caving two years ago and this year I led a world-class expedition to Pozu del Xitu in northern Spain - that's pretty exciting. And it hasn't cost me an enormous amount either.

Over four weeks, we rigged the cave with modern hardware down to a depth of 1,135m. Underground trips typically lasted three or four days, with an underground camp at a depth of about 650m. The final rigging trip - from camp to the bottom and back again - took three of us more than 25 hours of non-stop caving.

Tony Seddon and Paul Mackrill then completed the world's deepest cave diving traverse between the Culiembro and Xitu caves, before ascending the ropes we'd put in place throughout the cave.

Mountain climbing in Iraq

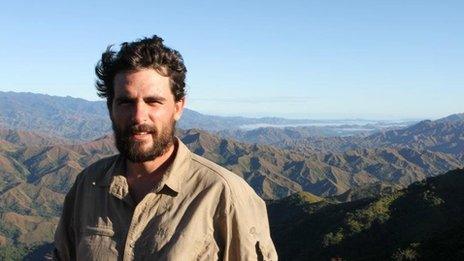

Levison Wood, of London, runs a company specialising in "world firsts", leading him up numerous unclimbed peaks.

After leaving the Army two years ago, I became a full-time expedition guide and explorer. Many remaining world firsts are in countries that have a troubled history, which leads us to post-conflict zones such as South Sudan, Sierra Leone, Afghanistan and Iraq.

A local mountain guide with AK-47

Earlier this year I led a team of six to Kurdistan, where we went up not only unclimbed but even unnamed mountains. Close to the Iranian border, with occasional Turkish bombing raids, the region still has its dangers. We were actually arrested by local militia and held overnight - although they were very helpful once they realised we were there to promote tourism in the area.

One of our crew skied down the mountain over minefields that would have been uncrossable had they not been buried by 2m of snow.

But it's not just former war zones that contain firsts. I recently led the first expedition across Madagascar from east to west and have plans for many more.

Rowing the Northwest Passage

Kevin Vallely, of Vancouver, Canada, plans to row the Northwest Passage - once sought by explorers as a possible trade route to the Orient - in a single season.

Our crew of four will be the first to row the Northwest Passage, the historic gateway to the Orient. We will start from Tuktoyaktuk, northern Canada, on 1 July 2013 and row east for 24 hours a day whenever possible. We'll be rowing in two-man shifts, in perpetual sunlight. We're hoping to complete it in about 75 days but we're grasping at straws when talking time on an expedition like this - there are just too many variables. But there is a cut-off date. If we don't finish by October we'll have serious issues with freeze-up.

There is a wider issue than just being the first. Not long ago the Northwest Passage was inaccessible even by steel-hulled ice-breakers. If we can succeed at traversing it using only human power, it will scream to the fact that dramatic environmental changes are underway. Maybe our trip will help this reality bubble to the public consciousness just a little bit more.

If we succeed, it will be a human first, but we have no illusions about what this means. It will be a human first because the world has changed. This will be very sobering.

Exploring the West Papuan jungle

Will Millard, of Downham Market in Norfolk, has been exploring the Indonesian conflict state of West Papua for the past five years.

West Papua is one of this planet's last unknown frontiers. Since 2007 I've made friends with local warriors and explored the region, becoming aware of the "Great Road" - a vast inter-tribal trade route and one of the longest running foot-only routes in human history - yet almost unnoticed by the outside world.

This year I set out to make the first unbroken, unassisted crossing of the province (more than 1,000km), linking the Great Road to the coasts through new trade routes. In some stretches of forest, my colleague and I were almost certainly the first humans, let alone outsiders, to have been there.

Ultimately we didn't make a full crossing of the province. Our proposed route was not a trade route at all, and we were left beating a nearly disastrous jungle retreat, losing two stone each and almost running out of food.

In May I returned solo and discovered a different route to the coast to finish the project.

I've barely scratched the surface of this under-researched province's potential, but fear it may disappear before it is ever fully understood. Who knows what is out there still yet to be discovered?

Abseil UK's highest waterfall, then kayak gorge below

Richard Bannister, of Harrogate in Yorkshire, plans to abseil down the Falls of Glomach in Scotland, before kayaking down the gorge below.

I'm 35 and a married dentist and father of one, but I still make time for the odd adventure.

I've been white water kayaking for about 12 years and I'm a competent kayaker but am not out to be the best. What appeals to me most is running new or little-known rivers and exploring them. Finding these places in the UK is rare and makes it all the more special.

This brings me to my plans for November.

The Falls of Glomach in Scotland are the highest permanent (never dries up) waterfall in the UK at 114m. Almost certainly no one has ever been down this gorge at all, as it is practically inaccessible, and there's no evidence of any previous attempt. It's so deep and shear-sided, you cannot see the majority of what lies below.

Depending on water levels, after abseiling down the waterfall we'll either canyon (that is, walk, swim and climb) or kayak down from there. There is a definite air of the unknown, so we'd need to call upon our skills and experience from various disciplines to get down. But what a trip.