The slow spread of Vegemite

- Published

Vegemite started as a wartime substitute for Marmite, but it's now as symbolic of Australia as Sydney Harbour Bridge and the koala. How did this salty spread become so popular?

What's the link between German U-boats, the beer industry, processed cheese and the Men At Work's 1983 hit, Down Under?

The answer is, they all played a part in turning Vegemite from a humble yeast spread into an Australian icon. Stop any Aussie on any street, anywhere in the world, and they will have a view on Vegemite - for, or against.

Now, on the eve of its 90th birthday, the first official history has just been published. The Man Who Invented Vegemite is written by Jamie Callister, grandson of the man who created it.

"My grandfather Cyril created something that all Australians associate with their childhood. It never leaves you," he says.

Vegemite's inventor Cyril Callister

The story really begins in the late 19th Century, when an edible by-product was first extracted from the yeast used by brewers to make beer. In 1902, Britain's Marmite Extract Food Company came into being, taking its name from the French word "marmite", for large pot.

Marmite was sent around the world, including to Australia. But during World War I, those exports were badly interrupted by German U-boats attacking merchant ships.

"Supplies of Marmite all but dried up, leaving Australians desperate for the spread that many had come to love," says Callister. "They needed to find an alternative."

That's where Cyril Callister comes in.

Born in 1893 in rural Victoria, he was a clever child who went to college and became a chemist. He lived an exciting, unorthodox, life, travelling the world and ending up as a scientist at a munitions factory in Scotland.

After an explosion at the factory, Callister returned to Australia, where he met an entrepreneur called Fred Walker, who was trying to develop a Marmite substitute.

Walker had already seen one local brewer try to come up with its own version of Marmite, called Cubex. But this thick, bitter sludge was a culinary and financial disaster.

Walker put Callister on the case in 1923, and by the end of the year, the pair were confident they had a finished product. Walker decided to launch a competition so the public could name it and claim a £50 prize. Hundreds entered and it was Walker's daughter Sheila who pulled the word Vegemite out of a hat.

Like the product itself, the name stuck. But sales were sluggish.

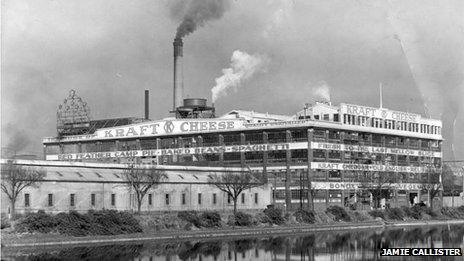

Walker had heard about an ingenious Canadian called James Kraft, who had perfected what came to be known as processed cheese. It was a sensation, as it allowed people who couldn't afford fridges to store cheese for much longer periods.

In 1924, Walker met Kraft in Chicago. The two men got on well and Walker persuaded Kraft to grant him rights to sell his cheeses in Australia.

In a stroke of marketing genius, he offered Vegemite alongside the cheese. By the mid 1930s, Vegemite was, if not quite a runaway success, certainly a moderately well-established family staple. But it took a professor of human physiology to transform its fortunes.

Kraft's involvement marked the beginning for Vegemite's success

Cedric Stanton Hicks worked at the University of Adelaide and he was commissioned by the Australian government to ensure troops marched on full stomachs.

After extensive research, Hicks concluded that Vegemite, a rich source of vitamin B, should become the basis of soldiers' ration packs along with blackcurrant concentrate and margarine.

"Hicks sent Vegemite to war and that transformed its status," says Jamie Callister.

As World War II unfolded, Vegemite became associated with the national interest. Posters put up in Australia had pictures of it with the slogan, "Vegemite: Keeping fighting men fighting fit."

For Vegemite, the war was a turning point, marking its entry deep into the hearts and consciousness of the Australian public.

In 1949, Cyril Callister died. A sign of his and Vegemite's importance came when Robert Menzies, a past and future prime minister, turned up to his funeral.

By the 1950s, advertising executives sealed the product's place in Australian minds with their radio jingle, Happy little Vegemites, a tune so catchy many adults can still hum it with nostalgic ease.

And if that were not enough, in 1982, a reference to Vegemite appeared in Men At Work's worldwide hit, Down Under, external.

No Aussie forgets the words of what many consider to be Australia's unofficial national anthem: "I said 'Do you speak-a my language?' He just smiled and gave me a Vegemite sandwich."

But it hasn't all gone Vegemite's way.

In 2011, on a visit to Washington, the Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard discussed Vegemite with President Obama, who concluded it was "horrible".

And some nutritionists have long been concerned by its relatively high salt content, even though Vegemite has experimented with lower sodium varieties.

Vegemite is certainly not unique. It still has a British counterpart in Marmite and you can buy German, Swiss and New Zealand versions of yeast-extract spreads.

But for Australians, it is special. Each year, 22m jars are sold, one for every man, woman and child in Australia.

And while most Aussies would struggle to name the man who created it, Cyril Callister's legacy continues to define Australia, with Vegemite remaining an essential ingredient in the cultural glue that binds Australians.