Doctors and nurses forced to pick cotton

- Published

After some international clothing firms such as H&M, Adidas and Marks and Spencer boycotted cotton from Uzbekistan in protest at the use of child labour, this year most Uzbek children are able to get on with their schoolwork. But office workers, nurses and even surgeons are being forced into the fields instead.

Malvina, a nurse at a clinic in Tashkent, is angry.

"I am almost 50 years old and I've got asthma. We had to pick a lot of cotton, all by hand - and we were not paid anything!"

She has just returned from a 15-day stint picking cotton with other health professionals in rural Uzbekistan. It was hard toil and no-one was spared, whatever their seniority.

"Some people phoned our surgeon, who was with us in the fields.

"They would say things like: 'You operated on me a week ago. I've got a temperature - what shall I do?'"

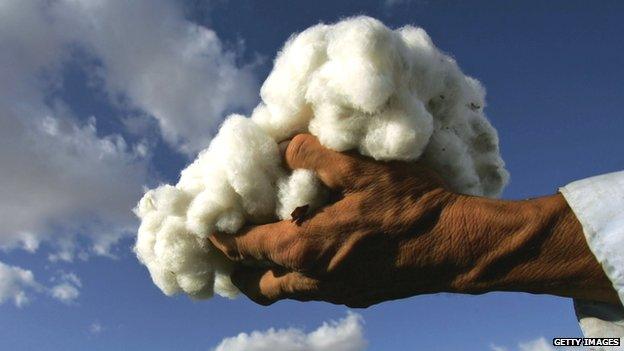

Uzbekistan is one of the world's main producers of cotton and the crop is a mainstay of its economy. The government controls production and enforces Soviet-style quotas to get the harvest off the fields as quickly as possible.

A history of using child and forced labour at harvest time has led to a number of retailers - including H&M, Marks and Spencer and Tesco - to pledge to source their cotton from elsewhere.

In response, earlier this year Uzbekistan's Prime Minister Shavkat Mirziyayev issued a decree banning children from working in the cotton fields. Yet many adults, including teachers, cleaners and office workers, are still forced to return to the land during October and November.

This year, like last year, medical staff have been ordered to join them. There are reports of patients in towns being turned away because their doctor is "in cotton".

The BBC is not allowed to report from Uzbekistan, but Malvina - not her real name - told us that since last year, Tashkent's authorities have required every district to contribute 330 medical staff.

There followed a bad-tempered meeting at her clinic to decide who would do the work. Unfortunately for Malvina, it became clear that having asthma wasn't enough to get out of the chore.

"It seemed that everybody had something - back pain or high blood pressure or whatever. And when the head doctor heard this list of illnesses she said: 'Stop it! I don't want to hear any more. Everybody is going apart from pregnant women and those nursing babies.'"

Anyone who refused to go would be dismissed, she said.

Malvina says that the workers were woken up at 04:00 in the morning and had to walk for more than an hour before starting work. They finished around 18:00 in the evening.

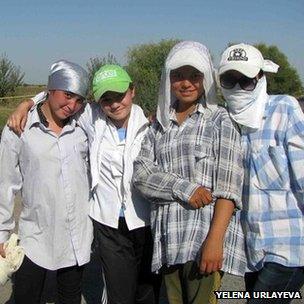

These young cotton-pickers were photographed this year

"We had to pick 60kg of cotton each. If we didn't hit that target, then we had to buy the rest from locals," she says.

Malvina and her colleagues from the clinic were supposed to be put up in a school, but there wasn't enough space. In the end they rented their own accommodation. To wash they had to pay another fee to use a local bathhouse.

For many Uzbeks, the cotton season presents an unpredictable burden. A college lecturer from Samarqand region, who did not wish to reveal his name, told us he was too ill to pick cotton this year.

"I had to find a labourer and pay him $100 to pick cotton for me," he says. "Then the college principal withheld my monthly salary, saying it was going to be used to feed and house the labourers - so I lost another $200."

But he is happy that schoolchildren are being spared this year and can carry on with their education.

The decree banning child labour does appear to have had some effect. Yelena Urlayeva, an activist who travels across the country every year to document abuses, has noted a few incidents where children have been drafted in to make up a shortfall.

The Uzbek authorities have so far refused to discuss cotton-picking with the BBC, but a website close to the government recently denied the presence of any children among this year's cotton-pickers.

Under the terms of the decree, a "child" is anyone under the school-leaving age of 15. Students over this age are still bussed out to help with the harvest, and all colleges and universities have closed their doors as usual. For Urlayeva, these pickers are also too young.

"They are still children, and some of them get sick because the conditions are so harsh. It gets very cold and the food is just not good enough." She says that parents who try to remove sick children from the harvest are threatened with their expulsion from college.

One of the organisers of the boycott, the pressure group Responsible Sourcing Network, says the Uzbek government has not yet done enough.

"What we were asking for in order to lift the boycott was for the Uzbek government to invite an ILO [International Labour Organization] mission, to monitor the situation in the field," says Cotton Programme Manager Valentina Gurney. "Despite our insistence, this has not happened."

Forced labour is found in a number of countries around the world, but it is only in Uzbekistan that it is orchestrated by the government, Gurney says.

According to the International Cotton Advisory Committee, Uzbekistan accounts for about 4% of world cotton production, and 10% of world cotton exports. At the same time cotton accounts for about 45% of Uzbekistan's total exports.

For decades "white gold" has been important culturally too.

Uzbeks are encouraged from a young age to look forward to the time of year known simply as "pahta" - cotton. The harvest is an opportunity for them to contribute to their nation's prosperity.

For Malvina, there is the certainty of further cotton-picking "opportunities" in the future. Her workplace has signed an agreement with the farm for the next five years.

Malvina spoke to Outlook on the BBC World Service. Listen back to the interview via iPlayer or browse the Outlook podcast archive.

- Published20 September 2011