How do sexual abusers cover their tracks?

- Published

As allegations mount against Sir Jimmy Savile, more and more people are asking how he was able to act with apparent impunity. How do predators escape detection?

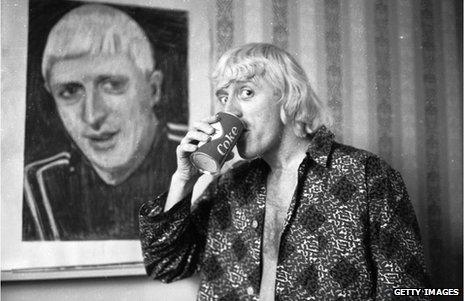

Jimmy Savile has been described as an expert at "hiding in plain sight". He was the eccentric who seemingly joked openly about his sex life, the knight who surrounded himself with children and spent part of his life living in hospitals.

But despite this, Savile's alleged sexual abuses went uninvestigated in his lifetime.

Scotland Yard says it is following up 340 lines of inquiry following complaints of abuse and sexual assault by Savile.

And yet Savile was hardly a furtive figure, hiding in the shadows.

His 1974 autobiography boasts of having taken home an "attractive" runaway from a remand home before he handed her to the police. As columnist Hugo Rifkind observed in The Times:, external "It was right out there, in plain view, and nobody wanted to see."

In a 2000 BBC interview with Louis Theroux, Savile said he told journalists he didn't like children to put newspapers "off the hunt".

Equally, a persona forged on a love of children can be a common disguise for a sexual predator.

Journalist Malcolm Gladwell wrote in the New Yorker, external how former football coach Jerry Sandusky concealed years of grooming and sexual abuse behind his "loveable goofball" personality and a life that was "all about the kids".

According to David Wilson, professor of criminology at Birmingham City University and a former prison governor, the allegations against Savile "match the classic profile of a predatory paedophile operating within institutional structures that support their fantasy life".

Not only do such offenders tend to be adept at hiding their crimes, they will often use their social status to deter complaints against them.

"Sexual abusers can hide behind their position," says Christiane Sanderson, a counsellor and expert on child sexual abuse.

"If someone is in a position of authority, or if they have become a pillar of the community, it is very difficult for victims to come forward. They will be afraid of repercussions and the reprisals in terms of whether they will be believed."

Sanderson draws on comparisons with the Catholic Church and the cover-up of sexual abuse in Ireland.

"There is a record to say that people did try to come forward and try to actually make some allegations and they were not believed because it was so difficult to believe that somebody with such status, power and authority would abuse this power and sexually abuse," she says.

While academics are keen to stress that there is no stereotype for a sex offender, there are common techniques employed by abusers to cover their tracks.

It is often the case that they will draw on their power and position, the fear that their victims have, and the shame and guilt that victims feel.

Just as Savile reportedly did, many abusers tell their victims that they will not be believed if they ever tell anyone what has happened to them.

"Abusers use a combination of fear and threats, they cover their tracks by telling the victim that it's their fault," says Sarah Nelson, a specialist researcher in childhood sexual abuse, from the University of Edinburgh.

"Everyone who has spoken about the Jimmy Savile case talks of feeling ashamed. Abusers are often very clever at making their victims feel complicit, that it was partly their fault."

Nelson adds that the careful choice and grooming of the victims is another way in which abusers can attempt to conceal their behaviour.

Victims are often vulnerable, handpicked by someone who has a sense of power over them.

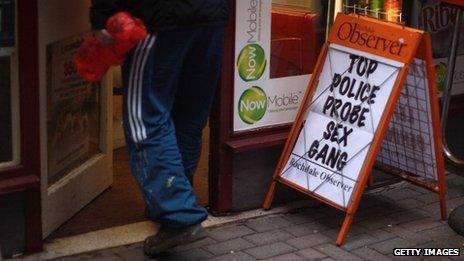

The scale of the abuse in the Rochdale sex ring, and the subsequent review of the work of the local agencies who were tasked with safeguarding the children, has highlighted this.

Nine men were jailed in May for grooming girls as young as 13, but in many cases the victims, often from troubled backgrounds, were initially assumed to be "engaging in consensual sexual activity" or even involved in prostitution.

"The grooming took place in public for years," says Nelson.

"They went to cafes and restaurants. They were giving them presents, drinks, acting like their boyfriends before these girls were passed on to be abused, but they chose stigmatised girls, girls who were already in trouble or considered delinquent.

"They were categories of victims that the public didn't care much about."

If such exploitation is to be prevented, experts agree that victims and potential victims must be given a voice.

"We have a culture which used to want children to be seen and not heard," says Wilson, who once ran the sex offenders unit at HMP Grendon and has conducted extensive research into both victims and perpetrators.

"Lately we've been more tolerant of children speaking but we don't always listen to them."

Correctly, he says, inquiries into Savile will focus on why so many institutions enabled and ignored his alleged behaviour.

"But for me, the key issue is that we allow children the space to speak - and that we listen to what they tell us," Wilson says.