Philippine politics - it's a family affair

- Published

Politicians in the Philippines have been filing their candidacies for next year's elections - and there are some familiar names. Very familiar. In fact, it's hard to avoid the impression that politics here is a form of family business.

Imelda Marcos and Joseph Estrada are two of the best-known names in the Philippines.

Both have been ousted from the presidential palace - Mrs Marcos as the wife of President Ferdinand Marcos, and Mr Estrada when he himself was president.

Both have also faced lengthy trials for corruption.

But neither is a quitter. Imelda is already a congresswoman, and at 83-years-old she's putting herself forward for another three-year stint. She's not the only Marcos back in government - her son is a senator and her daughter a provincial governor.

At 75, Joseph Estrada is hoping to become Manila's mayor. His son is running for the Senate - to join a half-brother who's already there.

Brothers, wives, uncles, children - Philippine politics is dominated by certain families. And evidently, even if one of them is very publicly deposed, they're not out of power for very long.

"It may be the 21st Century, but in reality this is still a very feudal society," says political analyst Marites Vitug.

It's not just families from the past who keep appearing on the ballot, either - new dynasties are forming too. The famous Philippine boxer Manny Pacquiao won a Congress seat three years ago, and now his wife and brother are running for positions alongside him.

Of course political dynasties are not confined to the Philippines. India has its Nehrus and Gandhis, Pakistan its Bhuttos, even the US has had the Kennedys and the Bushes.

But the trend is particularly evident here, despite what Filipinos insist is a vibrant democracy.

Part of the problem is that Filipinos need a lot of money to campaign for votes - and wealth is concentrated among certain families.

Manny Villar is one of the few senators who's not from a well-known name - in fact he says was born in a squatter camp and once sold shrimps in a market.

But by the time he ran for political office, he'd already made his millions in business - and he says that private money is essential to any election campaign.

Yet even he believes money isn't as good as family connections - the reason he gives for his failed presidential bid in 2010.

"You can go far, but I don't think you can be president without being from one of those families," he says.

Bam Aquino, a cousin of President Benigno Aquino, acknowledges that his relatives are a great help in his current run for the Senate. At just 35, it's difficult to see how else he could have a chance of winning.

But he insists there are other ways of getting known too - fame, even infamy, can be a substitute for family ties.

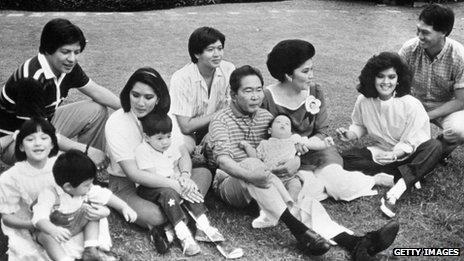

The Marcos family in 1986

Many movie stars and talk show hosts seem to find their way into politics - and, as two current senators have discovered, launching a failed coup also seems to launch a political career.

Bam Aquino acknowledges that the system isn't ideal, but says he doesn't see why that means he shouldn't run.

"I was six years old when my uncle [the current president's father, Ninoy Aquino] was shot. It changed my life. I saw Filipinos coming together, wanting democracy. Because of that I've always wanted to be in politics."

"If people like me are willing to serve, we shouldn't just stay by the sidelines. All good people need to engage. Why should we wait?'

He raises an interesting point. How much damage is actually done if politics is in the hands of a few big families, as long as they run the country well?

According to Marites Vitug, a great deal of damage. "It seriously limits the growth of other people who aren't as rich," she says.

"And it stifles politics. These people have vested interests - to perpetuate things the way they are, for themselves."

"I can accept it if a doctor has a family business, and passes it on his son, but being in the Senate should not be a family business."

If this is the situation nationally, it's even worse in local politics, where one family often has a complete monopoly on power - passing posts around their relatives so they effectively rule the whole area.

In an extreme example of the damage this can cause, members of the Ampatuan clan - the most powerful family in Maguindanao province - are alleged to have killed 57 people in 2009, purely because of their anger at a rival who dared to challenge their stranglehold on power.

So can this system ever change? According to Senator Villar, the key is to bring people out of poverty, and provide better education.

"When we develop economically, the influence of these family dynasties will go down significantly."

Bam Aquino thinks that political parties first need to be more mature and stable - at the moment candidates frequently flit from one party to another. Then they will be able to nominate candidates "whatever their last names are", he says.

Marites Vitug agrees with both of these suggestions - adding that there should also be a law to limit the number of politicians from each family.

There's clearly a growing public appetite for change. A local newspaper columnist, Solita Monsod, recently suggested that Filipinos "pledge not to vote for anyone whose surname is the same as, and/or who is related to, an incumbent public official".

And when Interior Secretary Jess Robredo died in a plane crash a few months ago, there was widespread public mourning for a politician seen as one of the exceptions - a man who rose up the ranks not because of fame, fortune or family, but because he was good at his job.

But the Philippine public isn't entirely consistent in the campaign against political dynasties.

In response to intense public demand, Jesse Robredo's widow has just announced that she's running for office.