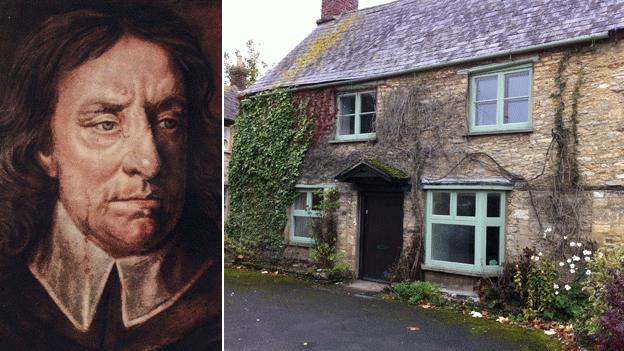

Oliver Cromwell: Is my house's name controversial?

- Published

If you inherit a house named after a controversial figure from history, should you consider renaming it?

Cromwell House has unobtrusively graced the Oxfordshire village of Bampton since about 1600.

By the time my much-loved aunt Margaret moved there during World War II, the cottage had carried its name for almost 300 years.

The story goes that during the English Civil War Oliver Cromwell beat a small detachment of Royalist troops, at a skirmish known to a few specialist historians as "Bampton-in-the-Bush".

On that night in April 1645, he slept in rooms above the blacksmith's forge.

My aunt spent all her adult life in the property, and when she died, she left it to me, and my four sisters.

Now I am buying it outright, but it presents me with a real moral dilemma. For some, particularly in Ireland, Oliver Cromwell is a war criminal, an ethnic cleanser. He has even been accused of genocide.

I have spent 10 years covering wars where ethnic cleansing and the terrorising of civilian populations have happened on a huge scale.

In Iraq and elsewhere I have seen firsthand the misery inflicted by people who use killing and intimidation to try to achieve political goals, and I have been traumatised by what I have witnessed.

Seeing blood running in the street and hearing the screams of the dying and bereaved are memories that will stay with me forever.

Many of the people responsible for those cruel acts believed that they were enacting God's will - a motivation Cromwell shared.

Irish historian Micheal O Siochru wrote what has been described as "the definitive account" of Cromwell's war in Ireland. The book's title is God's Executioner.

"I think it would be a good idea to change the name," he told me.

"Hold up a picture of Cromwell and everyone in Ireland knows him - they might not know the exact details, but they know this man was responsible for some terrible crimes."

Cromwell's acts included the massacre of the garrisons - and hundreds of civilians - at Drogheda and Wexford in 1649.

In the four years following Cromwell's departure from Ireland, while he was still commander-in-chief, one fifth of Ireland's population died as a result of violence, starvation or disease.

And tens of thousands of civilians were transported to the Americas as "indentured servants" - virtual slaves.

"This was total war, a systematic destruction of infrastructure, agriculture and people, and this was an act of deliberate policy", O Siochru says.

"This was ethnic and religious hatred. Cromwell's legacy was to set England and Ireland on a path of bitterness and violence for three hundred years".

Thousands were massacred in Cromwell's 1649 siege of Drogheda, Ireland

My Irish friends all have a very similar reaction - horror.

"Cromwell's name is spoken and spat on here," one told me from Dublin, adding - in a failed attempt to soften the blow - "in a metaphorical sense".

Another suggested that it would be like living in a house named after Radovan Karadzic, the Bosnian Serb leader currently being tried for war crimes in the Hague.

But there is another side to Cromwell.

He defeated Charles I in the English Civil War, and in the process established parliamentary pre-eminence over the monarchy.

Cromwell put that king on trial, establishing that a monarch is not above the law. He eventually earned himself a statue outside the Houses of Parliament.

His request to a portrait painter to depict him "warts and all" has taken on proverbial status.

From just up the road from Bampton, the Oxford historian Sarah Mortimer tells me her students at Christ Church "often admire Cromwell".

"He was a charismatic leader who played a key role in building English military greatness, and liberty of conscience for Protestants."

She feels the tag of war criminal is undeserved, and Cromwell's conduct in Ireland should not be judged through modern eyes.

"What happened in Ireland was in line with contemporary laws of war. By the standards of the time, if you hold out against a besieging army and refuse their terms of surrender, you deserve what you get when you are finally defeated."

She also doubts that Cromwell was motivated by religious or ethnic hatred, feeling that he actually pitied Ireland's Catholic people, believing they were deluded and misled by their priests.

"Cromwell wasn't any more anti-Irish than many of his contemporaries. But his speeches were so long and rambling that even at the time people struggled to understand what his motives really were."

Cromwell refused to become King of England, ruling as Lord Protector

And so far as the English Civil War is concerned, my own view is quite clear. Given a choice between parliament - however imperfect - and a king who believed he had a divine right to rule, I know which side I would have been on.

So, will I change the name?

The more I think about it, the less I believe I have the right to.

It is likely that the house took on the name organically rather than as a conscious decision by a previous owner. It was the Cromwell house, the house in the village that Cromwell stayed in, and so its name is a description, not an endorsement.

Ownership of the house is a temporary state - like Cromwell, I am just passing through.

In the end, Cromwell House has been a part of Bampton's long history for three and a half centuries.

And history should be history - warts and all.

- Published29 July 2011