Cuba missile crisis: When nuclear war seemed inevitable

- Published

Fifty years ago, the world teetered on the brink of nuclear war, after the USSR deployed nuclear missiles in Cuba. Many ordinary people feared the worst, and so, it appears, did those closely involved - both in the East and the West.

In October 1962, CIA official Dino Brugioni wrote a farewell letter to his wife and instructed her to open it only if he told her to do so.

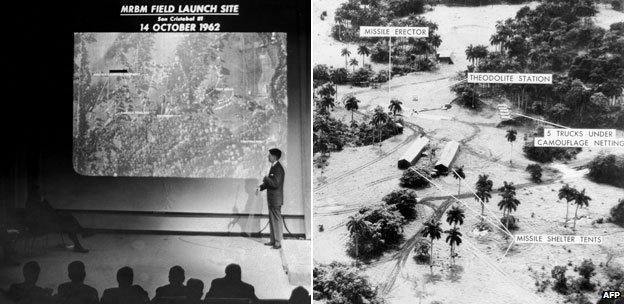

He was well placed to know just how serious the situation was. Based in the National Photographic Interpretation Centre, his job was to prepare briefings for President John F Kennedy on surveillance pictures of Cuba.

"Those photographs meant a crisis," he recalls.

They offered incontrovertible evidence that the US's Cold War enemy, the Soviet Union, was equipping its ally, Cuba, with nuclear missiles capable of striking Washington and other US cities.

America's nuclear bomber force was scrambled, and detailed plans laid for an invasion of Cuba.

The US government advised using sand-filled bricks for fallout shelters

Brugioni made arrangements for his young family to get out of Washington in the event of war.

"When I got afraid was Black Saturday, 27 October," Brugioni recalls. "We got word to get ready to go to the underground."

The "underground" was a bunker where the president could go in an emergency, to carry out his duties. Brugioni was expected to accompany him.

"I called my wife that night and told her, 'If I call you again, put the kids in the car and set out for Missouri,' - where my parents live - because I was convinced we were going to be bombing the missile sites on Monday.

"I had an eight-year-old daughter and a one-year-old son. Just the thought of my wife packing them up and leaving hit me pretty hard.

"But I had seen atomic blasts and I knew the destruction they had left, and I felt sure that Washington would be a target."

When the US Secretary of Defence Robert McNamara went home that night he too "wondered if there'd be another dawn", remembers Brugioni.

A Gallup poll showed one in five Americans thought a third world war was about to break out.

US radio stations were playing adverts with tips on how to survive a nuclear Holocaust.

"That was the most frightening time the United States has been through," says Gen William Y Smith, who spent the crisis in the Pentagon as special assistant to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

He advised his brother to build a fallout shelter in the basement of their childhood home in Arkansas. But he saw no point in trying to save his own life in Washington.

"I didn't think any of us were going to survive. It didn't make a lot of sense to do any planning because it wasn't going to work."

On the other side of the world Sergei Khrushchev, the son of the Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, was coming to the same conclusion.

"I knew all the destructive forces of nuclear weapons because I worked with them," he says - he was an engineer involved in the design of cruise missiles.

"There was a feeling that if there is war, then it will be inevitable death for everybody and there is no place where you can hide."

Convinced an attack on nuclear-armed Cuba was just hours away, Nikita Khrushchev spent the night of the 26th at the Kremlin - a rare occurrence, his son says.

"He thought it would really be the beginning of the end of the world," recalls Sergei.

"He decided to be there because if Americans will really invade this night, better to be in the Kremlin than at home."

It was unknown for Sergei's father to sleep at his office in the Kremlin

For many years, Soviet citizens had lived within range of American Thor and Jupiter missiles stationed in Turkey, Italy and Britain. But this was the first time Americans had been directly threatened by Soviet nuclear missiles. Cuba is just 90 miles from Florida.

Europeans also had reason to be afraid. The eastern half of the German capital was already in the Soviet orbit. It was thought the crisis might embolden the USSR to snatch West Berlin from Allied control.

In Cuba, the armed forces were on their highest alert. William Rakip, aged 17 at the time, was in the youth militia and was assigned to escort a convoy carrying weapons parts to the western province of Pinar del Rio.

"I sat in the sidecar of an old motor bike with a machine gun on my lap," he recalls.

"We were worried about what was going to happen but we weren't afraid about losing our lives. We hadn't a real notion of what a nuclear war could be. Hiroshima, Nagasaki sound for Cubans like fairy tales. We never had a real consciousness of what it meant."

Nikita Khrushchev did. He had seen enough bloodshed in World War II to be terrified of war.

"My father could not even watch movies about the war because he could not sleep afterwards," remembers his son, Sergei.

Late on 26 October, he wrote an emotional letter to his US counterpart, President Kennedy, imploring him "not now to pull on the ends of the rope in which you have tied the knot of war".

Kennedy, equally keen to avoid what he called "the final failure", responded in kind, and the world was brought back from the brink.

Just in time. Pentagon staffer Smith believes nuclear war was a matter of hours away.

"It came close, I tell you," adds Brugioni. "The countries had claimed we were going to go to the brink, and basically once we got to the brink, we didn't know what the hell to do."

Fortunately, his wife never did have to read his farewell letter, and Brugioni kept its contents a secret.

Jo Fidgen's report on the Cuban missile crisis was broadcast on the BBC World Service's Witness programme. You can download a podcast of the programme or browse the archive.