Ikea at 25: How has flatpack giant changed the UK?

- Published

It's 25 years since Ikea landed in the UK, with a store in Warrington. How has it changed British life?

We're on first name terms with Billy, Malm and Hemnes. They come in birch veneer, black-brown, oak veneer and white.

There's also Odda, Lack, Konsmo and Fjellse but Britons don't know them as well.

Since Ikea opened its first UK store in Warrington a quarter of a century ago, the Swedish business's product lines have become a fixture in the nation's homes. Brits have bought eight million Billy bookcases. One in five people sleep on an Ikea mattress, and it's even been suggested that one in 10 babies are conceived in Ikea beds.

It now has 19 stores in the UK. So what has been the Ikea effect?

Matching homes

It can be disconcerting to walk into a friend's house and be given a glass of water in the same style of tumbler as you've got at home.

Then you sit on the same sofa and put the glass on the same coffee table.

You glance up at the same poster of a meadow and take a book from the same Billy bookcase - probably if this scenario is to be kept alive - one of Stieg Larsson's Millennium trilogy.

Many homes, while well put together, are instantly recognisable from the Ikea catalogue.

Around the world, a Billy bookcase is sold every 10 seconds. The designer Wayne Hemingway is a fan. All the storage units are from Ikea in his house, as is the kitchen.

But Kirstie Allsopp, property consultant and TV presenter, abhors the uniformity. "I find that idea of everyone having the same stuff really scary. We aren't all the same."

Rite of passage

Stop for a moment as you test out that swivel chair and survey the Ikea panorama.

It is almost the Seven Ages of Man speech from Shakespeare's As You Like It.

There are the 20-something couples about to move in together, holding hands and gazing into each other's eyes as they stretch out on the double beds. Expectant parents study the baby products with grim intensity. A divorcee contemplates life without so much as a kettle or teaspoon to their name. Large groups of students wander around with candles, wineglasses, rugs and pictures.

It has become a cliche - when your circumstances change in life, people drift to Ikea. And buy a cushion.

Out-of-town stores

The Design Museum's Michael Czerwinski talks about how Ikea has changed furniture design, at a special historical display of the company's products

Ikea's huge blue and yellow sheds in out-of-town retail parks are a familiar sight.

Other shops follow and a new retail zone is born, albeit one dependent on the car.

Ikea has struggled with out-of-town retail planning laws in the UK, says Johan Stenebo, author of The Truth About Ikea, and a former aide of the company founder Ingvar Kamprad. If it had its way it would have gone beyond its current total of 14 stores in England, two in Scotland and one each in Wales and Northern Ireland.

Swedish design

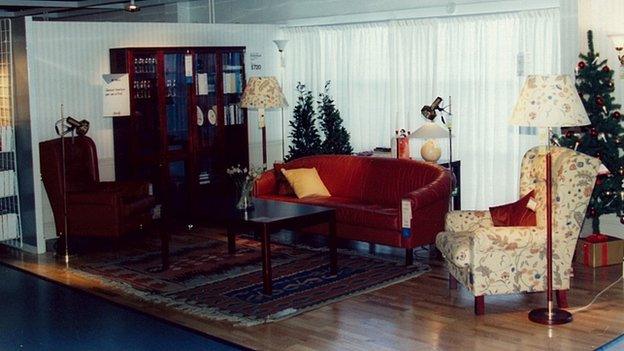

A furniture display inside the Warrington store in 1987

Ikea is a place of smooth, unfussy lines.

The range is huge. It's logically displayed and so Scandinavian - light and airy with a scent of birch forest. Ikea is a force for good, says designer Wayne Hemingway. "They care about design and it's very adaptable and customisable."

Despite the fact Hemingway's house is full of Ikea products, you wouldn't recognise them, he says. "Every bit of our kitchen looks amazingly bespoke but it's all Ikea with different things added. We even customise their bathroom cabinets."

But Allsopp loathes the look. All too often, people move into houses and throw out good quality furniture in favour of new Ikea stuff, shipped over from China.

"I love nice Swedish design but that's not what it is. It's chipboard rubbish." And the beds are different sizes to everyone else's so you end up being forced to buy all the sheets and pillow cases there.

"It drives me nuts," she says.

Getting lost

Negotiating your way through the store has made for many a pub rant.

At first it's like the open road. The possibilities are endless as you stroll from room to room, eyeing up the different products.

You will sleep better, start having friends over for dinner, and tackle the clutter. Then at a certain point of traipsing - 45 minutes in my case - a red mist descends.

You become wracked by doubt and a crushing sense of defeat. Perhaps the Malm is a better option. Or what about Anebode? Will the bedside table fit the space? Suddenly you don't care. You simply have to get out. But there's no quick way out, external.

You seem to be like a lab mouse, stuck in a psychologist's maze. You usually emerge clutching something, whether it's a toilet brush or an extension lead. Stenebo says the walking route is carefully designed.

"Every 10 or 15 yards there's a small curve that causes the eyes to divert from the horizon to the products. There are bins throughout the store full of toilet brushes or tea lights. It's spoonfeeding."

Meatballs

In the cafes there are budget meatballs, almond cake and weak coffee.

The Swedish flavours have developed a strange sort of following, despite the school dinner vibe of the packed cafeteria.

The company says it has served 11.6 billion meatballs and 1.2 billion hotdogs in the UK.

Stenebo says the restaurant side of the business has always been close to the heart of Kamprad.

"He thought that hungry people are not good customers." For that reason the cafe is always between the showroom and the market place.

Flatpacking

Ikea brought self assembly to the masses. You observe the products in the showroom, note down the model number and collect them in flatpack form from the warehouse-like market place.

Then you try and assemble it.

"This is like some... game where you climb through wood and screws on your hands and knees… and if you don't hurt yourself, you get a shelf," as one blogger put it, external.

Flatpack is much derided but allows costs to be cut massively on transport, says Hemingway. "We can all have a laugh about how much we hate it, but it's the best way."

Next comes assembly and following those wordless instructions featuring the Michelin-style man. And contrary to reputation the instructions are uncannily accurate. If it doesn't fit together, it's invariably because of human error. The next problem is getting rid of the mountain of cardboard.

Cheaper furniture

The Swedish firm continues a trend for democratising good design that Habitat started in the 1960s. But some of its prices are rock bottom.

Lamps, duvets, blankets, cushions, glasses can be bought for a few quid. They resemble loss leaders but are not, Stenebo insists.

"Ikea is the world champion in offering value," he says. It's the main reason for their success, Hemingway agrees. Where else can you buy a double bed, mattress and sheets for under £200?

Allsopp disagrees. Customer service is better at John Lewis and environmental standards superior at B&Q. Often people are better off buying second-hand. "We need value, customer service, sustainability and originality," she says. But some might find it hard to argue with a £4 duvet.

Crowds

The public hunger for Ikea can cause problems. At its most extreme, it resulted in a brawl, external at the opening of the Edmonton branch in 2007. People were trampled, scuffles broke out and someone was stabbed - allegedly for trying to bag a sofa reduced to £45.

The slowness to get into online shopping exacerbates the overcrowding, says Stenebo. It still doesn't offer its full range on the website. The restrictions on opening new stores in the UK make them the most overcrowded Ikea outlets in Europe, he says.

"The UK stores are not a nice day out. There are so many people. At the Wembley store it was close to impossible for us to offer a good visit. It was always overcrowded so they couldn't offer the whole range."

All-pervasive brand

Like pickled herring or Dancing Queen, Ikea divides people into tribes of love , externaland hate, external. But it goes further. For some Ikea is more than a very successful furniture store. It's a hopeful, Scandinavian lifestyle that we can all own. The satirical site the Onion ran a spoof piece, external on Ikea "claiming another 10,000 lifestyles".

The firm is moving into hotels, external and designing a neighbourhood of East London. The byproducts of Ikea - from the stubby pencils, free tape measures and bright blue bags - have leeched into the nooks and crannies of the nation's homes. A couple got married at Ikea in Maryland, external this year, complete with portions of meatballs. It has a cultish quality, some argue, external.

They're selling a fake vision of Scandinavia with a load of "sodding unpronounceable names", Allsopp argues. Stenebo accepts that much of the Swedishness is a gimmick laid on with a trowel. The design team is based in Sweden but they scour the globe for ideas.

The flipside of the argument is that it's not a cult but a business giving people something no-one else offers. The closest UK business one can think of to Ikea - Argos - is shutting dozens of stores. "Name another Ikea and you can't," Hemingway says. That means they're either getting everything wrong or nobody thinks they can do it better. "And I think I know the answer to that."