Have India’s poor become human guinea pigs?

- Published

Narayan Survaiya's mother Tizuja Bai died several weeks after being given new drugs

Drug companies are facing mounting pressure to investigate reports that new medicines are being tested on some of the poorest people in India without their knowledge.

"We were surprised," Nitu Sodey recalls about taking her mother-in-law Chandrakala Bai to Maharaja Yeshwantrao Hospital in Indore in May 2009.

"We are low-caste people and normally when we go to the hospital we are given a five-rupee voucher, but the doctor said he would give us a foreign drug costing 125,000 rupees (£1,400)."

The pair had gone to the hospital, located in the biggest city in Madhya Pradesh, an impoverished province in central India, because Mrs Bai was experiencing chest pains.

Their status as Dalits - the bottom of the Hindu caste system, once known as untouchables - meant that they were both accustomed to going to the back of the queue when they arrived and waiting many hours before seeing a doctor.

But this time it was different and they were seen immediately.

"The doctor took the five-rupee voucher given to BLPs [Below the Poverty Line] like us and said the rest would be paid for by a special government fund for poor people," Mrs Sodey explains. "This was really expensive treatment for the likes of us."

What Mrs Sodey says she did not know was that her mother-in-law was being enrolled in a drugs trial for the drug Tonapofylline, which was being tested by Biogen Idec. Neither could read and Mrs Sodey says she does not remember signing a consent form.

Mrs Bai suffered heart abnormalities after being given the trial drug. She was taken off it and discharged after a few days. Less than a month later, she suffered a cardiac arrest and died at the age of 45.

The trial, which was registered in the UK by Biogen Idec, was later halted due, say the company, to the number of seizures recorded. The company also says Mrs Bai's death was not reported to them.

Her case is not an isolated incident.

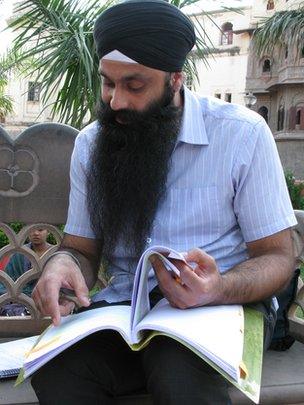

In a different trial with a different company, Narayan Survaiya says neither he nor his late mother Tizuja Bai were asked if she wanted to participate, or even told that she was taking part in one, when she sought treatment for problems with her legs. And, like Mrs Sodey, he claims the family were told that a charity was footing the bill for the care.

A few weeks after taking the drug, Mr Survaiya says his mother's health deteriorated and she was left unable to walk.

"I told the doctor, but he said don't stop the doses. It is a temporary paralysis and the drug will make it better."

His mother died a few weeks later.

In all, 53 people were test subjects in that trial, which was sponsored by British and German drug companies, and eight died. There is no hard evidence that the drug was the cause of death, but nor were there any autopsies to enable a full investigation.

Over the past seven years, some 73 clinical trials on 3,300 patients - 1,833 of whom were children - have taken place at Indore's Maharaja Yeshwantrao Hospital. Dozens of patients have died during the trials, however no compensation has been paid to the families left behind.

Internal hospital documents seen by Newsnight reveal that since 2005, 80 cases of severe adverse events in trials have been recorded in Indore. One patient listed on the severe adverse events document is Naresh Jatav, who is now four.

His father, Ashish Jatav, says that his son was a healthy three-day-old baby when doctors said he needed a polio vaccine.

Naresh Jatav - in the white shirt - with his family

The family says that they had no idea that the drug Naresh was given was a trial one, and that the hospital forms which they signed had been written in English "so we couldn't understand anything".

According to an investigation by the hospital, the healthy baby boy had a seizure shortly after receiving the drug and suffered an attack of bronchitis.

He now has breathing and eating problems, although the family have been assured that this is nothing to do with the trial vaccine. They say they no longer know what to believe.

Time after time in Indore, I heard a depressingly familiar tale of poor, often uneducated people saying how flattered and privileged they were made to feel as they were suddenly offered the chance to receive medicines usually out of their reach. All of them claim that, contrary to Indian laws governing drugs trials, there was no informed consent.

I also repeatedly heard patients' relatives say that the treatment they received at Maharaja Yeshwantrao Hospital was overseen by Dr Anil Bharani.

Dr Bharani has since been charged by the state government for receiving illegal payments and foreign trips from drug companies, and for carrying out drugs trials without patients' consent.

He refused to speak to Newsnight, even when I approached him in person in his office at the hospital. He called security and I was marched out of the hospital by an armed guard. But two days later, Dr Bharani was himself transferred from the hospital after more than 30 years' service.

Dr Bharani is just one of a number of doctors at the hospital who have been already been fined for irregularities during drugs trials. None of the problems might have ever come to light if it had not been for another doctor, Dr Anand Rai, who had an office on the same floor of the hospital.

Dr Rai says he was fired for raising concerns

Dr Rai says he became concerned when he saw poor people being ushered in to the best consulting rooms. He says he was sacked from his job because of his questioning, but that he has been researching the hospital trials ever since.

"They choose only poor people," he says, even though drug trial protocols demand that they should be carried out on all sections of society. "They chose poor, illiterate people who do not understand the meaning of clinical drug trials."

Dr KD Bhargava, head of the ethics committee at Maharaja Yeshwantrao Hospital, admits that the hospital's oversight of the trials has been flawed. "Suddenly lots of money got involved and there was too much going on. And, yes, maybe we may have lost control," he says.

But the issue goes well beyond one hospital.

Since India relaxed its laws governing drugs trials in 2005, foreign drug companies have been keen to take advantage of the country's pool of educated, English-speaking doctors and the huge population from which to choose trial subjects.

In the past seven years, nearly 2,000 trials have taken place in the country and the number of deaths increased from 288 in 2008 to 637 in 2009 to 668 in 2010, before falling to 438 deaths in 2011, the latest figures available.

The provincial capital of Madhya Pradesh is Bhopal - a city whose name will for ever be linked with the world's worst industrial accident. An explosion at the Union Carbide plant caused a gas leak that killed an estimated 25,000 people, campaigners say.

The only good thing to come out of the disaster was the Bhopal Memorial Hospital, built as part of a compensation agreement with Union Carbide to help care for some half a million locals affected by the disaster.

Little did they know that when they came for treatment, some would be used for clinical drug trials.

Ramadhar Shrivastav was one such person. As he makes his way uncertainly to the door of his house to greet me, he says he was lucky, having got off comparatively lightly in the 1984 disaster - only his sight was affected.

Five years ago, he suffered a heart attack and went to the Bhopal Memorial Hospital. He does not read English, and it was a journalist who last year noted that his discharge paper showed that he was part of a trial by the British company Astra Zeneca on a drug being tested for patients with ACS (acute coronary syndrome).

Mr Shrivastav claims the drug has affected him badly and he now cannot work.

Ramadhar Shrivastav had previously been caught up in the Bhopal leak

When he learned we were from Britain, he asked us to pass on a message to Astra Zeneca.

"Please don't do these trials on poor people. Rich people can overcome these problems but if I can't work, the whole family suffers. Why did they choose us? They should have tested it on themselves."

Astra Zeneca admit there were problems with consent with a few patients on the trial identified through there routine monitoring during the trial and the issues were quickly rectified. They say that Mr Shrivastav was not one of those affected.

From a medical point of view, doctors agree that the long-term effects of exposure to the Bhopal gas, methyl isocyanate, are still not known so why use the victims for drug trials? I put this question a doctor involved in setting up the Bhopal Memorial Hospital and who once served on the ethics committee there, Professor NP Mishra.

He says trials are carried out for the long-term benefit of patients. "It's not being tried out to harm them."

But haven't these people suffered enough? Is it right to put them at further risk in a clinical drug trial? "The way you talk, medicines would never be developed."

I ask again, why choose gas victims? "That I cannot comment on," he says. "It was not my job to find out."

The problem, I found while working on this subject, is finding anyone who is prepared to be held responsible.

I found Tarjun Prajapati supervising a construction site in a new suburb of Bhopal. He is joint owner of a building company. His father was a gas victim who, four years ago, suffered a heart attack. He was given drug called Fondaparinux at the Memorial Hospital. When he ran out of the medication, his son found it easier to nip out to the shops rather than cross town to pick up more from the hospital for his father.

"I went to the market to buy them but couldn't," he remembers. "I was told they were only available from the hospital and only then did I realise he was on a trial drug. I feel very bad that my dad died because of those medicines."

This claim is impossible to verify because, once again, there was no autopsy.

On the trial documents, it says that the British company Glaxo Smith Kline (GSK) are the sponsors of the drug, are responsible for the trial and are the investigators of the drug.

But GSK says they bought the rights to the drug while the trial was being carried out by the French company Sanofi, which is named as a collaborator on the document. When we contacted Sanofi, they told us the trial was in fact "conducted through an Indian research organisation called Quintiles".

Satnam Singh Bains, a British barrister in Indore, is looking into the complaints

There is no doubt that the drugs trial set-up can be complicated. A couple of drug companies might team up and then delegate the actual work of the trial to what in India are called Clinical Research Outsourcing Organisations. In the past, when there have charges of malpractice, drug companies have tended to blame these local companies.

Which leaves those who believe they have a just grievance against the drug companies somewhat bewildered.

Lawyers are now looking at whether there is a case to answer in the UK. Satnam Singh Bains, a British barrister in Indore, is looking into a couple of cases.

He shows me a recently published report by the Indian Parliamentary Committee on Health and Family Welfare that looks into what is happening around the country. The report is damning.

It confirms that the set-up for regulating trials in India is, in Mr Singh Bains' words, "not fit for purpose". There are too few inspectors at the regulatory agency, coping with too many demands, including having to supply data on 700 parliamentary questions and 150 court cases in one year.

"Still worse," the report says, "there is adequate documentary evidence to come to the conclusion that many opinions [during the drug trials] were actually written by the invisible hand of drug manufacturers and experts [the doctors] merely obliged by putting their signatures."

Mr Singh Bains says there are real concerns. "About, at the very least, collusion between experts and the drug manufacturers or, at worse, there is a suggestion that there is a fraud taking place - that these reports are being signed off without any independent, clinical scrutiny of their findings in the way that conclusions are expressed."

He adds that this could have global implications about "whether the findings of these clinical trials can be safely relied upon".

Sue Lloyd-Roberts reports from the poverty-stricken state of Madhya Pradesh