In Moscow, history is everywhere

- Published

As Russians remember the victims of the Stalinist purges, which reached fever pitch 75 years ago, a newly published database gives many Muscovites a chance to discover the chilling history on their doorstep.

As the long, bright days of Moscow's hot summer drew to a close this year, my family and I moved out of our much-loved, late-19th-Century flat. We moved across the city for boring, practical reasons, to be closer to my wife's new office. We left our beautiful, old home with heavy hearts.

Like many Moscow apartments, it did not look much from the outside - a heavy, grey-steel security door, a scruffy communal entrance hall, a grand old staircase with a cast-iron banister spoiled by multiple layers of shiny, off-blue institutional paint.

But stepping through the front door took you into another world - high ceilings, big bright windows and a sense of history - a third-floor home that would not look out of place in Paris.

It was in that kitchen that my artistic four-year-old daughter learned to paint. It was in that long corridor that her twin brother learned to take corners on his scooter at high speed. We all remember the old place fondly.

Like thousands of people in Moscow, I was curious this week to see if my home was on the new database, external, showing the addresses of those killed in the purges - a sea of tens of thousands of blood-red dots on the map of Moscow. As my new flat was built too recently, I searched under my old address.

Lyalin Pereulok - or Lyalin Lane - is a gently curving street barely 500 metres (540 yards) long.

Most of the buildings are low-rise and well over 100 years old. I found that, on this lane alone, 25 people were taken away to be shot - most of them in the bloodiest years of 1937 and 1938.

In my flat - Flat 7 at Number 9 - lived two brothers. Olimpiy Kvitkin was killed in 1937 and his younger brother Aristarch in 1939.

It turns out that Olimpiy Kvitkin was a rather important person. Born into an aristocratic and military family, he became a life-long socialist and revolutionary. After studying mathematics at the Sorbonne University in Paris, he became one of Stalin's leading statisticians. He was the man in charge of the 1937 census, an ambitious attempt to count everyone in the Soviet Union.

That was where his troubles began. Because Stalin had announced in 1934 that the population was 168 million and growing fast but, when the returns came in from the 1937 census, it was clear that the population was just 162 million - six million fewer than Stalin had announced just three years earlier.

It did not mean Stalin was wrong, though he might have been out of date. It meant that the sheer, unimaginable scale of the millions of deaths from the man-made famines of the 1930s was starting to show up in the official statistics. By far the largest numbers died in Ukraine, in what is known as the Holodomor - the extermination by hunger.

The results of Olimpiy Kvitkin's census were simply unpublishable. Within days of the first, still-secret findings being delivered to the Kremlin, he and three senior colleagues were arrested.

The Bolshevik journal claimed a "serpent's nest of traitors in the apparatus of Soviet statistics" had been crushed. Pravda said the men had "exerted themselves to diminish the numbers of the population of the USSR". Though the diminishing was, in fact, the fault of Josef Stalin's brutal policies.

Olimpiy Kvitkin was shot on 28 September 1937 and buried in a mass grave in the beautiful red-brick Donskoy cemetery in Moscow.

The importance of his census was only recognised when it emerged from the secret Soviet archives 52 years later, in 1989.

There is a postscript to this bloody tale. Despite the ghosts of the Kvitkin brothers and 23 others, Lyalin Pereulok is still a favoured street for Moscow's elite.

Sometimes, as I took my children to nursery school, I would see the security men of a Russian member of parliament.

He was Andrei Lugovoi, the former KGB man wanted by British police in connection with the killing of Alexander Litvinenko in London in 2006, with the lethally radioactive chemical Polonium 210.

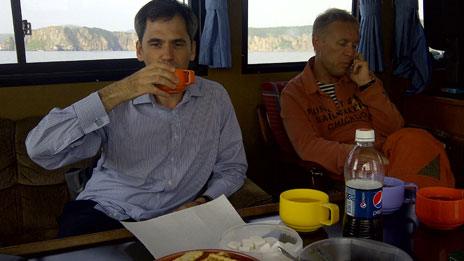

Daniel Sandford (left) having tea with Andrei Lugovoi

One day when interviewing him, I mentioned that I had seen him on my street.

"What number do you live at?" he asked.

"Number nine," I said.

"Ah," he said, "I live at number seven."

In Moscow you never can escape from history.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11.30am and some Thursdays at 11am.

Listen online or download the programme

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.