Africa's bright future

- Published

I have been working on Africa since the 1970s, and now, as I leave the BBC, I look at the continent of my birth and see a brighter future than at any time I can remember.

Johannesburg, June 1976. I was a student at university when the first reports came through of black school children clashing with police in Soweto. As the number of dead mounted we marched into town - only 50 or 60 of us at first, but joined by men and women, who poured out of offices and building sites. Within an hour we had thousands behind us.

The real clashes were in Soweto itself - miles from the calm streets of downtown Johannesburg. Back at the university residence, friends were being issued with army rifles. "Would you shoot me?" I asked. They didn't answer.

It is easy - looking back - to forget just how much has changed. Apartheid was still strong - very strong - back in the late 1970's. The Portuguese empire had only just collapsed. Zimbabwe was still Rhodesia. South Africans were fighting in bush wars all across the region. Friends were "up on the border" as they used to say, doing military service. It seemed that the killing would never end.

I left for London, working on Africa, first for the Labour Party and then the BBC. Decolonisation was still very much a live issue. Most of independent Africa was little more than a decade old. But already optimism was ebbing away.

Men like Congo's Mobutu Sese Sekou and Nigeria's Sani Abacha stripped their countries bare. There were dangerous buffoons like Uganda's Idi Amin and Bokassa of the ludicrous Central African Empire. We laughed, but they were killers. The shine had come off the brave hopes at independence.

But moving swiftly on, we find a new era at hand - and a much brighter outlook. The old deference for African leaders has been stripped away. The Organisation of African Unity is now the African Union - still weak, still shambolic, but struggling to reform itself.

It's a long hard road and its only just begun. But apartheid is over, colonialism is a memory and morale and optimism are on the rise. Africa has come a long way, in the last 36 years.

An idiotic war in Eritrea

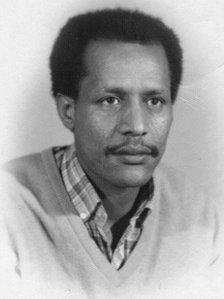

In the early 1980s a tall young man walked into the Labour Party office where I worked.

As Africa secretary, I got a lot of visitors. But somehow Ermias Debessai was different. He looked me in the eye and said: "You must come to Eritrea." I understood little enough about the Horn of Africa at the time, but I knew they had been at war with Ethiopia for 20 years.

"How can I?" I asked. "Just get to Port Sudan and we will take care of the rest," Ermias assured me.

And so I did. But Port Sudan is a good 250km from the Eritrean border. After a grinding 36-hour journey over a trackless semi-desert I reached the rebels' information centre. Over tea we discussed world affairs. The Eritreans were knowledgeable and spoke good English.

The BBC was required listening. When Focus on Africa came on, the aerials went up and there was a lull in the war.

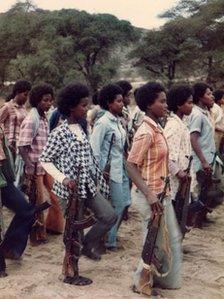

The EPLF was an extraordinary movement. From building hospitals, cut into the mountains, to using captured Ethiopian tanks, nothing daunted them.

I crouched in a trench above the town of Keren, watching Ethiopian soldiers on parade, as the shells exploded around us.

In 1991 the EPLF finally took the capital, Asmara. It's a beautiful art-deco city, with a charming people, happy to sit and sip coffee as the hours go by. My friend, Ermias, became ambassador to China. It seemed Eritrea would be a beacon of hope and progress across the region.

But an idiotic quarrel in 1998 over a tiny village on the Eritrean-Ethiopian border changed all that. It led to yet another war that cost least 100,000 lives. In the recriminations that followed, the constitution was scrapped. Democracy was put on hold. Journalists and politicians arrested. All freedoms eliminated.

And what of Ermias, my friend? He disappeared into the maze secret jails. I have no idea if he's alive - he probably isn't. Just one more life extinguished by a country that once held so much hope, by a regime that has stolen it.

The complex history of Marikana

Nothing has so shocked South Africans in recent years as what happened at Marikana. Miners marching down a hill confronted the police, who opened fire with automatic weapons. Men lay dead and dying in the dust.

A commission of enquiry is now searching for the causes - of which there were many. But among them must be the poverty of the miners themselves. Many live in the most basic of shacks - without water, electricity or sanitation.

Why is it that so many years after the African National Congress took power this is still the case? The answer lies - partly - in the peculiar history of the area.

The whites conquered the Bafokeng people during the 19th Century. The town of Rustenberg sprang up and, just to the north, the president of the Transvaal, Paul Kruger, bought a farm. It was from here that the great man plotted the defeat of Britain during the Boer war.

But, so the tale goes, Kruger got on rather well with the Bafokeng and told them that they could buy farms, just as he had. "Send your sons to the gold mines to earn cash," he said, and they did. They pooled their resources and bought back the land they had occupied for centuries.

Years later the world's richest deposit of platinum was discovered here. After many battles, the Bafokeng won the right to the royalties, transforming the fortune of their nation.

But there was one downside. Few of their own sons wanted to be miners, so it was to Zimbabwe, Mozambique and the Eastern Cape that the mining companies turned for labour.

Most miners lived in hostels - depressing, male-only accommodation - certainly not homes. Gradually their families set up camps nearby.

The Bafokeng were furious. This land - their treasured birthright - was being encroached on by ever-spreading squatter camps. They ordered that no facilities should be provided.

Now informal settlements, as they are politely known, can be well-run. Some even boast schools and clinics. But the camps around Rustenberg are amongst the most squalid I have ever witnessed - an unintended, but tragic consequence of the complex history of this corner of the country of my birth.

The organisations that never leave

Working on Africa since the 1970s, some things never seem to change. There are the presidential motorcades - blue lights flashing, scattering children and hawkers along their route. There are the marble floors of the five-star hotels - complete with sleazy businessmen of all nationalities and women of easy virtue. And there are the weapons sold by warlords and arms dealers, like Viktor Bout, who did so much to leave a trail of death across the continent.

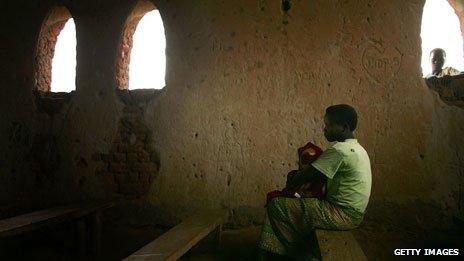

But there are other images that stick in my mind as well. The school, just north of the Congolese town of Bunia. The area had been stripped bare, as it changed hands between rebel groups. Only the church had managed to keep its tin roof.

But that was a few months ago and already the teachers, supported by the church, were back. A few books had been salvaged and they were giving instruction to 50 or 60 children, seated on the ground. In towns across the Congo you will find the Catholic Church doing what it can to pick up the pieces.

In the arid plains around Fik in the Ogaden region of Ethiopia, you will see the mosque playing much the same role - imams giving instruction to their pupils, the faithful offering charity to the poor.

It's not just the religious institutions. The United Nations is frequently derided for its air-conditioned offices and untaxed salaries. How often are they commended for staying on in South Sudan - even when the air hangs thick with insects and the sucking mud is up to their thighs?

And finally there are the charities. There are the water engineers of Oxfam, digging wells to save the lives of refugees. And the nurses and doctors of MSF, treating patients, while killers from the Lord's Resistance Army roam the dense forests all around them.

These are the organisations that do not go away. They might have to flee to the bush if the fighting gets too hot, but they will be back. Their interest and concern doesn't come in fits and starts. They will be with the people, long after the media circus has passed on, seldom to return.

Economic medicine, and the basis of growth

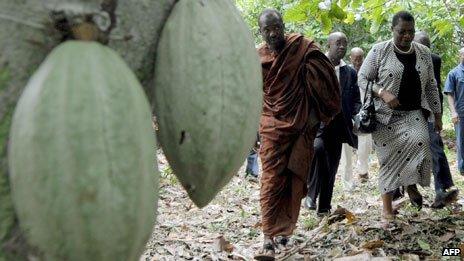

World Bank officials visit a test coca plantation in Ivory Coast (2008)

In the early 1970s I sat down to write an essay on an exciting development in African agriculture - the establishment of Ujamaa villages in Tanzania.

They were the vision of the country's legendary president, Julius Nyerere. As I remember, the aim was to bring scattered peasants together in at a centralised point. From here excellent state services could be provided, while collective farming would transform the lives of ordinary men and women.

The idea seemed flawless. My lecturers at the University of Cape Town were as enthusiastic as I was. I set about writing an essay on their merits. The first results had come in but - to my horror - they showed that production had fallen!

"How could this be?" I thought. "It must be a mistake."

As the years went by there were many times that I thought Africa's economies must be going in the wrong direction. Take the example of the structural adjustment programmes imposed by the IMF and World Bank. "How could they inflict such suffering?" I wondered. "Why are budgets being slashed, services dismantled - all sacrificed on the alter of economic dogmatism?"

But gradually I have been won round. The medicine prescribed by the international financial institutions may have been distasteful, but perhaps it has worked. Africa has been growing fast for the past decade. Was it the critics like myself who were wrong and the economic orthodoxy that was right?

It was when I visited Ghana a few years ago that I was finally convinced. I found myself in the glass and chrome office of the chief executive of a bank. I won't name him to spare his blushes. But he was truly remarkable. He'd given up an exceptionally well paid job in New York to come home. It hadn't been easy, but within a few years he had persuaded friends and family to back him, and his new bank was launched. Today it operates across West Africa.

"Of course I know all about the corruption and the nepotism," he told me.

"But I was born here. This is the place I know - and I can make money whatever they throw in my path."

Nor is he alone. Time and again I have come across young, ambitious men and women who are determined to succeed. Not for them the corridors of political power - rather the open road of the market, whatever the obstacles.

It's that kind of attitude that's transforming Africa. Sure there are plenty of examples of failure, but on the whole things are looking up. The old illusions I had from my student days are gone. But the prospects for Africa are brighter than at any time in my life.