A serious Justin at last

- Published

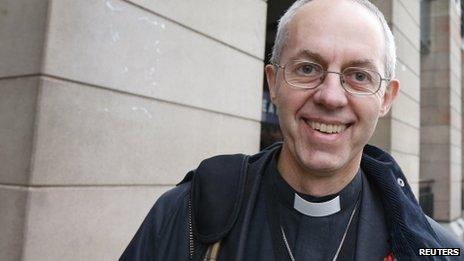

Justin Welby is expected to be named the next Archbishop of Canterbury on Friday. Will this help end the years of mockery experienced by other holders of his first name, asks Justin Parkinson.

Justin time. Justin case.

It is a forename given to appalling jokes.

Then there are the slips of the tongue. We've been called Jason, Julian, Joshua, even Tristan.

The Justins of this world have not had an easy time of it. We exist in the edges of people's nominal universe, forever meshed in with all the other, more common J-names.

Justin lacks the solid machismo that Matthews, Richards, Brians, Thomases and Stevens take for granted. Rather, it lurks among the Adrians and Gavins of this world.

Sure, there are a few famous Justins. Justin Timberlake, the singer and actor, is probably the best known. Or maybe the newer kid on the block, the teenyboppers' favourite, Justin Bieber.

There has been success for the frontman of the not-entirely serious rock band The Darkness, Justin Hawkins, not to mention the comedian Justin Lee Collins.

The nation's children are frequently thrilled and amused by a slapstick BBC show called Justin's House, in which entertainer Justin Fletcher and his sidekicks, Robert the Robot and Little Monster, get up to all sorts of adventures.

So there has been progress in getting the name out there, at least in the world of showbusiness. But for every step forward, there is a slide back into mockery.

Many will shudder to learn the American wrestler Peter Polaco sometimes adopts the alias Justin Credible.

Only someone not christened with the name could be so cruel.

Justin Welby has a name which is dwindling in popularity

But perhaps Polaco has inadvertently hit on the fundamental question - can the name Justin ever be truly credible?

The career of Justin King, chief executive of the supermarket giant Sainsbury's, would suggest it can be.

Yet reverse his name to see how far we have to go. King Justin? It doesn't roll, does it?

The presenter of BBC Radio 4's Today programme, Justin Webb, with his many years of serious reporting and consideration of the great issues of our time, is giving it a good go on the gravitas front.

Yet, where are all the senior politicians sharing the same forename? Along with Darrens, Waynes and Jordans, they are in short supply among the powerful.

So it is with great joy that many Justins, even beyond the Anglican Communion, have learned that one of our rank has risen to the heights of seriousness and respectability.

Justin Welby, the Bishop of Durham, is expected to be named on Friday as the new Archbishop of Canterbury.

The former oil industry worker joins his near-namesake Justus, who held the role in the early 7th Century, when the Church's missionary work in the north of England was still in its early stages.

Yes, if you go back a bit, you will see Justin is a name with a noble heritage.

Justinian I built the magnificent Haghia Sophia in Constantinople

It is an anglicised version of the Latin justus, meaning, as one might guess, "just", "fair", "equitable", "lawful", "proper". They are nice, if unspectacular, attributes for a ruler or a high priest to aspire to.

The Byzantine emperor Justinian is still known as "the Great" for reconquering Italy, north Africa and south-eastern Spain as well as codifying Roman law in a way which forms the basis of legal systems in many countries today.

Both his predecessor and successor were called Justin. The latter was a bit of a disaster.

Somewhere, somehow, the name lost its sense of importance and respect, one which befitted campaigners, warriors and wise leaders.

There have been some exceptions. The late Justin Fashanu is remembered for his bravery in becoming the first openly gay footballer during the 1980s.

But during my youth the best-known Justin was probably the Moody Blues singer and guitarist Justin Hayward.

Then there was the lugubrious-looking newspaper astrologist Justin Toper, who is still offering "live psychic readings" on the telephone.

One of the fictional Rats of Nimh was called Justin, a source of some embarrassment during English lessons.

There was little else for those of us whose parents, in the 1970s, thought they would choose a mildly exotic alternative to name their child.

Despite the recent rise of stars of light entertainment, Justin is not popular now.

In England and Wales last year, just 196 baby boys were named Justin, according to the Office for National Statistics, coming joint 244th with Martin.

Still besmirched by questionable wordplay and lacking their former popularity, the Justins are looking to Lambeth Palace with some excitement.

Will society be adjusting its views too?